Can old coffee cause yellow fever?

Listen

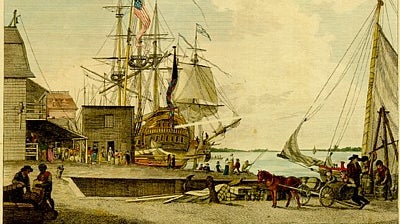

The Arch Street wharf

Of course it can’t! But funny what a little bit of misinformation can do in the midst of an outbreak.

The hot zone, in 1793, was centered along the banks of the Delaware.

“In the space of two months, approximately 5,000 Philadelphians died of yellow fever. At the time, Philadelphia was the nation’s capital,” says David Barnes, professor of the history of medicine and public health at UPENN. “It truly was a national crisis.”

The mosquito-borne illness shut down the federal government and caused 20,000 of the city’s 50,000 residents to flee. But it wasn’t insects that were catching the blame.

“It would have been ridiculous to think that mosquitoes were part of the cause of yellow fever in 1793 simply because there are always mosquitoes in the summer in Philadelphia, and yellow fever does not always come,” says Barnes.

Instead, some prominent doctors of the day were pointing in another direction, down toward the riverfront.

“The leading theory of the origin of that epidemic was the dumping of a cargo of coffee beans on Ball’s Wharf that had rotted. The very first cases…the patients and their family members and their neighbors had been complaining for weeks about this foul odor on the wharf,” he says.

According to Barnes, there’s little in the way of historical evidence about the pile of coffee beans itself—including its size or how it was eventually disposed of—but the concept that somehow a discarded shipment from the West Indies could be blamed for the deaths of 5,000 people struck him as curious.

“I always thought that the idea of rotting coffee was very strange, because coffee smells so wonderful and it is just incongruous to think of coffee smelling so horrible that it could disgust people and cause an epidemic,” says Barnes. “So I wanted to make coffee rot and see what it smelled like, and that is the origin of this little experiment.”

And that is how a group of about two dozen people came to find themselves smelling rotting coffee in a parking lot on Race Street between Second and Third streets last Friday evening.

“We can see where Ball’s Wharf used to stand from here,” Barnes says, pointing eastward. “That’s just about two blocks that way, directly underneath what is, today, Interstate 95.”

The event, dubbed a “pop-up history” lecture, is aimed at enticing interested pedestrians to learn more about the city’s past, and get their own whiff of rotting foulness.

Barnes has come armed with 50-pounds of putrid beans he let decay in his driveway all summer, much to the chagrin of his wife. The result is splashed out onto a tarp, after which he reads from an account of Dr. Benjamin Rush, North America’s most famous physician at the time.

“Mrs. Bradford had spent an afternoon in a house directly across from the wharf and dock to which the putrid coffee had emitted its noxious effluvia a few days before her sickness, and had been much incommoded by it…After this consultation, I was soon able to trace all the cases of fever which I have mentioned to this source.”

Reactions to the 2014 version of the smell ranged from “meh” to sinus horror.

“There’s like a hint of coffee, but is mostly rotten. I mean, it is completely rancid,” says Elaine LaFay. “I feel it travel up my nasal cavity into my brain in a weird sort of way.”

Other tasting notes were more direct.

“Lingering vomit,” offers Maxwell Rogoski.

“I actually feel sick standing here, so to imagine that this could be the cause of a disease like yellow fever…I totally believe it,” says Deanna Day.

That immediate response to search for blame, to target the innocent, is a hallmark of past epidemics, and it persists today.

“I’m not sure we can entirely prevent misinformation,” says Barnes. “I think we can be as honest as we possibly can about what we know, and what we don’t know. What we can do, and what we can’t do, but there’s always going to be fear and uncertainty. As long as you have a fatal disease that’s essentially untreatable, you are going to have fear.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.