15 questions for behemoth U.S. Senate candidate John Fetterman

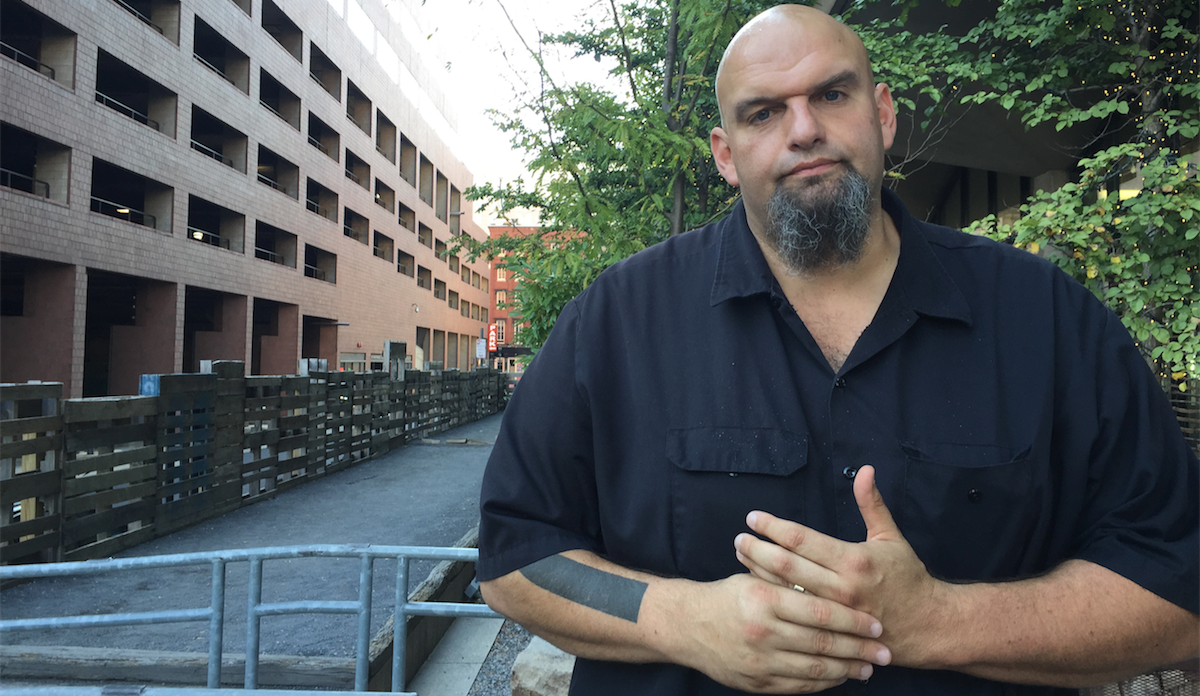

John Fetterman will return to Philadelphia tonight as his campaign for U.S. Senate continues to gain traction and/or widespread media attention. (Brian Hickey/WHYY)

It’s been one week since John Fetterman, the atypical mayor of Braddock, Pennsylvania, announced he was throwing his hefty hat into the field for U.S. Senate. He’s already drawn quite a bit of attention of both the local and national varieties.

The graduate of Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government enters a Democratic primary field featuring former Delaware County Congressman Joe Sestak and Katie McGinty, who until recently served as Gov. Tom Wolf’s chief of staff.

Should the 46-year-old candidate emerge from that field, he’ll face incumbent U.S. Sen. Pat Toomey.

On Tuesday night, the man who won his first mayoral election by a single provisional-ballot vote, and his wife Gisele, will held a meet-and-greet with supporters at Bob & Barbara’s (1509 South St.).

NewsWorks caught up with Fetterman at a beer garden in the shadows of Independence Hall last Thursday, a day after his local appearance was delayed because a young girl went missing in Braddock, a once-powerhouse municipality that’s gradually fighting its way back from rock bottom.

There, a 25-minute chat delved into the insistent you-don’t-look-like-a-politician narrative to how he’d serve Braddock, and Pennsylvania as a whole, should he win a seat in the U.S. Senate.

What follows is a lightly edited transcript of that conversation.

When stories are written about you, is the narrative always the fact that you don’t look like a typical politician?

It’s certainly not the narrative I lead with, but when you look like I do, it kind of slaps people in the face. There’s some advantage to it, too. We had to stop at a turnpike rest stop, and six or seven people recognized me. I wish it was for policy and some other things that I’ve done, but it’s like, ‘You’re that giant mayor from wherever.’

So, people do recognize me for that. If it helps, great. I always bring my wife with me, because I joke that she brings my average up, because I don’t have a lot to work with otherwise.

What were you like as a kid? Were you the big guy who protected kids from bullies?

I was actually pretty heavily bullied when I was super young. When I was in kindergarten and first grade, they used to bus the kids together, kindergarten to sixth grade, which was a bad idea. And I used to get the crap kicked out of me almost every other day. So, that really left quite an impression.

One of the great regrets of my life, actually, when I grew up and went into high school, I grew into myself and played football and everything. I never picked on anyone or bullied, but what I’m ashamed of is I didn’t stick up for, didn’t befriend, the marginalized, because I was a coward. I knew what that felt like, and I was afraid that, if I did that, I would be judged as a result.

I didn’t end up on this path until my second semester at business school when my best friend was killed in a car accident on his way to pick me up. That set off a chain of events that took me to Pittsburgh in 1995, and then that brought me to Harvard, and that brought me back to when I started in Braddock.

I was obsessed with this idea that you could get up in the morning, eat breakfast, kiss the people you love goodbye and have no idea that your life is measuring down to 20 minutes.

In a better search for meaning, I joined Big Brothers in New Haven [Connecticut] and I was paired with a little 8-year-old boy [who would lose both parents to HIV]. Did you ever see those old Benetton ads that featured victims of HIV and AIDS? That’s what [his mother] looked like: a skeleton with tissue-paper skin all over it. And that’s another thing I’m embarrassed about. I shook her hand, but what I was thinking was that I’ve never seen anything like that. At that point, I took him on and promised his mother I was going to do anything I could to get him to college.

I had never seen such disparity before. I was just blown away. He lived five or six blocks away from Yale University, one of the most prestigous universities in the world, and to have an AIDS orphan facing some almost Third World issues, I’d never seen anything like that. So I quit my job in risk management ,and I moved to Pittsburgh for Americorps. That’s kind of what started the chain.

You grew up where?

In was born in Reading Hospital, and we moved to York when I was five or six years old. South Central Pennsylvania, that’s part of the ‘red Alabama T.’ You grow up there and you have a very distinct outlook in life that I never really questioned until my world was turned upside down through those two major events.

I perceive an overwhelming sense of genuineness when I watch interviews with you. Is there stuff you aren’t showing?

I don’t know where that comes from. I like to think that’s because I don’t spin things. I don’t gussy up the memoirs. That’s exactly what happened: The good and the bad. I’ll share the stuff that I’m not proud of just as quickly as I share the stuff I am proud of.

I’m super embarrassed that I grew up largely privileged and insulated from a lot of the issues [I know about today]. I mean, we get residents’ heat turned back on in the winter; I never in a million years thought that I could come home from school one day and the lights or heat would be off. It’s embarrassing now to talk about it, but that’s how it was. I wouldn’t call it sheltered in that sense, but it certainly was not something I was preoccupied with.

I wasn’t curious enough as an undergrad. Played football for four years. Class president. I should have been more curious, but the truth is that I wasn’t. Life came and made some changes for me.

What do you make of the vapid nature of politics today? I don’t want to single out the Donald Trump effect, but that’s the freshest example of it, a circus show.

I was speaking earlier today, and I asked ‘What’s next? Where do you go from here?’ Now, candidates are actively insulting each other’s looks. Next, it’s going to be heads to the turnbuckles and rakes to the eyes. That’s really what it kind of is anymore.

People have confused politics and ideology with governance. Now that they have been permanently conflated, people don’t understand that it’s great to have ideas and have difference of opinions, but stuff has to get done. You have to make policies and society has to move forward. When that breaks down, you have the things that are happening in Washington today. That, to me, is the single biggest tragedy. That people have conflated who scores the most points with governance. That’s led to this intractable bitterness and resentment and tribalism.

You mentioned you’d rather talk about policies than the typical narrative that surrounds you. What would you like to talk about in that regard?

All I would like to talk about is this idea that there are a lot of places in this commonwealth, and all over, where the things that you get to take for granted, the things I took for granted growing up, are things that a lot of people can’t take for granted.

It’s not fair, as a 46-year-old guy, that I have two master’s degrees and zero student loan debt when there are people who can’t even attend community college or even dream of going to college. It’s not because I’m special, or exceptionally intelligent; it’s because of the random lottery of birth.

I was born into a family that could afford it. I was born into a family that valued education. I was born into a family with two parents, and it was assumed that you were going to go to college. That’s not fair.

We’re all different. We all have different plusses and minuses. But the playing field needs to be a heck of a lot more accessible, a heck of a lot more level, because we as a society are doing everyone a grave disservice. There’s something fundamentally and deeply wrong with that.

Is that too big to solve?

I don’t know, but I’m not going to be stopped by that idea.

One of the first things I said when I was elected was that Braddock will never be the same as it once was. I’m not going to be able to bring back the 14 furniture stores and three movie theaters and six banks we used to have. But what it can be is better, safer, more just, with your help.

I’m turned off by the cheesy rhetoric of campaigns, candidates saying ‘I’m going to go down there and teach those fat cats a lesson.’ No you’re not. That’s arrogance. It’s not all waiting on you. But what I can say is that I’m going to go down there and bring a work ethic, a level of understanding and pragmatism that I think is absent. And also, this notion that governance must be separated from the professional-wrestling aspect that I think defines modern politics.

It’s striking to hear that from someone who looks like they could fit in in the ring.

I have a story about that too. Pittsburgh has a lot of television shows and movies filming there. And I was actually a stand-in for the Big Show. I have a picture of that. He’s not actually as big as he says he is, but he’s a super-nice guy. … I wasn’t in it, but my friend was a commando who was killed by Bane in [“The Dark Knight Rises.”]

Will you be leaving Braddock?

Never. Never.

Well, are there things you would be leaving undone should you get elected to the U.S. Senate?

Of course. Of course there are things I’d be leaving undone. There’s a sense of responsibility for everything. I wish I could bring back the 14 furniture stores.

How were there 14 furniture stores?

That’s the amazing thing. It was ridiculous. Don’t take my word for it. Look at the business directories from back then. Braddock was one of the main shopping districts outside of Pittsburgh in the entire region. Braddock was Silicon Valley back then. It really was. How can this be? How can something that looks like this, is this poor, been a place where [Andrew Carnegie] the richest man in the world got his start? It’s unimaginable. It’s unimaginable, the decline, too. Can you imagine going to San Francisco 100 years from now and seeing a city that’s lost it’s s—? But that’s what happened.

It must have felt like an apocalypse, the end of the world, when all the mills started [closing]. Half the world’s steel came from there. And now, the mill in my community is the last steel mill in the Pittsburgh area. That’d be like the last brewery in Milwaukee.

The last casino in Atlantic City.

Something that defined the city. Yep.

I think it was a story on the CBS Sunday Morning show where I saw a critical city councilman …

Yeah. Jesse Brown.

Is an outsider/do-gooder coming in and drawing attention to themselves a common theme of your detractors, or was he more of an outlier?

Well, he’s certainly an outlier now. Spends his days watching a lot of ‘Wheel of Fortune.’ We took over Council. Now we have a great progressive council now that works with me, and gets things done.

But he definitely represents that old guard that, no matter what I do, he was going to oppose that. It kind of reminded me on a much, much smaller scale of when Barack Obama took office and Republicans were committed to his failure and no matter what he did, said or wanted to do, they would have been, ‘Nope, that’s not happening.’ That’s definitely the way it first started. But I realized that early on and said, ‘I don’t care what you say or do, we’re moving forward.’ I never spent a lot of time trying to win him over, because it was never going to happen.

How do you spread this message in the Phillys, the Readings of the world?

Those are the kinds of places where the message will really resonate. The core question I’m going to be asking, and I know my competitors will be asking, is ‘Where do you live? Do you think I would have a better idea of what your daily life is like, and the challenges you’re facing, or are these other people more in tune with the issues that you face?’

Whoever gets the most answers in the affirmative is going to be the next nominee.

Was there a moment you decided you were going to run for Senate, or was it more of a gradual thing?

It was actually very gradual. I was thinking that all these things are important to me, and I felt like I was bumping up against the limits of my office. With this desire to want to have a bigger impact across the political spectrum, I decided to shoot out a tester email to a good friend I’ve worked on a lot of campaigns with a couple of months ago. … I said, ‘Look, I’ll be very honest. I’ve been trying to drown this thing in the bathtub. Talk me out of this.’ The exact opposite happened, and it just evolved from there.

I was following the race very closely, watching the moves Mr. Sestak made, and [Allentown] Mayor [Ed] Pawlowski, and his entry and exit and the direction that, sadly, his career seems to have taken. There’s a real vacuum, and that’s why I decided to step up.

Looking back, were you always on a path that bent toward this political life that’s about to ramp up?

I never saw myself on a path to politics. I still don’t see myself as a politician, and I don’t mean that as a canned line to throw out there. I see myself as a facilitator and a social worker at the end of the day. I just happen to occupy political office. It’s just a vehicle to air, and work on, and promote some of the issues I find really important.

Are you looking forward to, or dreading, the rigors of a statewide run? With three young children, it’ll be tough.

I’m looking forward to the debate, looking forward to gettting into it. The two things that concern me: Not being able to see my family; I live for my wife and kids. I have a 6-year-old son, a 4-year-old daughter and an 18-month-old holy terror that my wife just had to wheel out of here and hopefully she could sleep. [Ed. note: When I arrived for the interview, Gisele was changing that holy terror’s diaper.]

And then, it’s inevitable that I won’t be able to focus on the town as much as I normally would. My phone’s still going to ring at 2 in the morning whether I’m campaigning or not. That’s the greatest fear of my life, outside of something happening to my family, is that phone rings at 2 a.m.

If I ever leave politics saying I want to spend more time with my family, I’m actually telling the truth. We’ve stereotyped that by, whenever we hear it, you think a scandal’s coming, you’re no longer viable. But that’s my idea of heaven.

If my job has any perks, it’s that I get to work from home and see more of them. A lot of working families, people are working two jobs. But that’s the one great joy of my life: Spending time with them. I think that’ll be one of the greatest challenges [of being out on the campaign trail] so I’ll try to bring them along as much as I can.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.