More efficient, more data-reliant farming is on its way

Listen

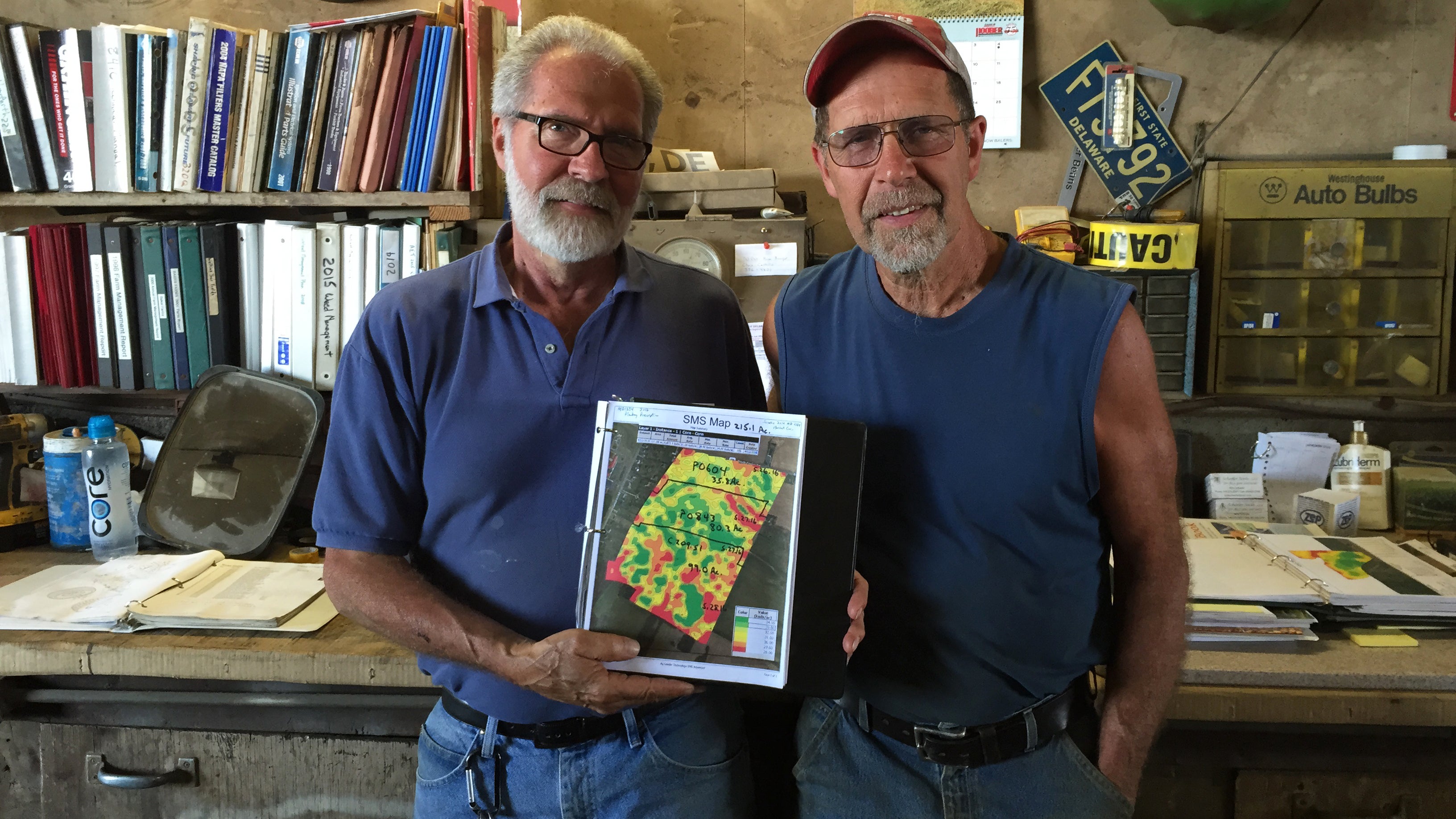

Dave and Ed Baker have been farming their land in Delaware since the 1960s. They started adopting precision ag technology in 2002. (Irina Zhorov/The Pulse)

At the Hoober farm store in Middletown, Delaware, there’s all the usual machinery – tractors, generators, sprayers, planters. But outside salesman Dave Wharry’s office, there’s also a stand with a couple of screens on it that look like fancy GPS monitors.

The computers actually are GPS enabled but they go onto farming equipment rather than cars. He turns on the computers and illustrations of fields appear on the screens. It’s pre-programmed to simulate a tractor driving through the field. The computer flashes tons of information: the speed of the machine, fuel use, moisture of the crop, how much it’s harvesting.

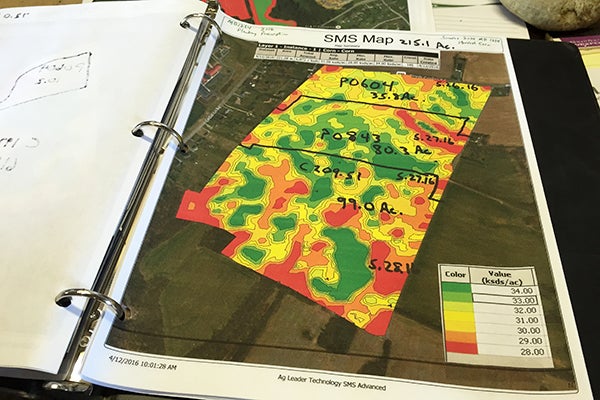

When the farmer is done harvesting, the computer makes a yield map showing which parts of the field produced best, and which ones returned fewer bushels. A farmer can use that information to make site-specific decisions. Instead of treating an entire field homogenously, they can say: maybe this weak area needs more fertilizer, or perhaps this productive section can support more seeds.

Each field is a snowflake, with different qualities and needs. The technology – called precision agriculture – allows farmers to take that into account in managing their operations. “Commodity prices aren’t growing, they’re dropping, costs are continually rising, so there’s a big push for efficiency,” said Wharry.

Savings in the details

Baker Farms, about ten miles from Wharry’s office, spreads over 1,700 acres and produces corn, soybeans and wheat. Its owners have been dabbling with precision ag since 2002, and got serious about adopting it in 2008. Ed and Dave Baker have been farming the land there since the 1960s, but they say it was one of their farm managers who kept up with technology in the industry and convinced them to try it. Before that, they usually made management decisions based on prior experience.

“There’s an old farmer saying that goes: 10 years to know a wife or a farm. You just farm the same ground for years and years and you know where the most productive fields are,” Ed Baker said. He said that piece is still important, “but now that we have the data we can make decisions that are based on real numbers and real science.”

The Bakers use their yield maps, along with soil maps, to vary seeding rates. They used to plant each field with a constant number of seeds. Now, in very productive areas, they plant 34,000 seeds per acre and on the poorest soils they plant 28,000, with gradations in between. In all, they have seven management zones. Seven snowflakes.

The Bakers’ prescription map, which tells the seeding machine where to vary the seeding rate within one of their fields. (Irina Zhorov/The Pulse)

Their prescription map, which tells the machine how much to plant where, looks a lot like a topographical map, with each ring of elevation actually representing a seeding rate zone.

They load the prescription into the computer on the corn planter, and as it moves across the field, it controls the flow of seeds, shutting off nozzles on the 30 foot machine, as needed.

The technology can also be used to make prescription maps for fertilizer, applying it more deliberately in the area of the seeds and varying quantity, as needed, across a field.

In the past, it was not possible to vary seeding or fertilizer rates – the nozzles were either on, or off. “The farmer would’ve had to get off the tractor, take a wrench and change things mechanically, and that just took too long,” said David Bullock, who teaches in the agriculture department at the University of Illinois.

Too, machines didn’t shut off at the end of a row while the farmer made a turn in the tractor, and they didn’t ‘know’ whether it was passing over a row that had already been treated. “All of a sudden, with computers, GPS, it can all be done automatically, and easily,” Bullock said.

Saving product – whether seed or chemicals – through more judicious management can also save money. In the case of fertilizer, not putting down chemicals where they’re not needed can also have environmental benefits, in the form of reduced runoff into lakes and rivers.

The first year the Bakers used the technology, they found out they had bought 6 to 7 percent more seed than they needed.

Precision ag uncertainties

There’s just one issue: the machines can do anything farmers tell them, but what to tell them remains somewhat of a mystery. For example, a farmer may know his corn grows better in one section than another, but being able to quantify that relativity into applicable numbers – add 100 pounds of nitrogen in one zone, 120 in another – is difficult.

“When we know an area is low and another area is high, we know put more and less, it’s just we’re not very precise in how much more or less we would need to put on,” said Doug Beegle, who teaches in the agriculture department at Penn State University. “There’s still a fair amount of uncertainty there.”

While Beegle said even relying on educated, localized estimates is better than treating fields as uniform entities, Bullock is more doubtful. “I’m not convinced that there’s been that much benefit from precision agriculture,” he said.

For Bullock, farmers, agronomists, and the universities that generate ag research never figured out how to accurately quantify seed and fertilizer needs according to farm conditions (including soil types, weather, etc.). There are many variables to consider and in the past, to simplify, the industry relied on simple but ineffective formulas.

In other words, even as technology has marched on, no one has figured out what to input into the computers.

But Bullock said additional data can fix that. With more data, you can better characterize farm conditions and develop formulas to increase efficiencies.

He just received a grant to use the precision ag technology – which, after all, is really good at generating data – to run field trials. They’ll run 100 experiments over the next four years focusing on seeding rates and nitrogen use. They’ll also work with researchers in South America.

The idea is to find patterns in the test plots. “You can statistically estimate, you know, how does clay content of the soil, say, how does that tend to affect how much nitrogen we should put down? Now, does it? I don’t know. But you can look at that sort of thing, and more complicated things, with statistics” he said.

He wants to eventually distill all that data into software that would help agronomists give better advice to farmers everywhere, even where precision ag technology is not available.

The Bakers, meanwhile, are happy with what they’ve been able to do so far with their seeding program. They haven’t tried varying fertilizer rates, yet. That, they said, is too expensive. “Every decision that a farmer makes on an investment, or a return on investment, it’s a financial decision,” Ed Baker said.

Many precision ag computers come standard on new equipment, but upgrades to more complex systems can run in the tens of thousands of dollars. Wharry, who sells the machines, said many farmers get a return on their investment within a couple of years. But as precision ag is refined and proves itself to more farmers’ wallets, smart tractors may just become regular old tractors.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.