Avoiding diabetes discrimination and stigma at work

Listen-

-

-

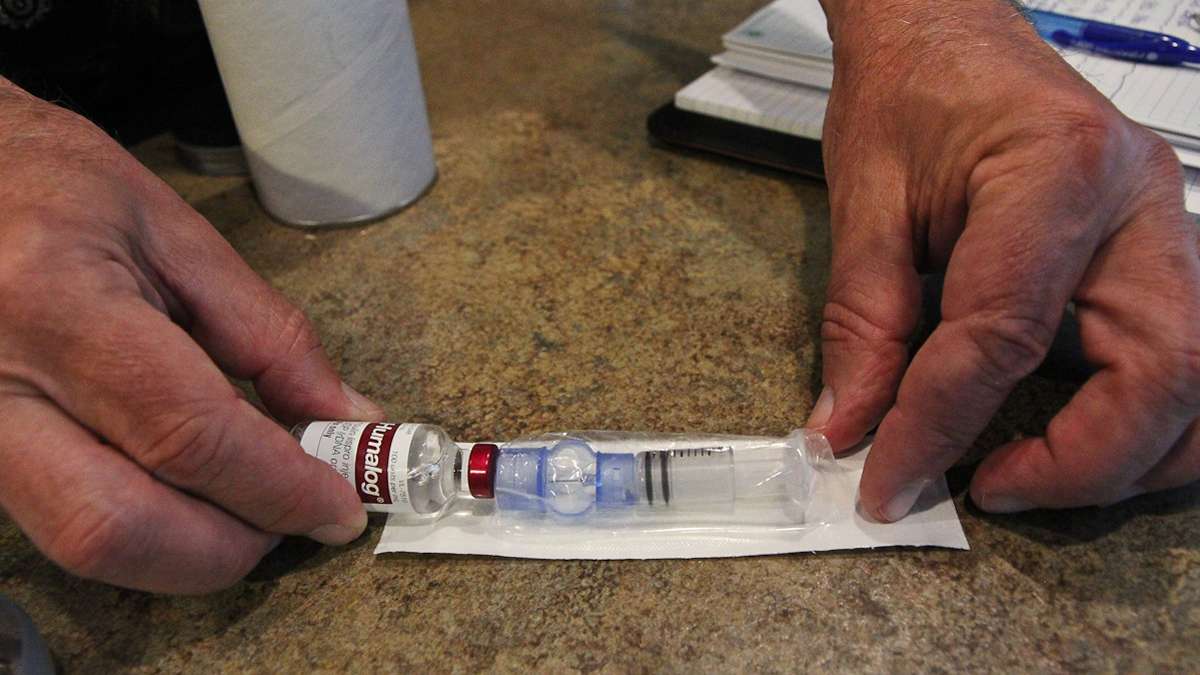

Randy Childress says management at his last job had a hard time understanding that he needed to take time during the work day to have snacks and inject insulin. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Managing diabetes takes time and effort. So, how do you do that.. at work?

We all know someone with diabetes. The count has soared so high, it’s easy to ignore the latest alarming statistic.

Twenty-nine million is the government’s newest estimate on the number of Americans with diabetes. That’s more people coping with diabetes at work and more workplaces managing people with diabetes.

Internist Christina Stasiuk, medical director with the insurance company Cigna, says one of her jobs is to help employers understand the scope of the epidemic—and the health care dollars spent on it.

“It’s extremely expensive to treat diabetes,” Stasiuk said. “If it was expensive but not very many people had the disease, that wouldn’t be a big deal. It’s a big deal because so many Americans have it, more are getting it and so many people have it and don’t know,” Stasiuk said.

Diabetes and its related complications racked up $245 billion in medical costs, lost wages and work in 2012, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Stasiuk said complications really drive up costs including blindness, amputations, stroke, heart attack and kidney failure.

Insurance companies and large employers like to talk about the programs, the education classes and coaching they’ve set up to promote worker wellbeing. It’s harder to get companies to talk specifics about how they handle it when someone with diabetes needs to inject insulin on the job or when a worker wants to take an extra snack break.

The results of health screenings and other insurance-related benefits remain confidential. But Stasiuk said at some point, dealing with diabetes at work may become a question for human resources and management.

“If you need accommodations on the job, your boss has to know because your boss needs to be able to adjust your work schedule to manage your diabetes,” she said.

Fear of potential stigma

Endocrinologist Intekhab Ahmed, with Jefferson University Hospital, said he’s happy to write a doctor’s note to help things go smoother for his patients at work, but he said–in his experience–most of the time, problems don’t start with the workplace—they begin with the diabetic.

Many of his patients are hesitant to take steps to control their diabetes at work, he said. Some people don’t want to prick their finger on the job or keep a glucose meter at the office.

“They don’t want to be stigmatized. They don’t want other people to know,” Ahmed said.

Diabetes is a disease that needs to be monitored closely, and Ahmed tells patients to think about their blood sugar like a termite.

“It’s eating the house, but you don’t see any destruction, then suddenly the house collapses,” he said.

A big dip in blood sugar could be a big safety concern.

Ahmed said he worries about some patients who aren’t managing their condition well – those who work as roofers or truckers or in other safety-sensitive jobs.

From an employer’s perspective

He also understands the worries of employers who hire people with diabetes.

“You have to take extra steps, extra measures for that particular person. I can see when you are running a business, when you are dealing with numbers, what would you do?” Ahmed said. “It depends on the patient. If they are taking care properly they should be just like anybody else who does not have diabetes.”

Some companies use diabetes as a reason to not to hire.

“Unfortunately it happens all the time. Often—though—it is in violation of a number of laws including the Americans with Disabilities Act,” said attorney Gregory Paul, a legal advocate for the American Diabetes Association.

Paul said employers in the transportation and law enforcement industries—in particular—get concerned that a worker with diabetes will have a medical emergency.

“Our point is that most people don’t experience hypoglycemia, or severe hypoglycemia to the extent that it would interfere with work at all,” Paul said.

Protecting people with diabetes

Paul said he’s working to fight discrimination.

Companies are allowed to evaluate if a worker can safely do a job, but that assessment is supposed to come after someone is offered the position.

“That’s really at the heart of the ADA [Americans with Disabilities Act]–to provide an individualized assessment rather than a blanket ban,” Paul said.

In 2008, a rule change made it clear that the Americans with Disabilities Act protects people with diabetes.

Paul said too often employers find out someone has diabetes, then assume there’s going to be a problem.

A few cases end up in court, but Paul says most disputes about “reasonable accommodations” get settled with a few phone calls and some negotiation.

“Particularly when we can get the doctors talking,” Paul said.

“I think the vast majority of people with diabetes are able to work without any accommodations, able to work without any necessity of sharing that information with their employers or coworkers,” Paul said. “It’s a private matter. To kind of flag that person could be inviting desperate treatment or discrimination that’s, of course, unwelcome.”

Advocates say diabetes seems to draw especially uninformed stereotypes. A lot of jokes are shame-based and advance the idea that some diabetics are to blame for getting the illness. For example, this electronic greeting card reads “Billy has 32 candy bars. He eats 28. What does he have now? Diabetes. Billy has diabetes.”

Obesity is one of the leading risk factors for one kind of diabetes called type 2, but family history, ethnicity and race also play a role.

Discrimination and lack of understanding at work

Glen Mills, Pa., resident Randy Childress says he faced ridicule when he tried to manage his condition on the job.

Childress has type 1 diabetes. His pancreas does not function properly, so his body produces almost none of the insulin it needs to digest and balance out glucose–or sugar. Childress says at the car dealership where he worked, checking his blood sugar regularly became a problem.

“It happened several times that I just wanted to check my sugar before the next people came in and I had to take an automobile out on the road,” Childress said.

“I would have a sales manager say, ‘I have to see you right now.’ I go: ‘Just one second.’ ‘I have to see you, now.’ I would say: ‘Just wait one minute.’ It was one more reason for them to join the chorus, and say: ‘What is with this blood sugar thing?'”

Childress wears an insulin pump that works like a mechanical pancreas to deliver steady doses of medicine.

“Even when I’d have some success and I’d sell a car or have someone close on a car, I would be congratulated by: ‘Way to go Pump Boy.’ I did say one time, you really shouldn’t call me that and the comment was made: ‘Well, you’re not going to fall down and roll around are you?’ Meaning some type of diabetic fit,” Childress said.

Childress said he also got flak for trying to manage his blood sugar by eating small snacks throughout the day.

“That’s the way I dealt with it discretely,” Childress said. “It was said to me on several occasions: ‘didn’t you have your lunch break? Didn’t you eat lunch earlier?’ And you just can’t keep saying: ‘Listen I’m a diabetic; I’ve got to eat this food.'”

Childress said there was no human resource department at the car dealership where he could plead his case.

He was fired in January.

“It’s impossible to say that they let me go because of my diabetes. Any job, anywhere can find some other way to rationalize somebody being laid off,” he said.

“They didn’t understand it and I really wasn’t there to educate them about what diabetes was all about,” Childress said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.