Where can the U.S. put 88,000 tons of nuclear waste?

While the U.S. struggles to build long-term storage for nuclear waste, other countries like Sweden, Finland, and Canada move forward with plans for geologic repositories.

Listen 10:51

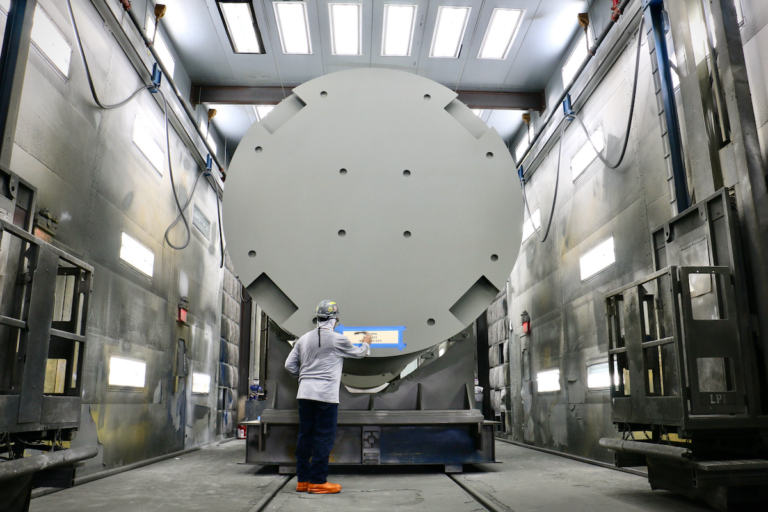

A worker stencils the destination on to fuel storage module at Holtec International in Camden. This one is headed for D.C. Cook Nuclear Plant in Michigan. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

As Sweden, Finland, and Canada move forward with plans to store nuclear waste in the long term, experts say the U.S. has “fallen to the back of the pack” and needs decades to catch up.

Nuclear power plants use nuclear fuel to generate electricity by a fission reaction, which involves atoms splitting. After a few years, the fuel cannot sustain the reaction anymore, and becomes spent. The spent fuel is still highly radioactive. The U.S. has 88,000 metric tons of spent fuel in nuclear power plants in around 30 states and adds 2,000 tons each year.

Right now, U.S. nuclear power plants store the spent fuel in giant concrete cylinders that are more than 10 feet tall with layers of concrete and stainless steel several inches thick.

These concrete cylinders, which are also called overpacks, are very safe, said nuclear engineer Joy Russell, the chief commercial officer for Holtec International, a leading manufacturer.

“We have modeled a 767 aircraft and also an F 16 aircraft crashing into an array of the overpacks. And there is no release of radioactive material … even under an event of such force.”

At a Holtec factory in Camden, N.J., workers check for defects in the containers with multiple tests, including putting them through an X-ray machine.

But despite all the tests, geologist Allison Macfarlane, says they will eventually leak and break down. Macfarlane, who used to chair the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, is now director of the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs at the University of British Columbia in Canada.

“We suspect they’ll last for decades. We don’t know how many decades. We don’t think they’ll last for hundreds of years,” Macfarlane said. “So, this is not a long term solution.”

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission licenses the cylinders for up to 40 years, though Holtec said they can last longer. But regardless, the spent nuclear fuel will remain a problem, said Macfarlane.

“People have thought of a variety of crazy schemes for dealing with nuclear waste, things like shooting it into outer space or whatnot. But we aren’t very good at getting rockets up without them blowing up.”

The best plan that scientists have come up with is to make a deep geologic repository — putting the waste deep, 400-500 meters below the earth so it remains away from humans and the environment for the hundreds of thousands of years during which it remains radioactive.

A repository would have to be far from earthquakes, volcanoes, or moving water. The layers of steel and concrete and soil and rock would contain the radiation. Fortunately, the U.S. has quite a few places like that, Macfarlane said.

“That’s not what should worry us. What should worry us, and what has been the sticking point up to now, is the societal political piece.”

States are not clamoring to be the home of a giant underground hole for nuclear waste. The U.S. government has been slow to act on the need to build such a repository, despite knowing about it for decades.

Subscribe to The Pulse

Money doesn’t seem to be the obstacle in this case: For years, companies that run nuclear power plants paid the government a fee specifically to cover the cost of a long-term waste repository. But the U.S. government later treated it like tax revenue and used the money to pay for other things.

Congress passed a law in 1987, put decades of work and billions of dollars to set up Yucca Mountain, Nevada to become a geologic repository. That did not go over well with people in Nevada or their representatives in Congress. They called the law the “screw Nevada bill.” The effort stopped in 2009.

It can be hard to get lawmakers to address this issue, said Rod Ewing, who has talked to people in Congress about this for years. He’s a professor of geological sciences at Stanford University and used to chair the Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board.

“It would be common for someone to say, ‘Well, thanks for all this work, but how is this going to impact my budget? I don’t want to read the whole thing, but could you just put yellow tabs where this idea is going to impact my budget or a criticism that might end up in the newspapers.”

While the U.S. struggles to build a long-term storage site for nuclear waste, other countries have succeeded. Sweden, where nuclear power is a major source of electricity, picked a site for a repository last year. It was not easy, and it took more than 20 years, said Saida Engström. She used to work for the Swedish company dedicated to managing the country’s nuclear waste.

“I had some bad days when I had people shouting … 4 centimeters from my face, ” she said. “I had to go to debates and people would say half-truths or whole lies.”

She said it worked out because: Sweden has a dedicated organization dealing with nuclear waste; they get specific government funding; they only consider places that wanted to have a geologic repository, and these places could back out at any time.

She and her team went around the country for years to talk to people in large meetings, and at their homes, to make sure they could talk to people who cannot make it to large public meetings.

She said ultimately, she would explain it to people like this: “if we do not find a place for this waste in the long term, we cannot do anything with it. We cannot export it, we cannot sublimate it, it will stay for our children and grandchildren.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.