Allentown’s famed Cadets rise again after months of scandal and tumult

Some had worried a #MeToo scandal would be fatal for one of the nation’s oldest and most decorated drum corps.

For more about the future of the Allentown Cadets, click the play button above to hear WHYY reporter Nina Feldman’s interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer/Daily News’ Tricia Nadolny.

—

Claire Albrecht already knew that George Hopkins had enemies. So when he called to warn her that a news article with unflattering allegations against him would be published the next day, she decided to not worry.

He told her it was all lies. She told herself it would blow over.

Instead, on the morning of April 5 she read about a man she didn’t recognize, accused of sexual misconduct by nine women over his nearly four decades as director of Allentown’s famed Cadets drum and bugle corps. Within hours Hopkins resigned. And Albrecht, a youth leader in the corps, was left to imagine something previously inconceivable: the Cadets without a man who seemed a part of the corps’ very DNA.

“Only knowing the Cadets having George as a director, it was definitely so much of a shock to me that I was like, ‘There’s no way he’s going to be gone,’ ” Albrecht, the corps’ 21-year-old drum major, said. “I don’t know the Cadets without him there.”

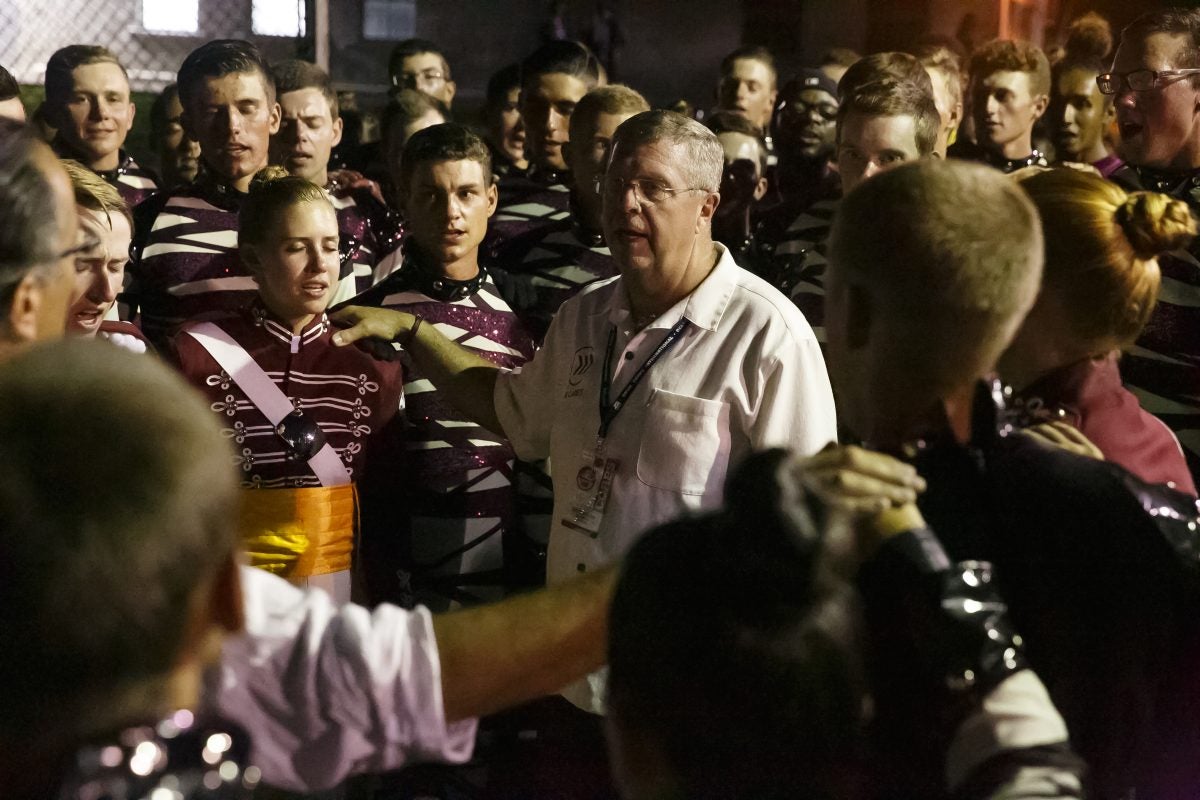

Yet on Saturday night beneath the lights at a football field in Allentown, there they were, performing the first home show of their summer tour. Some had worried the scandal would be fatal for one of the nation’s oldest and most decorated drum corps.

But when the #MeToo movement struck the Cadets, left behind were a group of members and alumni, shell-shocked and grief-stricken, who still cared deeply for the organization. Not a single of the corps’ 154 members withdrew. Alumni stepped up to fill leadership roles previously held by Hopkins and a board of directors that resigned amid the scandal.

“It’s very overwhelming,” said Scott Litzenberg, a former Cadet who left his job teaching high school marching band in Kennett Square, Chester County after 34 years to become the corps’ new director. His voice cracked, which happens often these days when the gravity of the moment hits him.

“A lot of people are looking at me going, ‘What are you going to do to fix this?’ ” he continued. “We’re just going to take care of the kids and do the right thing. And the rest will take care of itself.”

The task is daunting. Hopkins had run the corps, whose members travel the country each summer performing marching band numbers in pursuit of a national title, since 1982. He did so with a dominating presence — and many say a tight grip on every aspect of the organization, from the show’s creative direction to the instructional style to operations.

Over the decades, hundreds of Cadets have looked up to him as a mentor. His “Hop Talks,” motivational speeches given to the corps members, were a mainstay of the summer. Former Cadets say the life lessons he preached have resonated for them far beyond the fields of drum corps.

Others, though, knew him for his volatile temper. More than a dozen current and former employees recently told an investigator hired by the Cadets that he regularly yelled at and demeaned his staff. Many alumni said he made them feel unwelcome, strangers within a corps they considered family.

(Hopkins has denied any non-consensual sexual relations with his accusers and declined interview requests.)

Before the show Saturday, a few dozen alumni gathered for a picnic in a park beside the stadium. Around them, the melodies of corps preparing for the night’s performances rolled over the grass. Under a white and yellow striped tent in the sweltering heat, they swapped stories from their marching years and caught up with old friends.

Many said they can see the corps is moving in the right direction and forging a new identity without Hopkins. The pain, though, is still raw.

Robin Karpinski marched in the 1984 Cadets color guard alongside three women who have now accused Hopkins of abusing them when they were members. They won the Drum Corps International finals that year.

“I’ll never forget that feeling. The roar of the crowd and the lights and the sweat pouring off. And it was worth it,” she said. “But you know, 34, 35 years later to find out that this happened with people that I marched with, I don’t even know the words to describe it. Upsetting is just too nice, too light of a word to describe it. These were my sisters next to me in the line.”

Nearby were three of the women who went public with their accusations against Hopkins. Their stories sparked not only changes for the Cadets, but also a reckoning within the national drum corps community over sexual harassment and whether enough has been done to protect members, staff and volunteers.

One of them, Kim Carter, trembled as she arrived that day. She knew Hopkins would not be there. But she still felt the familiar anxiety that had plagued her at other shows over the years, where she feared running into him.

“I’m glad it came out. I wish it could have come out years ago,” Carter, who lives in Warrington, Bucks County, said. “But it’s still hard, no less. It’s still hard.”

Also there were twin sisters Linda and Lee Ann Riley from Langhorne, Bucks County. Though it had been months since they went public — accusing Hopkins of separately approaching each of them for sex when they were members of the corps in the 1980s and he was their director — being face-to-face with the Cadets community filled them with a fresh fear.

It melted away as they made their way into the picnic. All afternoon, they barely stepped a few feet before someone wrapped them in a hug.

Their tears flowed freely, then continued later in the stands as they saw, for the first time in decades, the Cadets take the field. When the performance began, they watched with their eyes wide and hands at their faces, wincing and then sighing with relief each time the color guard members threw their flags into the air and caught them with a clean finish.

As the show’s final note echoed and faded into the night air, the sisters cradled one another.

“We had to be here for this,” Lee Ann said to her sister. “We had to be here.”

After the scores had been handed out, the corps packed up for a 7-hour drive to Lawrence, Mass., where they would perform the next night. By this weekend they will be in South Carolina, then Missouri by the next weekend, and Texas the next.

As she headed towards the bus, 20-year-old Sara Bowden, the group’s horn sergeant, said drum corps has already taught her so many valuable life lessons. It dealt her a painful one this year: people are not always what they present themselves to be.

“Trying to cope with that and also get ready for the 2018 season was definitely difficult,” she said.

The veteran, in her third year marching, said she has found comfort in her relationships with the Cadets’ rookies.

A corps without George Hopkins is all they have ever known.

—

Tricia L. Nadolny: tnadolny@phillynews.com Twitter: @tricianadolny

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.