Turn on your love light

Listen

(Image courtesy of Lutron Electronics)

The history, science and sex of the dimmer switch

When your mom is a knockout, this undoubtedly affects the path your life takes.

“He was always very aware of aesthetics because his mother was a model in New York City,” says Susan Hakkarainen, one of Joel Spira’s daughters.

Spira was family to not only lookers, but also successful, driven people. His father frequented speakeasies before gaining a seat on the New York State Liquor Authority. His father-in-law, J.I. Rodale, started an electronics company, then a giant magazine publishing business.

“His sister ended up going into the art world, and became the number two at the Guggenheim. So there has always been this right brain, left brain–the arts and the sciences–in our family. Very bauhaus,” says Hakkarainen, who, following in the family tradition, holds a PhD in Applied Plasma Physics from MIT, and is involved with several arts organizations.

Spira served in the Navy during World War II, where he worked on radar systems. Then, he earned a physics degree before moving to New York City.

It was there, in his Manhattan apartment, in 1959, where Spira’s tinkering would result in the device that forever changed the way humans see each other.

It was a new type of solid-state transistor that dramatically shrunk the hardware required to lower the lights: the dimmer switch.

Before his invention, there were dimmers in use in ballrooms and on Broadway, as well as in engineering applications, but the devices were primitive, large units often hidden in back rooms, where they emitted a great deal of heat.

Spira’s advancement was small enough and safe enough to slip into electrical boxes in the wall. It works by regulating the bursts of power that reach the bulb.

“You can turn on and shut off something very, very fast. It is almost like an extreme flickering of a light,” says Brent Protzman, an engineer at Lutron Electronics, the company Spira would form in the early 1960s.

“And if you turn it on and off fast enough, our eyes kind of aggregate that light, and it is actually less light, and that is really all that is happening. It is basically a super fast light switch that makes it feel like the light is at a much lower intensity.”

Mother’s little helper

In the early days, Lutron (which remains based in Coopersburg, Pennsylvania, outside of Allentown) didn’t market the dimmer to electricians or contractors. Instead, it wanted to appeal to a different audience: to women, including those interested in generating a little extra spice at home. Picture Betty Draper, bored in the suburbs.

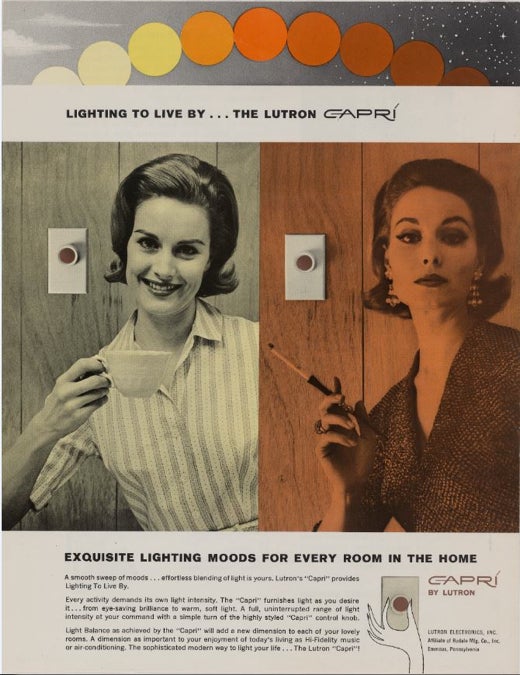

The company called its early dimmer the Capri. Susan Hakkarainen says her father considered every detail of the ad campaign, right down to the packaging.

“He was looking for a box that was attractive, and he found that a company did an overrun of perfume boxes,” she says. “He said, you know what, I’ll take these off your hands, and just print my name on it, and these were beautiful boxes, when everyone else was doing industrial boxes.”

Spira set up displays in New York department stores including E.J. Korvettes, so women could experience the dial for themselves. A side-by-side promotional photo showed a stay-at home mom sipping coffee under bright lights. But when they get dimmed, out comes a domestic goddess, a generous helping of decolletage on display, her face softly burning with desire.

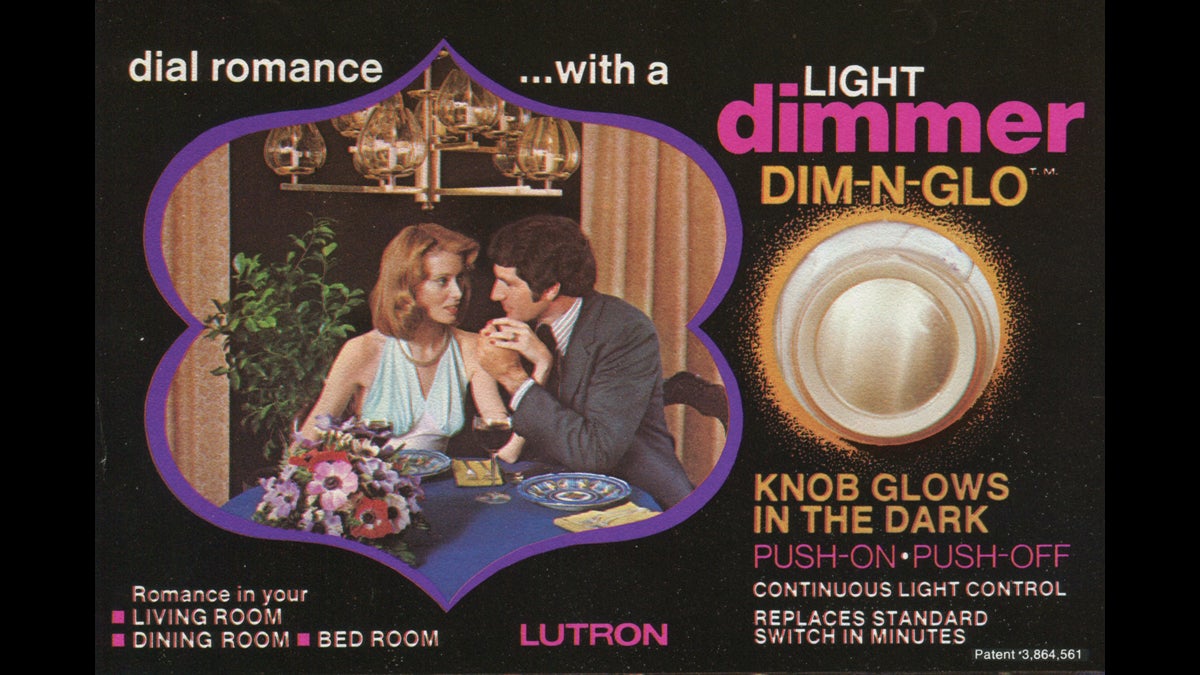

A print ad for the Lutron Capri. (Image courtesy of Lutron Electronics)

A print ad for the Lutron Capri. (Image courtesy of Lutron Electronics)

“The theme in the early days was ‘dial romance,'” says Michael Pessina, President of Lutron.

The Don Draper-style campaign was built around the idea that kids could still do their homework after school at the dining room table. Then, once they were safely tucked in, the adults could ponder making more kids at the turn of a knob.

“Because there’s nothing more romantic than that beautiful flicker of a candlelight, and the dimming technology could allow that to happen. So, any light, for any need or use of the space, and the dining room was a nice place for that,” says Pessina.

The dimmer soon expanded beyond the dining room and into the living room and eventually the bedroom. It gave these spaces access to the secrets of Hollywood lighting designers.

“If you do the lighting well, the shadows on your face are interesting and dynamic, so as you move, you watch each other’s faces, and you look attractive,” says Hakkarainen.

The soft light softens hard edges, the wayward hairs, the bags under our eyes. It seemingly glances off surfaces, rather than spotlighting them.

But does it actually kick start your libido in a more primal way?

“I think it is excellent marketing, but I’m afraid I can’t cite the science behind it,” says George Brainard, a professor at Thomas Jefferson University, where he researches light’s impact on humans.

While there’s no clear evidence the dimmer switch has the same impact as a little blue or little pink pill on our sex drive, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t influence behavior.

“We know for a fact,” says Brainard, “when you dim the light in the evening, you hasten the onset of the production of the hormone melatonin. That’s related to calming the body down, preparing it for sleep. And of course, romance is something we often do around the time of sleep. So you are gearing down from the heavy work day, slowing the pace, and perhaps getting in the mood.”

A green tint

In its 50-plus years on the market, the dimmer switch has evolved into something far more than a romantic tool.

“The dimmer has found a whole bunch of new uses, but primary among them, is the saving of energy,” says Bill Braham, an architect and professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

Less light uses less electricity, and lower light helps light bulbs last longer. Joel Spira and Lutron understood this from the beginning, and now the company, along with other dimmer manufacturers, market this angle, along with the aesthetic one.

Big buildings–think airports and skyscrapers–use dimmers to cut costs, and lots of modern offices strategically dim lights at certain times.

“If it is being done well, it is being dimmed in response to the amount of daylight available, to keep the amount of light constant, to save energy, all of which is still in the service of making you work as hard as you can for as many hours as you can, which I would describe as the opposite of what you do when you come home, or what you want to do when you come home,” says Braham.

Lutron now sells thousands of other products, including electronic window shades and other energy conscious devices. And while Joel Spira is named on hundreds of patents, it will be the dimmer switch that he’s forever linked. In 2010, the original was added to the electricity collection at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

“I knew him almost 39 years, and I rarely heard him at a loss for words,” says Michael Pessina. “But I remember we were standing there before the case was unveiled where the product was. I leaned over, and I said, ‘Chief, this is a pretty big deal,’ and he said, ‘this is about everybody, this is about everybody.’

“And as they took the shroud off the case, there was one of Alexander Graham Bell’s original telegraphs, there was a Thomas Edison light bulb, and there was Joel Spira’s light dimmer, first notebook, and original prototype. And I looked at him, and he couldn’t say a word. I just said, it is a big deal. And he just shook his head.”

Joel Spira was still the face of the company when he passed away in April of this year at the age of 88. He’s survived by his wife of six decades, Ruth, and their three daughters.

The first line of his obituary in the New York Times said he was a man who “changed the ambiance of homes around the world and encouraged romantic seductions of all types.”

“He would have been tickled pink with that,” says Susan Hakkarainen. “Because I’ll tell you, their code names for each other, which has never been told publicly, is Big Ben and Ruby Begonia. They were old time movie references, but they would sign birthday cards to each other, and Valentine cards…so they were always romantic, and we would always get from my father, all of us daughters, we would always get chocolates on Valentine’s Day from ‘your secret admirer.'”

Chocolates, love notes, nicknames. This guy was smooth, and with his invention, the rest of us could feel a little smoother, too.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.