30th Street Station District Plan unveiled to excitement and ambivalence

On Wednesday night the freshly unveiled draft of the 30th Street Station District was put before the the public, once again seeking input.

The North Concourse buzzed with excitement as Karl Bitter’s Spirit of Transportation watched attendees parsed over proposals to dramatically increase public space around the station, create a high density neighborhood on top of capped rail yards, and reopen an underground concourse linking 30th Street Station with SEPTA’s nearby subway and trolley station.

The plan, which envisions major station improvements and the construction of a new neighborhood, is being developed by Amtrak, Drexel University, Brandywine Realty Trust, SEPTA, PennDOT, the University of Pennsylvania, University City District, and others.

As the public scrutinized renderings and peppered the planning team with questions, a few wondered aloud whether any of it would actually happen. One attendee who declined to give her name asked a somewhat flummoxed Amtrak employee why she should believe, even for just one second, that SEPTA would reopen the commuter tunnel if the local transit agency didn’t have any representatives there?

Turns out, SEPTA’s officials were just running a little bit late. The skeptical woman ran off to catch a train before Byron Comati, SEPTA’s director of strategic planning, arrived moments later. That’s a shame, because she probably would have liked what Comati had to say about the tunnel.

“It’s something we are going to do,” said Comati. “SEPTA and Amtrak are currently looking at preliminary concepts.”

Comati listed a number of problems with the old tunnel, which was shuttered in the 1980s after an assault: sharp curves reduce sight lines, making the enclosure feel dangerous; new escalators and elevators are needed to make it wheelchair accessible, and; it’s prone to flooding right now, meaning leaks need to be found and fixed.

“Given all the small challenges, it amounts to one big challenge,” said Comati. “But it can be done.”

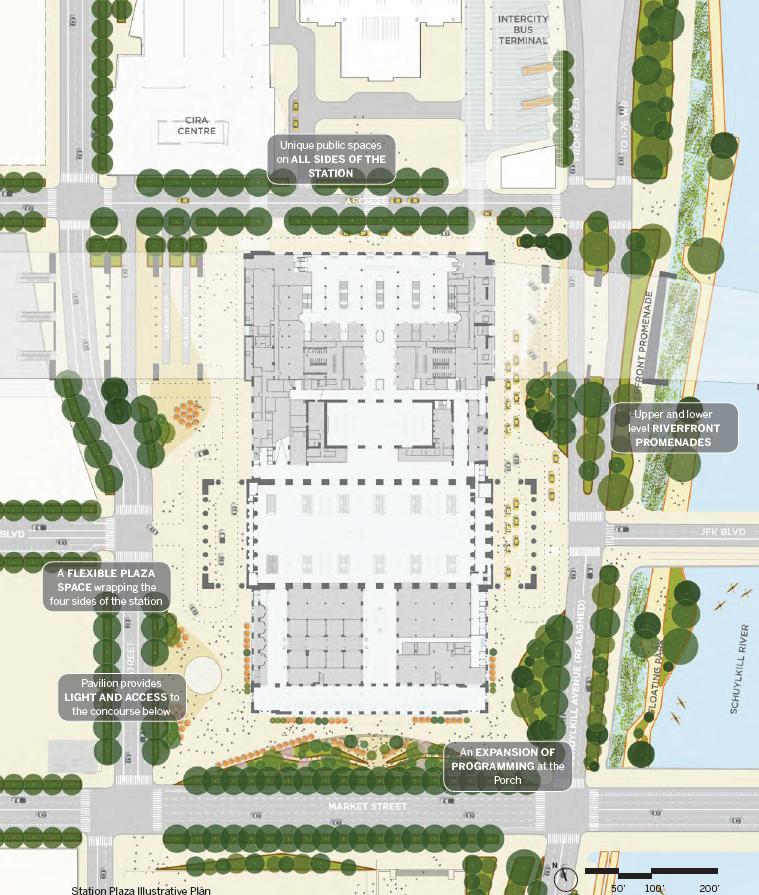

Reopening the connection between SEPTA’s station and the 30th Street Station is just one of many steps in the project’s initial phase, which focuses on improvements to the station itself and the immediately surrounding area. The draft plans call for new retail options inside the station, re-energizing the underutilized North Concourse, removing the small parking lots that encircle the station, and greatly expanding pedestrian plazas in the placemaking vein of The Porch.

Phase 1 includes building Schuylkill Yards, a proposed 14-acre, $3.5 billion innovation district just west of the station being developed by Drexel and Brandywine Realty. At its recent unveiling, officials promised to build Schuylkill Yards without adversely affecting the nearby communities. The district plan draft has Phase 1 wrapping up around 2030.

That’s when the district plan’s second phase would begin in earnest: the first rail yard coverings. Right now, the plan isn’t to cover all of the rail yard in a single step. Rather, sections of the rail yard will be capped over and then built upon over multiple phases and many years. The initial cap would be directly west of the Cira Centre; bridges over portions of the rail infrastructure that aren’t planned to be covered would extend Arch Street and the southern portion of 31st Street to help create a grid. That would wrap up sometime around 2040.

Following that phase, another cap would be built over the Amtrak lines and Schuylkill Expressway just north of the Cira Centre, extending to near the I-676 merger.

In subsequent phases, the coverings would expand, amoeba like, to blanket the remainder of the maintenance facilities and rail yards, culminating with an expanded Drexel Park over the uncapped SEPTA and Amtrak lines to connect Mantua to the new urban neighborhood and a new Schuylkill Bluffs park which would seemingly overlook the I-676/76 merger.

The timeline, like the plan itself, is far from set in stone. It’s barely written upon the strand, and—like so many past grand visions for this steely utilitarian space—shifting political and economic tides may wash it away. At the open house, planners emphasized that the capping order could very well change in the next 15 years before construction would begin.

PLANNERS TALK TO THE TALK, BUT WILL BUILDERS WALK THE WALK?

Most in the room agreed: the plan sounds great. Attendees said they appreciated how the plans evolved in response to public feedback. And nearby residents were particularly happy to hear promises to ensure that the ambitious economic development would benefit their communities.

“[The planners] have been listening to the community, [and] making changes,” said Chuck Bode, who lives in West Powelton. Bode praised the project’s openness to public feedback, and generally supports the draft’s designs. But Bode’s only cautiously optimistic.

“[The planners] tweak because of the [community] input,” said Bode. “The question is: When it goes to get built, do they follow this, or when the money shows up, does it go some different direction?”

Bode’s wife, Lucia Esther, chairs the West Powelton/Saunders Park Registred Community Organization. The West Powelton/Saunders Park RCO is one of nine community organizations represented in the project’s Civic Advisory Group, which meets regularly with planners to provide feedback. Esther worried about the impact the rail yard developments would have on her neighbors.

“We have many people whose parents were kicked out of the Black Bottom,” said Esther, referring to a largely black neighborhood that was bulldozed in the 1970s to make room for the University City Science Center and new buildings for Penn and Drexel. “They are seeing themselves being evicted again, as the second generation.”

Those were concerns echoed by Meg Lemieur. Lemieur lives in Port Richmond, but works for the People’s Emergency Center, a multi-faceted social services organization that also sits on the Civic Advisory Group. While saying the project’s backers “have done a really great job of talking to the community,” Lemieur still wondered whether Drexel and Brandywine’s promises to develop inclusively and equitably might go unfulfilled.

“It seems like they’re looking for some big names to go in there, and no affordable housing,” said Lemieur. “So I’m a little bit concerned that they’re creating a really elitist little neighborhood.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.