The art of explaining science… and why it’s so hard to do

Listen-

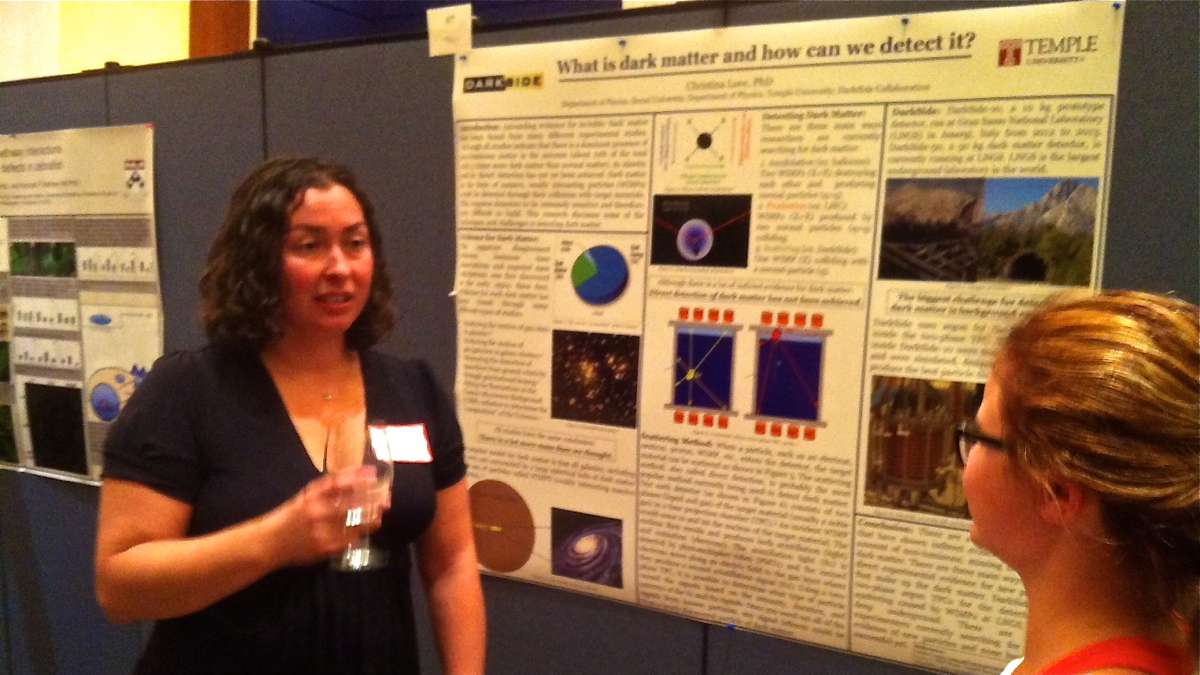

Christina Love

-

-

-

What makes a scientist a good communicator? It turns out the scientific community has become more interested in figuring that out.

Explaining science is something reporters, especially science reporters, must do. But most of us are not scientists. Instead, we rely on the type of scientist who is good at telling stories, good at translating what happens in the lab to people who may not have been around an Erlenmeyer flask since high school. So what makes a scientist a good communicator? It turns out the scientific community has become more interested in figuring that out.

Take a look at a definition of radiative forcing. I found this in a report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC):

“…the change in net irradiance at the tropopause after allowing for stratospheric temperatures to readjust to radiative equilibrium…”

Are you following? Me neither.

What about this?

The sun shines down on Earth, warming our oceans, burning our skin, heating the asphalt. The numbers suggest more and more heat is getting absorbed by the earth and its inhabitants, and less is being reflected out into space. This is making the earth hotter.

Now you know I’m describing global warming. Scientists face a struggle all the time – how to talk about their work in a way that everyone gets, but remains true to the science. And how not to wince the next day when the headlines miss the nuances in what they tried to say.

Twenty-nine year old Christina Love teaches physics at Drexel University. During her years of science education, she got no formal training in how to communicate with non-scientists. And that’s not unusual. When she speaks to biologists, she says she often has no idea what they’re talking about. That’s one of science’s dirty little secrets. A scientist out of their field, often knows just about as much as someone who majored in philosophy. So Love set out to organize what she calls “Start Talking Science.”

At an event at the Chemical Heritage Foundation in Center City, Philadelphia, Love stands by a poster explaining her PhD thesis on building a better machine to detect dark matter to a few young students. One is majoring in political science. And Love is giving some background.

“So you see these beautiful pictures of our galaxy,” Love tells a crowd gathered around her poster, “one model shows that our galaxy’s way deep down in this huge spherical halo of dark matter. We’re surrounded by it. It’s here but you can’t detect it.”

What is dark matter?

“Dark matter is this large amount of mass that we detect based on the gravitational effects,” says Love. “So essentially we know that there’s a lot more mass than we see. Detectors that have to be very very sensitive to detect something no one can see or feel.”

Get-togethers like this are something scientists do all the time with other scientists. But this time, this event is open to the public, and scientific jargon is discouraged.”

“When I first learned about dark matter, I was an undergrad at West Chester University, and I really wanted to scream,” says Love. “I thought how is this possible, how did I not know this up until now. I went through my grade school and high school thinking we know everything and it turns out what we know is less than five percent of the entire universe, so there’s just some amazing things out there that everyone deserves to know and understand.”

The push to communicate

In the last 10 years, major scientific societies have begun holding workshops on communications. Some have even established big money prizes to promote the idea.

Naomi Oreskes teaches the history of science at Harvard University and she’s written extensively about funding for climate change deniers.

“There’s definitely been a change from a feeling ten years ago that it was the job of the scientist to do the science as well and as accurately as possible,” says Oreskes. “But it was someone else’s job to communicate it. And most scientists that I knew and I talked to thought it was your job, it was the job of science journalists. And scientists used to get mad because they thought science journalists did a poor job.”

After writing extensively on climate change, Oreskes has turned to “science-based fiction” to reach a new audience. Her latest book “The Collapse of Western Civilization: A View From the Future,” is a worst-case climate change scenario looking back from the year 2393.

Oreskes says controversies around politically charged topics such as climate change have led a lot of scientists to rethink how they talk about their work. If the science is complicated, she says, it’s a delicate art to simplify without dumbing it down.

“I always like to say it’s not dumbing it down; it’s cleaning it up,” says Oreskes. “But how to make that cleaned up, how to present it in a way that’s not misleading, it’s not trivial.

The pushback on communication

Oreskes says one of the best science communicators to emerge from the lab into the public sphere is Penn State climate scientist Michael Mann. Mann has had his own turnaround when it comes to speaking out.

“We have to accept that we don’t live in a world where scientists can simply do the science, publish it and assume it will translate into good public policy,” says Mann. “It doesn’t work that way.”

If Mann sounds like he’s on the warpath for better science communication, he is.

“We have to be out there defending the science, explaining the science and its implications because if we don’t, it means special interests, front groups, paid attack dogs will simply poison the discussion with misinformation and disinformation.”

Mann’s views are shaped by personal experience. In 1998 he co-authored a paper that looked at weather patterns from medieval times by analyzing ice cores and tree rings. And in this paper was a simple little graph, one he thought was pretty uninteresting.

But the graph communicated his findings so well, so easily, to a lay audience, that it got a lot of press. Then, he became a top target for those who claim climate change is a hoax, including powerful interests in the fossil fuel industry.

He was called before Congress; his emails were hacked. At one point, in a national magazine, he was referred to as the “Jerry Sandusky of climate change.”

“I never imagined that majoring in physics and applied math and going into the study of the climate system would place me in the center of what may be the most contentious debate that we have faced as a society,” says Mann. “I didn’t sign up for that.”

But now Mann has embraced it. That iconic chart is now known as the hockey stick graph. It shows how the average temperature of the earth has risen dramatically since the start of the industrial revolution. He’s even written a book on his experiences. “The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars: Dispatches from the Front Lines.”

Mann says back before the famous graph, he was pretty naïve and just wanted to stay in his lab doing nerdy calculations. He’s now an advocate for scientists to get out of their bunkers and engage the public.

“And part of that is using metaphors and trying to get outside of your own scientific comprehension of the issues,” he says. “And thinking about how would I think about this if I wasn’t a climate scientist? If I wasn’t a scientist at all.”

Communicating the scientific process

Mann says the challenges include widespread misconceptions about the scientific process.

“We don’t prove things in science,” says Mann. “We establish best explanations for observed phenomenon. We apply weights of evidence. We pose hypotheses and then we look at observations and see if they support the hypothesis. It’s an iterative process. There are huge uncertainties at the base of every area of science; that doesn’t mean that we know nothing.”

Mann and Oreskes, the Harvard professor, agree that the problem for scientists is not just a lack of skill or comfort with public speaking. Science sits at the center of many major public policy debates. Economic interests on both sides look for science that supports their position – and will attack findings that don’t.

That point is not lost on younger scientists like physicist Christina Love.

“It’s almost a fear of not explaining it properly and all of a sudden becoming the next controversy,” she says. “And so you kind of see that with evolution and climate change and at the risk of getting cosmologists in trouble, I don’t think the Big Bang theory is attacked all that much, and I don’t really understand why.”

Maybe the explanation is that, even though some think the Big Bang conflicts with the Bible, the theory doesn’t really threaten anyone’s livelihood. Yet.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.