Philly area lawmakers using tax dollars on Twitter and Google ads, not just postage

Listen

Brian Meehan (Image courtesy of the Philadelphia DA's Office)

Congressional watchdog groups say lawmakers in the Philadelphia area are blurring the line between their campaigns and their official duties.

A longstanding policy allows members of Congress to send mail to constituents with a signature in lieu of postage, then later reimburse the U.S. Postal Service.

Once exclusively used for material sent by mail, the privilege of elected office known as franking now extends to lawmakers’ purchases of Facebook, Twitter and Google ads.

To see what lawmakers send voters — on your dime — you’d have to go to the basement of a House office building. Photos are banned. Only black and white copies leave the sparse room.

And lawmakers are alerted each time a reporter, researcher or, say, a political opponent asks to see what they’ve sent voters.

Why all the secrecy? Melanie Sloan, the director of Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, known as CREW, said it’s because there’s a thin line between official constituent services and campaigning.

“I think it’s complicated because we’re also in a permanent campaign. So no one’s ever finished campaigning,” she said. “And everything particularly a House member puts out is always geared toward persuading their constituents that they should be re-elected next cycle.”

Surprised by critics

Most lawmakers brush aside criticisms like that. U.S. Rep. John Carney, (D-Delaware), spent $80,000 in taxpayer funds using the franking privilege with just under $30,000 going to newer, electronic forms of communications.

“It’s hard to believe critics of it argue that we shouldn’t be doing it,” Carney said. “Then you have to ask yourself, how should we be communicating with our constituents?”

The Senate caps franked mail spending at $50,000 a year, so most senators don’t use the privilege because it’s hard to communicate with an entire state with that amount.

But there’s no franking limit in the House.

Communicating or campaigning?

From 1997 to 2008, eight House members averaged just over $50,000 in annual spending on franked mail.

U.S. Rep. Mike Fitzpatrick, (R-Bucks County), spent more than $200,000, including numerous Facebook ads inviting people to “like” his page. Some declare his support for gun rights while others rail against the IRS and the Affordable Care Act a.k.a. Obamacare. Fitzpatrick says franked mail is about two-way communication with constituents.

“It’s my obligation to see those letters, to respond substantively, directly … but also to have the resources to be able to give that response” he said. “So whether it’s mail back to my constituents in response to their questions or using technology to communicate better through things like telephone town halls I think that’s helpful.”

Representatives are given a certain office budget based on their distance from Washington and the cost of real estate back home. The average is around $1.4 million. Rank-and-file members are only allowed 18 staffers, but they can opt for fewer aides and spend that money on franked mail.

Fitzpatrick says he’s not abusing the franking privilege.

“I’m also mindful that these are tough economic times,” he said. “I always try to turn back resources back to the federal government at the end of my two-year term — underspend the budget and give the money back to the taxpayers, because that’s what I believe in.”

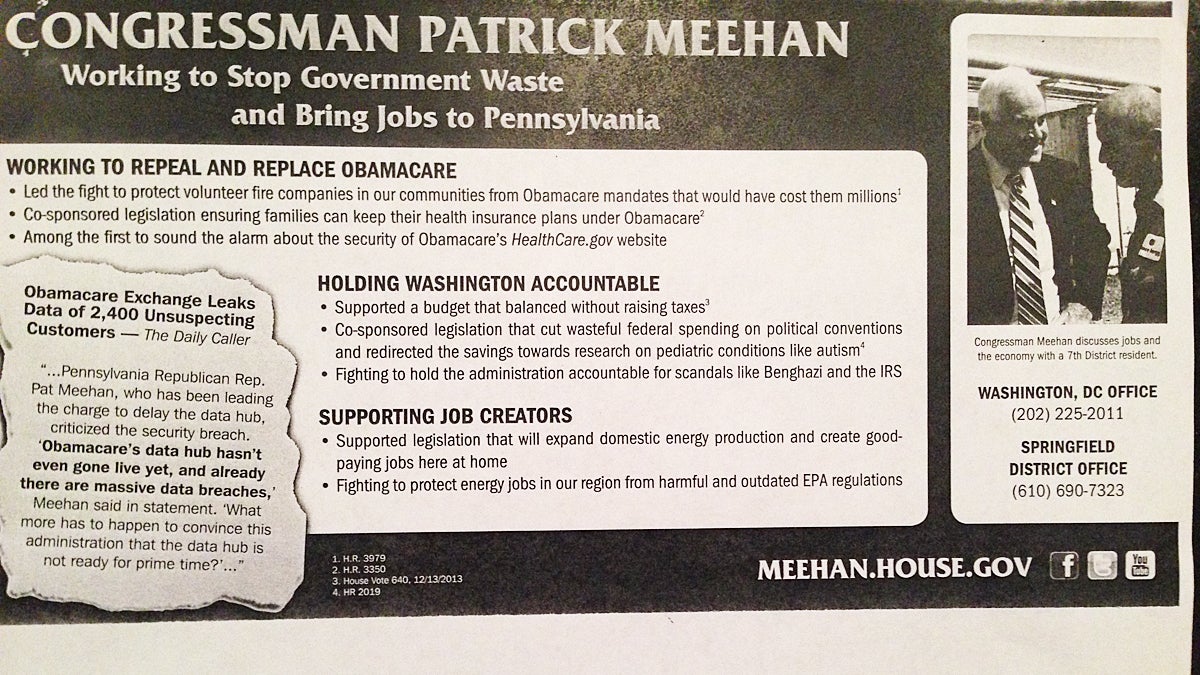

Remember that campaign slogan “Repeal and Replace Obamacare”? U.S. Rep. Patrick Meehan, a Pennsylvania Republican who represents parts of five counties, promised just that in a mailing printed on thick, color stock. Of lawmakers in the Delaware Valley, he’s spent the most on franking: $238,000.

“I think it’s an appropriate use when done on things that help the people understand the work you’re doing,” Meehan said.

Ten-term U.S. Rep. Chaka Fattah, (D-Philadelphia), spent $33,000 using the privilege. He used it more in the days before before he amassed a larger social media following.

“There have been years in the past where we have tried to purchase email addresses in the district for, say, the city of Philadelphia, and then you can kind of surf out there and people can decide if they want your newsletters or not,” Fattah said.

Sloan, of the watchdog group CREW, said it’s important for elected officials to communicate with the people who put them in office. But a lot of what’s considered franked mail nowadays — such as those Facebook and Google ad buys — isn’t what the nation’s first Congress intended when it adopted the practice, she said.

“I’m not sure that they have been updated to take into account the burgeoning variety of ways members can connect with their constituents,” Sloan said. “I think there are real questions about what is appropriate use of taxpayer dollars.”

Lawmakers aren’t allowed to use taxpayer funds for mailings within 90 days of an election, so lawmakers were cut off from using the franking privilege in August. But, if Sloan’s right, the campaign season started long before then — or never really ended.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.