Centennial Commons carves out space for East Parkside neighbors to connect

Ashley Hahn heads to Parkside Edge to see how this project aims to find new ways of connecting neighbors to W. Fairmount Park and strengthening the civic infrastructure.

Next up in our series about Philly’s changing public spaces, Ashley Hahn heads to Parkside Edge to see how this project aims to find new ways of connecting neighbors to West Fairmount Park and strengthening the community’s civic infrastructure.

—

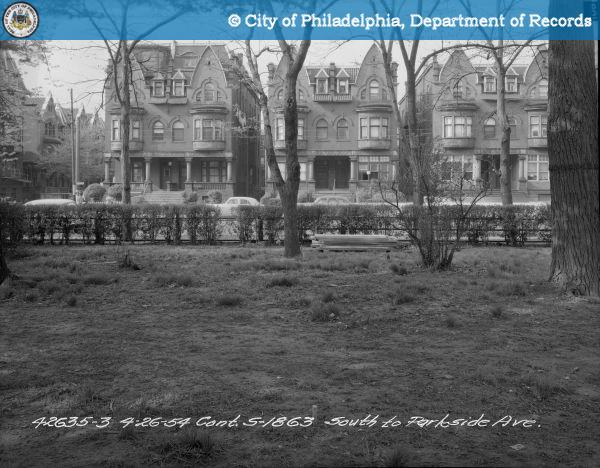

A row of richly detailed, Roman brick residences lines the long 4100-4200 blocks of Parkside Avenue, with terra-cotta flourishes, deep-set porches, and Flemish rooflines iced with copper. They were built by a beer baron in the 1890s, attracting solidly middle-class families. The exuberant architecture spoke to their pride of place, located just across the street from where the 1876 Centennial Exhibition was held. Today, West Park’s Centennial District still unfolds here, more than 700 leafy acres peppered with relics from the fair.

This part of the park is so vast, you could set six football fields end zone-to-end zone from 41st Street to Belmont Avenue, stacked two deep between Parkside Avenue and Memorial Hall, and still have room to spare. There’s plenty of park, but few amenities much worth neighbors crossing Parkside Avenue to experience.

Still, Parkside residents do spend time in this part of West Park, and some have lifelong associations with it. Plenty of older neighbors used Memorial Hall when it was a rec center and recall a sense of freedom on summer days spent exploring Fairmount Park. Kelly Pool, next to the Please Touch Museum in Memorial Hall, remains a big draw in summertime. Reunion picnics have long been an important tradition, as well. And many residents count the park as one of the blessings that come with living in Parkside, like a giant front yard for the neighborhood.

The landscape is historic but has endured years of neglect, particularly as decades of municipal belt-tightening led to leaner park budgets. The most basic amenities, like benches and trash cans, have been few and far between. There is one playground in the entire Centennial District.

Over the last 20 years, more than two dozen plans have tried to envision a new future for this legacy landscape, but few have delivered.

Yet, over the last year, a new strand of park spaces has been built facing Parkside Avenue, recasting the transition between the neighborhood and the vastness of West Park with a sequence of age-friendly spaces meant for socializing and relaxing. This is Parkside Edge, the $5 million first phase of a project called Centennial Commons, spearheaded by Fairmount Park Conservancy and designed by the landscape firm Studio Bryan Hanes.

Instead of underutilized lawns, Parkside Avenue from 41st to Belmont now features gardens and seating areas, defined by a low white rope, that divide 67,000 square feet of parkland into more manageable spaces. The “porches” – a nod to those on Parkside’s high-style buildings – are framed by 68 new trees and more than 42 plant species that will add color and texture as they grow. A band of rain gardens buffers the outdoor rooms from the sidewalk.

The completion of Parkside Edge will be celebrated on June 13 with a ceremonial ribbon-cutting. But the neighbors have already started spending time in the new park spaces.

Parkside Edge is physically oriented toward the neighborhood, designed to invite residents to claim their space in West Park. This part of Fairmount Park is otherwise dominated by regional attractions, like the Mann Center for the Performing Arts and the Please Touch Museum, that the city estimates draw 1.7 million visitors annually.

“The park is something that everybody owns. It can bring everybody together in a geographic sense, but it’s also a public asset that lots of folks in the neighborhood care about,” said Jamie Gauthier, the conservancy’s executive director. “If people come to the table about the park, that can also help the community to build its civic infrastructure to shape other things.”

New experiences in a familiar landscape

On a warm evening last month, I spent time in Parkside Edge with a group of neighbors. As we walked from Viola Street toward Parkside Avenue, friendly banter floated on a gentle breeze.

Entrances to the new park’s “porches” align with the streets feeding into Parkside Avenue, creating new vistas into the park from neighborhood streets. We crossed into a porch at 42nd Street, walking over a short metal bridge spanning the rain garden, like a little planted moat to absorb stormwater. The sun was low in the sky, and the seating area was comfortably shaded.

“It’s just so peaceful and serene. In this crazy world we live in now, we need that,” said Gloria L. Pemberton, an East Parkside resident since 1983. It was her first visit to the new park. “I’m glad we have a place like this.”

Neighbors remarked how nice it felt to be there, testing out the new porch swings, suspended from white A-frame stands. The swings have white metal frames with slender wood slats, and they’re are easy to sit on or get up from because their range of motion is limited, just enough for visitors to gently sway.

Some benches match the swings, made from wood and metal, while others are backless slabs of solid stone. Those are set toward the rain gardens, allowing people to face the street or into the park.

Pemberton said she could envision reading and relaxing in the park now. Roberta Lighty-Connor agreed as they shared a swing, saying the park is a much nicer place for kids to play than her block is. She has lived in the neighborhood for 10 years, since moving into her husband’s parents’ house.

“I keep saying this is the beginning of East Parkside’s renewal,” said Lighty-Connor. Even though residents have worked hard for years to improve the neighborhood, she said the park project is different. In part, she thinks that’s because people have such personal connections to it through things like annual picnics and family events. The park is shared space, and that’s something to build from.

Rodney Sheppard grew up in Mantua but has lived in East Parkside for the better part of a decade. Fairmount Park was his sanctuary growing up, and he still loves spending time in it during special events or to find a little peace. “I would climb a tree as high as I could, and sit in it for an hour or two and just dream about my life. Or what the world was going to be like. That was my favorite thing to do as a child.”

Albert Johnson has lived in East Parkside since 1965 and has built plenty of memories in the park over that time. He can picture the park’s old border – a metal fence along the sidewalk, a hedgerow inside the fence line, and then a row of benches. People would sit on the fence and wait for the bus, he said. And he remembers sitting with girlfriends on those benches, just hidden enough for teenage dates. “I will never forget about it,” Johnson said, cracking up his neighbors.

Each porch feels big enough to have personal space if you’re there alone, but intimate enough to make striking up a conversation feel easy, he said. “I would ask, do you live around here, what’s your name, that way I would try to make friends.”

“Oh, it’s great,” enthused Callalily Cousar, president of the longstanding East Parkside Residents Association, as she settled into a swing. She has lived in the neighborhood since 1947 and is a respected advocate for East Parkside. This evening was her first visit to the new park spaces. As we lingered, she kept having ideas about what to add, stoking a conversation among residents about the space. “Young people are going to want to do more than look across the street,” she said. They suggested more flowers to add color, some temporary shade until the trees mature, a drinking fountain, and maybe tables where people could play chess or cards.

Terrell Watson, one of those younger residents, walked over with his dog to chat. He thought the space was ideal for an older crowd, but said it felt “like a little getaway” to him. In future phases, he’d want to see more furniture for outdoor eating or fitness activities.

There is certainly more to come. Parkside Edge is just the first phase of the ambitious Centennial Commons project, a collaborative effort by Fairmount Park Conservancy, city agencies, Centennial Parkside Community Development Corporation, neighbors, and philanthropic supporters to adapt part of West Park into a series of more dynamic places with new relevance for Parkside neighbors.

The conservancy started thinking about working in the Centennial District more than a decade ago. In early 2013, it began meeting in earnest with East Parkside neighbors. Jennifer Mahar, Fairmount Park Conservancy’s senior director of civic initiatives, said she’s attended about six community meetings in the neighborhood each month for the last five years. She also spent a lot of time listening and talking on stoops and in people’s kitchens. And it’s clear that many people in the neighborhood see her, and by extension the conservancy, as a committed community partner.

In 2015, Centennial Commons was one of five projects selected to be part of Reimagining the Civic Commons, a national initiative piloted in Philadelphia and jointly funded locally by the William Penn Foundation and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. [Disclosure: Both foundations provide grant support to WHYY. This series is supported by a grant from the Knight Foundation.]

When it is completed, Centennial Commons will encompass an area between Kelly Pool and Parkside Avenue, with several new park experiences, including a skating loop and teen zone. It will also have as its centerpiece an elaborate interactive playground, inspired by the area’s innovation history, interpreting the Corliss steam engine that powered the 1876 Centennial Exposition and captivated public imagination. It’s estimated phase two will cost $8 million.

For now, the conservancy wanted to start with Parkside Edge because it aims to serve near-neighbors first. If it led with the fancy new playground – something residents say they want – the conservancy worried it would be adding another amenity with regional draw, in an area already full of such attractions. Instead, it hopes Parkside Edge can get people excited about helping to shape the next phase, and build a new sense of ownership among residents for the park.

“We really wanted to deliver for the community. We responded to a specific desire from the community to have a more intimate space to gather within the park,” said Gauthier. “Hopefully, that gives us stronger ties for delivering phase two, and that it helps to build the trust that we need to move forward.”

Mahar said the primary goal for Parkside Edge is “to draw neighbors across Parkside Avenue into the park into spaces they can enjoy together.” The conservancy and Centennial Parkside CDC are also planning programming they hope will invite more neighbors to do just that.

Two clear community priorities are the need for local job creation and youth programming. So the question has become how those intersect with Centennial Commons and the organizations’ other work in East Parkside.

Programming for youth matters, Mahar stressed, because 27 percent of East Parkside’s residents are children under the age of 18 (slightly higher than the citywide average) and more than 60 percent of them live in poverty. The park is massive, and existing play spaces elsewhere in the neighborhood are well-used. In play areas at Centennial Commons, the conservancy hopes to support creative play through features that involve healthy elements of risk that build resilience, too.

As for jobs, Centennial Parkside CDC and the conservancy are in the process of jointly hiring a program manager – ideally someone from the neighborhood. They also work together to support the CDC’s “Clean and Green Team” of three individuals who help maintain public spaces in the neighborhood. As the Centennial Commons project grows, its staffing needs will also expand. So the partners are looking ahead to job training and hiring opportunities there, as well.

Programming at Parkside Edge will begin this season, building on events already hosted in connection with the Civic Commons initiative over the past two summers. In 2016, there was the Viola Alley Connector event, a festival highlighting neighborhood heritage, culture, fresh food, and featuring temporary installations designed to reinforce the connection between the neighborhood and the park. It was so successful that Centennial Parkside CDC and Reading Terminal Market created Parkside Fresh Food Fest, which brought fresh-food access and cooking demonstrations into shared spaces on Viola Street over six summer Thursdays last year. The partners hope to bring it back this year, but move its location to Parkside Edge.

“Some residents still, I don’t think, feel a strong connection to Parkside Edge or know what it is,” said Chris Spahr, who became Centennial Parkside CDC’s first director in 2017. “Programming this summer is going to be really critical, because if residents start to see things that reflect their desires, wants, needs in that space, they’ll start using that space.”

Last weekend was the 11th annual West Park Arts Fest, which moved to an area adjacent to Parkside Edge and welcomed some 2,300 people. Centennial Parkside CDC and Fairmount Park Conservancy participated in the event, taking the opportunity to talk with residents and share their work in the neighborhood. The organizations are also planning a movie night in mid-August with a back-to-school emphasis, in the hope of drawing families into the park who might not otherwise be engaged with the project or partners. And their work together in the neighborhood won’t stop at the park’s boundary.

“What I would love is to work with the community organizations to build a broader set of partnerships that not only benefit what’s happening at the park but benefit the community,” Gauthier said. What if the park could be the hub that helps bring more resources to help meet community needs? For now, she said, it’s about working with residents to define their priorities and “using our investment in the park as leverage to bring other folks to the table, and as a way of showing other partners that now is the time to really dig in with this community.”

Reconstructing the park, building community

I met Tineesha Tarboro as she stood on one of the tall stoops across from the new park, outside the apartment building where she lives with her family. Before construction, she said, her family treated the Centennial District like a big backyard. She said she’d wondered if the new park space was private, feeling uncertain about who would be allowed to use it and how. While the project was under construction, it was an inconvenience made worse by what she felt was inadequate public information.

“They took all the parking, they took our backyard, there was no communication and no advance notice.” She works and has a young family, so it’s hard to make it out to dinnertime community meetings. Tarboro said she got a leaflet on her car, telling her to move it to make way for the street work, but that was all she heard. “You can flyer my car but can’t tell me what’s happening in the park?”

Parkside Avenue has been redesigned alongside Centennial Commons, aimed at making the crossings between the park and neighborhood easier. But Tarboro was among the neighbors I spoke with who don’t think the street redesign is successful – so far at least. Cars still whip past, paying no attention to the new pedestrian-activated blinking light, bouncing off pedestrian islands and new curb bump-outs. One day I visited, a street sign was plowed over.

While Parkside Edge offers a new amenity to the neighborhood, its success isn’t the most pressing concern for a lot of residents. Still, the hope is that by investing in the park, the process will help strengthen the neighborhood’s civic fabric, and in turn, stimulate economic and community development.

As a kid growing up in East Parkside, Michael Burch said he would spend entire summer days in the park, leaving in the morning and not coming home until supper. He biked all over Fairmount Park, he said, and his mother never had to worry. During the 1970s and ’80s, with the rise of gang activity, the park stayed neutral ground, he said. “It was a life apart.”

The neighborhood has changed a lot since then, Burch said. “There weren’t these vacant spaces. Kids played in the street. We played in the park. Everybody had a job, often two-income families. Things were different then.”

By day, Burch works in youth education at the Franklin Institute. And after moving back to Viola Street 10 years ago, into the house where he grew up, he got to work in the neighborhood too. He helped co-found the Viola Street Residents Association, which has largely focused on improving quality-of-life issues, greening, and addressing vacancy. He also created the Parkside Journal, a hyperlocal news source, to make sure residents have access to information about what’s happening in their neighborhood.

After three decades of population loss, Parkside residents like Burch see the neighborhood stabilizing and poised to grow. They know its assets will help: beautiful historic buildings; the park just blocks away; and relative affordability as other areas of West Philly become more expensive. The mantra is to be prepared for change, Burch said.

People in Parkside are accustomed to hearing about ambitious plans, not watching them realized. So when Parkside Edge broke ground, some neighbors were on high alert.

“If residents don’t actually physically see something, it doesn’t impact them, it’s just another plan. But here, when they saw bulldozers at the park, it was very physical. It was very real,” Burch said. “Right away, people were suspicious. They thought, ‘This is not for us. This is part of the plan to move us out.’ I’m not going to be naïve, you do have to keep an eye on that. But you do want to enjoy the amenities that these changes bring.”

Parkside is in a precarious state – for every house fixed up, another seems to decline. Some residents see the investment in the park as an indicator that the neighborhood is changing, and maybe not for them. Several elders told me that they constantly receive unsolicited mailings from people offering to buy their homes.

“These things come in the mail, there’s an influx of new residents, the new park development. All that adds up to a certain amount of fear that people have,” Burch explained. Change can be scary, but the neighborhood could use some change, too – the question is, what kind. In the last year, it lost its last sit-down restaurant (though there are hopes a new business will soon take over). The neighborhood businesses he grew up going to – a barber, a cleaner, a small grocery – are long gone.

Several longtime Viola Street residents I spoke to said they can’t remember the last time the street was paved. It’s pockmarked with potholes, and certain sidewalks are crumbling to the point of disappearance. Still, there are so many signs of a flourishing community where people take pride in working together.

Joyce Smith is a West Philadelphia native who moved with her husband, Randy, to East Parkside 12 years ago, drawn to the neighborhood’s historic architecture and the community’s activist spirit. And then, she said, there’s just something special about the way her block feels.

As we talked, sitting in her living room one evening, sounds of Viola Street drifted in through her open windows – kids playing, a radio, neighbors sitting out and chatting. Residents most often compare this block of Viola Street to a little village where people look out for one another. They have reclaimed vacant lots, getting cars towed, then planting and mowing these spaces themselves. They also have grown food in the Viola Street Community Garden since the 1960s, an important intergenerational space where neighbors new and old work together. Some houses are vacant, but plenty more are lovingly cared for and beautiful examples of sensitive preservation.

Smith also helped form Viola Street Residents Association and began working with neighbors to address quality-of-life issues. Over the last 10 years, she said, she has seen its work pay off – more people take pride in where they live and share responsibilities tending the block. As contagious as the Viola Street residents’ work seems, it’s an all-volunteer effort with some practical limitations.

As Smith put it, “If it’s taking the street that long, how long do you think it’s going to take the neighborhood? And some blocks aren’t getting the same kind of attention.”

Smith is passionate about housing preservation in East Parkside. By day, she works at Philadelphia Legal Assistance, helping homeowners facing foreclosure and collections activity. And she brings the spirit of that work home, too. She is especially concerned with addressing the pressure abandonment and speculation put on the neighborhood. She said she sees ever more out-of-state license plates slow-cruising the block, as faceless companies keep buying properties. Meanwhile, some houses are in limbo, their fates complicated by entangled ownership issues, or at risk of demolition. In Centennial Parkside CDC, founded in 2015, Smith sees the best vehicle for working on those challenges, and she joined the board early on.

“The CDC was formed by a group of very strong-minded residents who recognized that there was just a vacuum in this neighborhood, there was no strong representation to represent this community to developers, to City Council, to funders,” said the group’s Spahr. In that way, the CDC can complement the work of long-tenured and respected groups like East Parkside Residents Association. But it still needs to earn the community’s trust.

The park project didn’t lead to the CDC’s formation, but it has certainly accelerated its growth. It has helped attract new resources to support the CDC’s work, particularly funding from the William Penn Foundation and John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, which also funded Centennial Commons. Fairmount Park Conservancy also supported the fledgling CDC from the beginning, Gauthier said, because it recognized “that in order to have authentic engagement and a partnership with community, there needs to be some formal civic infrastructure to connect to.” Especially as Centennial Commons launched.

Gauthier said the conservancy is currently trying to deepen its partnerships in the neighborhood, particularly as everyone continues to parse tough questions about advancing equitable development as new investment comes to East Parkside. “We’re sensitive to the discussion about open-space investments leading to gentrification, but we believe everybody deserves great parks. So we also want to also make investments in the community so it can lead the way.”

In the scope of the whole landscape, Parkside Edge is just a sliver. But layer it onto the community-driven energy already happening in East Parkside, and it’s a potent opportunity. It creates space for people to come together, organize, and collectively build power through a project that will potentially influence the trajectory of the neighborhood.

—

In Common is made possible through support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.