Pus, grenades and Ben Franklin: America’s first great vaccine debates

ListenThe founding father’s very real stake in the colonial war over inoculation.

If you think the public debate over vaccines is a modern one, think again. It actually dates back to the colonization of North America, when the very concept of immunization was just taking shape.

And the arguments were as heated then as they are now, involving name calling and in at least one instance, an act of violence.

Caught in the middle of the crossfire was one of Philadelphia’s most noted figures, Benjamin Franklin. During a high stakes time when the free press and scientific thought were just emerging, Franklin literally printed the paper credited with fueling the main opposition to innoculation—the precursor to vaccination. But within a decade, he turned into an outspoken advocate.

A terrifying disease

Franklin was born in Boston, during a time when smallpox was a fact of life.

“It was every bit as much of the American experience as the Revolutionary War or the Tea Party or what have you,” says Dr. Howard Markel, a pediatrician and medical historian at the University of Michigan.

And it was terrifying, with black blisters blanketing a person’s body inside and out. The disease killed 25 to 30 percent of those infected, and it was terribly contagious, even after a person died.

And on top of those scary statistics, nobody knew how it spread.

“It just seemed to come above,” says Markel. “Don’t forget, nobody knew about microbes or microbiology or the germ theory of disease.”

One of the worst outbreaks hit Boston in 1721, via an infected sailor, spreading to nearly half the city.

Searching for a response, the prominent puritan minister, Cotton Mather, rose up as “the first really strong proponent of inoculation,” explains Cristobal Silva, professor of early American history at Columbia University.

A precursor to the vaccine, inoculation aimed to give a person a weaker form of smallpox, producing an immunity to the stronger, far deadlier disease.

Inoculation had been in Asia and Africa for a long time, but it was brand new to America. Mather learned about it from reading science journals from Europe, which was then breaking into the Enlightenment, as well as directly from his servant, Onesimus.

Unlike many around him, Onesimus and other slaves weren’t getting sick because they’d been inoculated before arriving to the colonies, says Silva.

Inoculation essentially involved soaking a thread in the pus of an infected blister. After letting it dry and covering it for several months, one would then place that thread in the open wound of a non infected individual and let the disease take its course.

“It’s incredibly gross and yet if you think about it, one out of three or four people died [of smallpox], it was your best chance to avoid getting that terrible disease.”

The practice came with risks. Some people got very sick and died.

Paper wars

Mather teamed up with a Boston doctor, inoculating his family and congregation. Backed by the main Puritan authorities, he promoted the practice in the official newspapers of the time, the Boston Newsletter and the Boston Gazette.

But inoculation faced popular resistance, and the debates quickly heated up.

The anti-inoculators found their voice in a new paper, the New England Courant, which became instrumental in fueling the debate and those looking to challenge authority.

“They’re producing what we now look at as being the first independent voiced newspaper in New England,” explains LaSalle University historian George Boudreau.

James Franklin owned the press and paper, and the young man tasked with setting text and actually printing it was his younger brother, Benjamin. At the age of 15, Ben Franklin was a buff, bright and aspiring writer. He wanted a voice in the paper, but his brother would have none of it, according to Boudreau.

Opponents pointed to the risks of the procedure, accused Mather of violating the Sixth Commandment and the hipocratic oath, “Thou shall do no harm.” Others accused Mather of playing God, interfering with a greater plan in deciding who should get sick and who shouldn’t.

A main ringleader of anti-inoculators, Dr. William Douglas, accused Mather of being a quack, writing in 1721: “How can we suppose a man of a vocation which requires all his time conscientiously to discharge of the same, should pretend of a business of so great an extent?”

The debate had nuances. Even some anti-inoculators backed inoculating slaves to increase their value, while others supported the idea but thought the way it was being practiced was careless and harmful.

But the debate quickly devolved into name calling and a sort of “tit for tat,” says Silva.

It took an even more serious tone on November 1721, when someone threw a grenade into Mather’s home, with a note wrapped around it that read: “You dog, and damn you, I will inoculate you with this, with a pox to you.”

Luckily for Mather, the grenade didn’t go off.

Mather argued that inoculation was the merciful, great work of God, likening the anti-inoculators to the epidemic itself and having “a very satanic furry acting them,” says Boudreau, in reference to a 1721 passage from Mather.

Historians like Boudreau and Silva don’t know what young Ben Franklin actually thought of inoculation at that time, but he was certainly no public advocate.

Printing a paper does not mean one endorses all of its views, Markel points out. The two brothers also fought, and some argue James physically abused his brother.

Ben Franklin does sneak his way into the paper, anonymously. He submits letters, many of which were widely believed to be poking fun at Cotton Mather, under the pseudonym of a widow, Mrs. Dogood.

From apparent bystander to ‘vehement’ advocate

Ben Franklin’s own views on inoculation don’t surface until several years later, in the 1730s, once he has gained prominence in Philadelphia, building his own printing empire.

By then Franklin is running a successful press out of his home (which would have been at 139 Market Street, according the Pennsylvania Historical Society), publishing the popular Pennsylvania Gazette. Inoculation surfaces more prominently beginning in the 1730s, according to Boudreau.

Observing reports that inoculation is protecting people, he first writes to his sister in 1731 about the accounts of smallpox and inoculation outcomes in Boston, noting that only two out of 72 died, compared to one in four who died “the common way” from smallpox.

He prints a similar report in his paper.

“So this is classic Ben Franklin, who was one of our earliest american scientist. He is looking at the data,” says Markel.

But perhaps an even bigger turning point in Franklin’s rise to a key proponent of inoculation was the death of his son Francis “Frankie” Folger Franklin.

A personal tragedy

Born in 1732, Frankie was the apple of his father’s eye.

“This baby was just the greatest baby in the world, according to Ben Franklin. He was just a brilliant gifted child,” says Markel. “In fact, Franklin even got a tutor for his son when the boy was only two!”

Frankie had a case of “the flux” or diarrhea, and so Franklin decided to hold off on inoculating him until he was well. This was amid another wave of smallpox in Philadelphia. Frankie catches it and dies at the age of 4 in 1736 (he’s buried next to Benjamin at Christ Burial Ground in old city, with the phrase “The Delight of All Who Knew Him” on his gravestone).

Franklin is devastated, but to make matters worse, rumors began circulating that the baby developed smallpox from an inoculation gone awry.

Franklin, who by now has become an influential community leader, then makes a public statement in his paper, refuting the story.

From then on, it appears there’s “an almost vengeful intelligence after this that he’s studying smallpox, that he’s looking at inoculation,” says Boudreau.

But by late 1730s, for example, Ben Franklin is taking a real public stance.

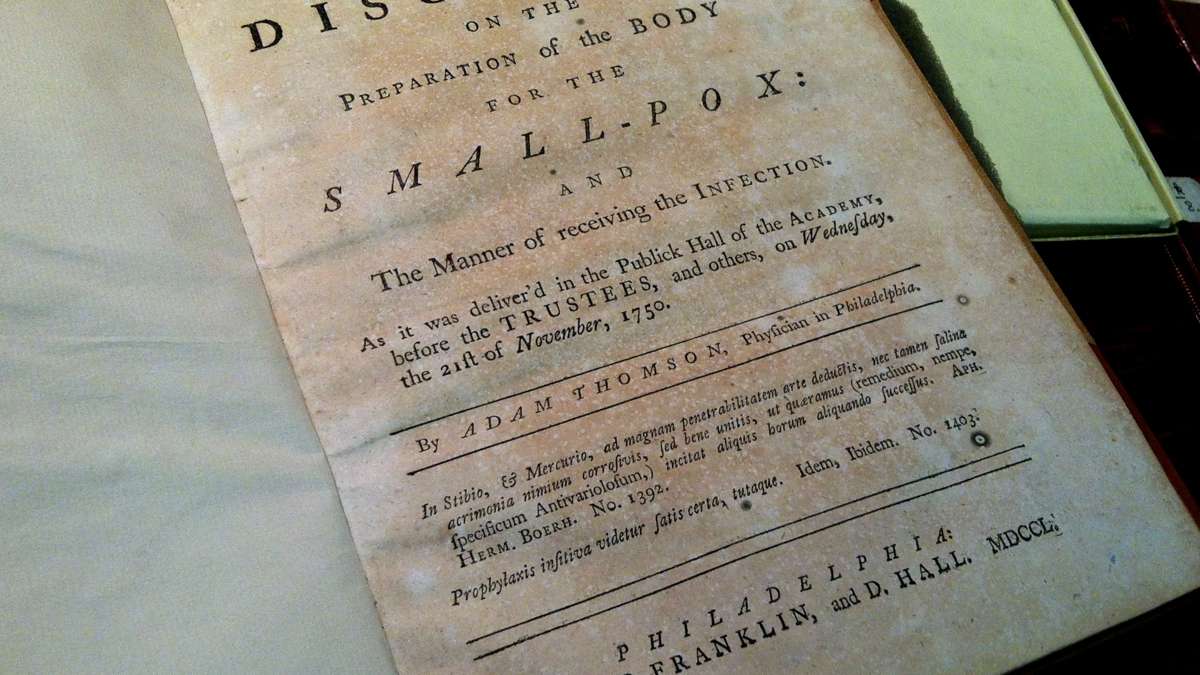

“He commissioned an English Physician, William Heberdon, to write a discourse on inoculating for smallpox at home,” says Karie Youngdahl, a vaccine historian at Philadelphia’s College of Physicians. “So this is a procedure parents could do for their own children if they didn’t have money to hire a physician.”

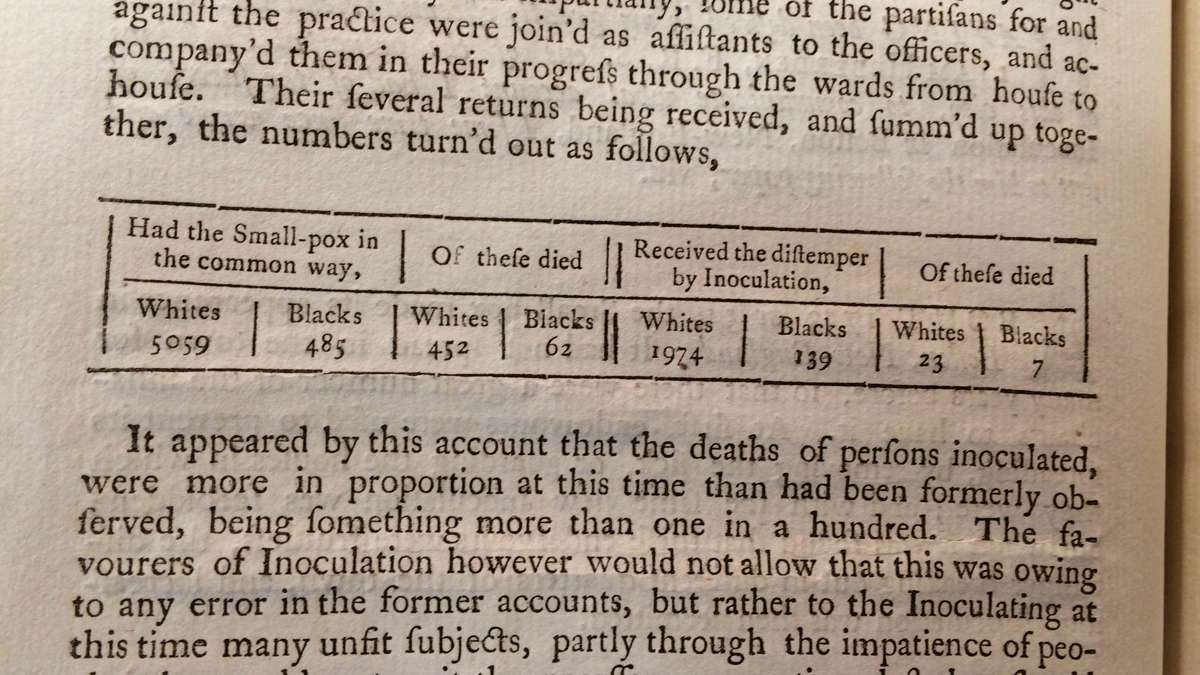

The pamphlet contains some of the first actual epidemiological data on inoculation, presented in surprisingly modern tables.

In 1774, Franklin creates the Society for of inoculating the Poor Gratis, a fund to help poor families get inoculated.

Despite all of this, Ben Franklin only mentions inoculation once in his autobiography in reference to his son:

“I long regretted bitterly and still regret that I had not given it to him by Inoculation; This I mention for the Sake of Parents, who omit that Operation on the Supposition that they should never forgive themselves if a Child died under it; my Example showing that the Regret may be the same either way, and that therefore the safer should be chosen.”

Benjamin Franklin would die just six years before the introduction of the first vaccine in 1796. It would be based on a modified version of the virus, so it would be much safer.

The vaccine was for small pox.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.