Some ‘cheaper’ health plans have surprising costs

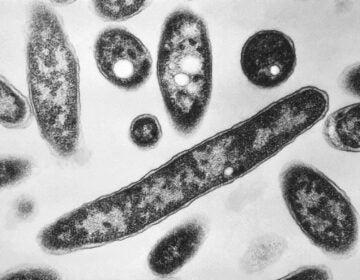

One health insurance startup charges patients extra for procedures not covered by their basic health plan. The out-of-pocket cost for a tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy might range from $900 to $3,000 extra, while a lumbar spine fusion could range from $5,000 to $10,000 (Frederic Cirou/PhotoAlto/Getty Images)

One health plan from a well-known insurer promises lower premiums — but warns that consumers may need to file their own claims and negotiate over charges from hospitals and doctors. Another does away with annual deductibles — but requires policyholders to pay extra if they need certain surgeries and procedures.

Both are among the latest efforts in a seemingly endless quest by employers, consumers and insurers for an elusive goal: less expensive coverage.

Premiums for many of these plans, which are sold outside the exchanges set up under Affordable Care Act, tend to be 15 to 30 percent lower than conventional offerings, but they put a larger burden on consumers to be savvy shoppers. The offerings tap into a common underlying frustration.

“Traditional health plans have not been able to stem high cost increases, so people are tearing down the model and trying something different,” said Jeff Levin-Scherz, health management practice leader for benefit consultants Willis Towers Watson.

Not everyone is eligible for a subsidy to defray the cost of an ACA plan, and that’s led some people to experiment with new ways to pay their medical expenses. Those experiments include short-term policies or alternatives like Christian sharing ministries — which are not insurance at all, but rather cooperatives where members pay one another’s bills.

Now some insurers — such as Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina and a Minnesota startup called Bind Benefits, which is partnering with UnitedHealth Group — are coming up with their own novel offerings.

Insurers say the two new types of plans meet the ACA’s rules, although they interpret those rules in new ways. For example, the new policies avoid the federal law’s rule limiting consumers’ annual in-network limit on out-of-pocket costs. One policy manages that by having no network — patients are free to find providers on their own. And the other skirts the issue by calling additional charges “premiums;” Under ACA rules, premiums don’t count toward the out-of-pocket maximum.

But each plan could leave patients with huge costs in a system where it is extremely difficult for a patient to be a smart shopper — in part, because they have little negotiating power against big hospital systems and partly because illness is often urgent and unanticipated.

If these alternative plans prompt doctors and hospitals to lower prices, “then that is worth taking a closer look,” says Sabrina Corlette, a research professor at Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute. “But if it’s simply another flavor of shifting more risk to employees, I don’t think in the long term that’s going to bend the cost curve.”

Balancing freedom, control and responsibility

The North Carolina Blue Cross Blue Shield “My Choice” policies aim to change the way doctors and hospitals are paid by limiting reimbursement for services to 40 percent above what Medicare would pay. The plan has no specific network of doctors and hospitals.

This approach “puts you in control to see the doctor you want,” the insurer says on its website. The plan is available to individuals who buy their own insurance and to small businesses with one to 50 employees. It’s aimed particularly at consumers who cannot afford ACA plans, says Austin Vevurka, a spokesman for the insurer. The policies are not sold on the ACA’s insurance marketplace, but can be purchased off-exchange from brokers.

With that freedom, however, consumers also have the responsibility to shop around for providers who will accept that amount of reimbursement for their services. Consumers who don’t shop — or can’t because their medical need is an emergency — may get “balance-billed” by providers who are unsatisfied with the flat amount the plan pays.

“There’s an incentive to comparison-shop, to find a provider who accepts the benefit,” says Vevurka.

The cost of balance bills range widely, but could be thousands of dollars in the case of hospital care. Consumer exposure to balance bills is not capped by the ACA for out-of-network care.

“There are a lot of people for whom a plan like this would present financial risk,” says Levin-Scherz.

In theory, though, paying 40 percent above Medicare rates could help drive down costs over time if enough providers accept those payments. That’s because hospitals currently get about double Medicare rates through their negotiations with insurers.

“It’s a bold move,” says Mark Hall, director of the health law and policy program at Wake Forest University in North Carolina. Still, he says, it’s “not an optimal way” because patients generally don’t want to negotiate with their doctor on prices.

“But it’s an innovative way to put matters into the hands of patients as consumers,” Hall says. “Let them deal directly with providers who insist on charging more than 140 percent of Medicare.”

Blue Cross spokesman Vevurka says My Choice has telephone advisers to help patients find providers and offer tips on how to negotiate a balance-bill. He would not disclose enrollment numbers for My Choice, which launched Jan. 1, nor would he say how many providers have indicated they will accept the plan’s payment levels.

Still, the idea — based on what is sometimes called “reference pricing” or “Medicare plus” — is gaining attention. Under that method, hospitals are paid a rate based on what Medicare pays, plus an additional percentage to allow them a modest profit.

North Carolina’s state treasurer, for example, hopes to put state workers into such a pricing plan by next year, offering to pay 177 percent of Medicare. The plan has ignited a firestorm of opposition from hospitals in the state.

Montana recently got its hospitals to agree to such a plan for state workers, paying 234 percent of Medicare, on average.

Partly because of concerns about balance-billing, employers aren’t rushing to buy into Medicare-plus pricing just yet, says Jeff Long, a health care actuary at Lockton Companies, a benefit consultancy.

Wider adoption, however, could spell its end.

Hospitals might agree to participate in a few such programs, but “if there’s more take-up on this, I see hospitals possibly starting to fight back,” Long says.

What about the bind?

Minnesota startup Bind Benefits eliminates annual deductibles in its “on-demand” plans sold to employers who are opting to self-insure their workers’ health costs. Rather than deductibles, patients pay flat-dollar copayments for a core set of medical services, from doctor visits to prescription drugs.

In some ways, it’s simpler: No need to spend through the deductible before coverage kicks in or wonder what 20 percent of the cost of a doctor visit or surgery would be.

But not all services are included.

Patients who discover during the year that they need any of about 30 common procedures outlined in the plan, including several types of back surgery, knee arthroscopy or coronary artery bypass, must “add in” coverage, spread out over time in deductions from their paychecks.

“People are used to that concept, to buy what they need,” said Bind’s CEO Tony Miller. “When I need more, I buy more.”

According to a company spokeswoman, the add-in costs vary by market, procedure and provider. On the lower end, the cost for tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy ranges from $900 to $3,000, while lumbar spine fusion could range from $5,000 to $10,000.

To set those additional premiums, Bind analyzes how much doctors and facilities are paid, along with some quality measures from several sources, including UnitedHealth. The add-in premiums paid by patients then vary depending on whether they choose lower-cost providers or more expensive ones.

The ACA’s out-of-pocket maximums — $7,900 for an individual or $15,800 for a family — don’t include premium costs.

The Cumberland School District in Wisconsin switched from a traditional plan, which it purchased from an insurer for about $1.7 million last year, to Bind. Six months in, according to the school district’s superintendent, Barry Rose, the plan is working well.

Right off the bat, he says, the district saved about $200,000. More savings could come over the year if workers choose lower-cost alternatives for the “add-in” services.

“They can become better consumers because they can see exactly what they’re paying for care,” Rose says.

Levin-Scherz at Willis Towers says the idea behind Bind is intriguing but raises some issues for employers.

What happens, he asks, if a worker has an add-in surgery, owes several thousand dollars, then changes jobs before paying all the premiums for that add-in coverage? “Will the employee be sent a bill after leaving?” he wonders.

A Bind spokeswoman says the ex-employee would not pay the remaining premiums in that case. Instead, the employer would be stuck with the bill.

Kaiser Health News, is a nonprofit news service and editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation. KHN is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))