Nature's grip: Scientist examines gecko feet to develop new medical adhesives

A Villanova University biologist is studying how geckos stick to surfaces in an effort to replicate this mechanism for new medical adhesives

Listen 8:37

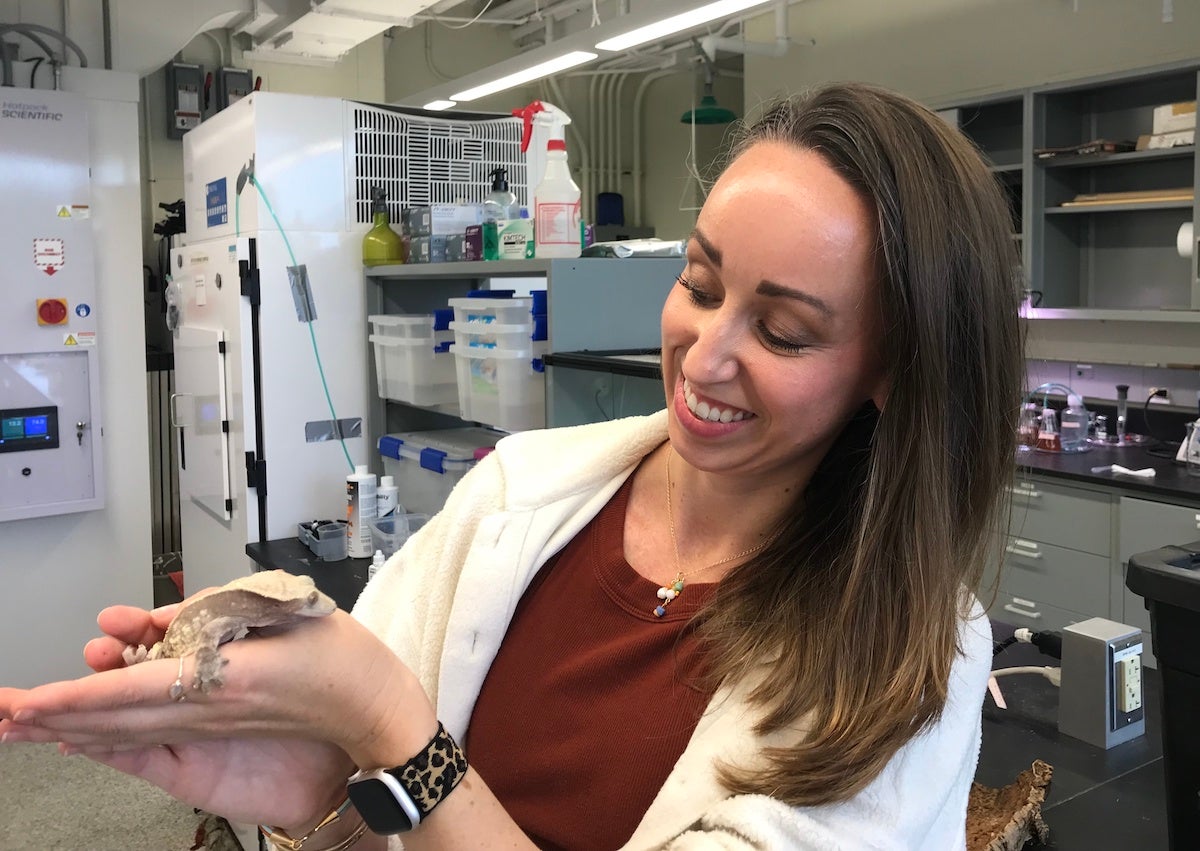

Tokay geckos are studied for their ability to stick to surfaces at Villanova University's Stark Lab. (Maiken Scott/WHYY)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

If biologist Alyssa Stark could choose an animal superpower, she would borrow some abilities from geckos.

“They can run up and upside down. They can run sideways. They can stick to pretty much any surface,” said Stark. “They have an adhesive system that works over and over again on a variety of surfaces in a variety of contexts. They can run across or hold on to bark and rough surfaces, dirty surfaces, warm surfaces, humid surfaces, some wet surfaces, and even glass.”

Stark is trying to figure out exactly how geckos stick to surfaces in her lab at Villanova University. It houses several geckos in temperature controlled chambers. Some of them are tokay geckos, they’re brown and about the size of a human hand.

Stark takes one of the geckos out of its terrarium, to get a closer look at its feet.

“The toes are kind of fat for what you might think a lizard toe looks like,” she said. “That’s because geckos have evolved these flattened toe pads.”

Each toe pad has many lines across it, and each line is filled with tiny, tiny microscopic hair-like structures.

“So that’s how they adhere,” said Stark. “The other organisms that I study use various types of glue, but geckos don’t. They have a dry adhesive system. So by having so many hairs on their feet, they kind of are multiplying the contact area that they can make with a surface.”

Stark says the main mechanism most likely is Van der Waals adhesion, a weak intermolecular attraction between the little hairs on the geckos’ toes and whatever substrate that they’re on.

“So when that becomes multiplied with all of those tiny little nano-structure contacts on their toes, those weak intermolecular Van der Waals forces that we might not even notice between our own hand and a surface get multiplied to the point where they’re very sticky,” said Stark.

Stark tests the geckos’ speed and stickiness in different situations to understand and replicate this complicated adhesive system to create new applications for humans, especially in health care.

“There’s a big push towards medical adhesives because the gecko foot and those adhesive pads are soft and they don’t require glue, so you’re not actually gluing skin that could be delicate.”

Subscribe to The Pulse

She says this could be important especially when working with infants or elderly patients who have sensitive skin.

“You’d have this soft adhesive that’s strong and easily peeled off, and can do that over and over again, so you don’t have to keep replacing medical tape,” she explained. Like gecko feet, the tape would also stick and stay on despite sweat or oil from patients’ skin.

Stark is part of a growing field called biomimicry. The idea is to look to nature with its seemingly endless examples of brilliant design and engineering, to learn how these systems work, and try to replicate them. It’s hard work, and humbling.

“We still don’t have this magic gecko tape that can do everything that a gecko can,” said Stark. “And I think it’s really because we’re still trying to figure out how the natural system works.”

Stark says it’s exciting to collaborate with experts from other fields such as architecture, engineering or design.

“Learning about how animals work is what biologists like me do,” said Stark. “But being able to share that information with people that I never thought I would share it with is just fascinating.”

She says it’s important to not just attempt to replicate designs that work in nature, but to also replicate their sustainable qualities, to use materials that are biodegradable, and to be conscious of energy use.

Stark also studies the adhesive mechanisms of sea urchins, she has a few of those in her lab, as well, and ants. She travels to tropical destinations and climbs giant trees to examine their admirable sticking powers.

“I work in Panama mostly and I really focus on canopy ants; ants that live in the tops of trees about 100 feet up or so.”

Stark climbs high up into these trees to collect different types of ants. She says she can find hundreds of different species up in these tree tops.

“When you get up there, the adhesives of these ants are specific to really hot surfaces in particular, their feet are walking on these hot surfaces.”

Stark says the ants stay put thanks to a chemical adhesive.

“They have a glue that can maintain adhesion in a variety of contexts, especially these hot surfaces, which could be useful for bio-inspired design. How do you have an adhesive that can stay stuck on something that gets really, really hot?”

Stark focuses on worker ants which don’t have wings.

“So there’s no backup plan. They’re not like a beetle or another insect that, if they fall, they can use their wings to fly. So I feel like ants are a great system because there’s no backup option.”

While Stark is focused on adhesive systems, other researchers are looking into different aspects of ant life they could potentially mimic, like organizational structures and communication.

“Things like the way ants move resources in their colony from one location to another, or the way they communicate. How do they move products? How do they develop and design larger structures? How do they build an actual nest?”

Stark says this information could be used by architects, or by CEOs to better structure social components of their work. And this could be an interesting direction for biomimicry.

“We’re not just making some cool new product, but actually solving the way our companies work and our systems work so that it’s more efficient, as well as actually, probably, more friendly towards us because after all we are animals.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.