From the US Capitol to local governments, disinformation disrupts

The disinformation and "big lie" of election fraud motivated many people to storm the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6. (Matt Williams for NPR)

One day before the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol in January, thousands of miles away in northern California, anger began to boil over at a meeting of the Shasta County Board of Supervisors.

“This is a scamdemic, it’s a plandemic, and it’s a damndemic. We’re sick of it!” one woman shouted.

Again and again, residents railed against public officials for enforcing social distancing rules. Some warned of “civil war” and possible violent resistance from militias and other groups.

The potential consequences of false ideas played out in deadly form on Jan. 6, when extremist supporters of former President Donald Trump – inspired by his lie that the November election was stolen – attacked the Capitol. But widespread acceptance of disinformation is shaping the political process at all levels of government.

Dangerous disinformation

Conspiracy theories, disinformation and distrust in the election system have sewn controversy, and even violence, at all levels of government in recent months. In several communities – including Sequim, Wash., and San Luis Obispo, Calif., local officials’ support for the baseless QAnon conspiracy theory has angered and divided residents.

Last year, the FBI foiled a plot to kidnap Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer. Several of the right-wing extremists arrested in connection with the plot appeared to have been influenced by unfounded conspiracy theories including QAnon.

In Shasta County, which is heavily rural, mostly white, and strongly leans Republican, many residents are upset with their government – an anger fueled, in part, by false conspiracy theories that have taken root online during the coronavirus pandemic, which has killed more than 50,000 Californians.

Despite a vote by a majority of Shasta County board members to meet virtually that day, because of the virus, two board members who showed up in person allowed members of the public inside the board chambers, where they took turns expressing rage at county officials.

“When the ballot box is gone, there is only the cartridge box. You have made bullets expensive, but luckily for you ropes are reusable,” one man shouted.

Supervisor Leonard Moty, a retired police officer who participated remotely, watched with concern as it all played out online.

“It really served no purpose,” Moty said, “other than to allow a certain group of people who’ve been very vocal, and continue to attack the board, the state, the governor. They don’t believe in wearing masks. They sort of have said many times that if less than 1% of the people are dying, what’s the big deal, which I find very offensive.”

Destabilizing democracy

The next day, as insurrectionists motivated by Trump’s election lies stormed the Capitol, Moty said he couldn’t help but wonder if something like that could happen in Shasta County.

Andra Gillespie, a political science professor at Emory University in Atlanta, said growing disenchantment with the political process, fueled by widespread misinformation, can breed political violence and insurrection.

“Will people who feel disaffected not show up in elections and kind of become indifferent to everything?” she said. “Or will they be compelled to engage in other forms of political activity that would be destabilizing?”

Another danger, Gillespie said, is bad policy – promoted through false narratives. She points to efforts by Republican lawmakers in several states to pass new voting restrictions, saying they need to protect election integrity after Trump’s loss.

In reality, Gillespie said, those measures would disproportionately hurt lower-income voters, people of color and Democrats.

“What does it mean when you see legislators responding with legislative and policy proposals that would be aimed to address a problem that in fact didn’t exist in the first place?” Gillespie said.

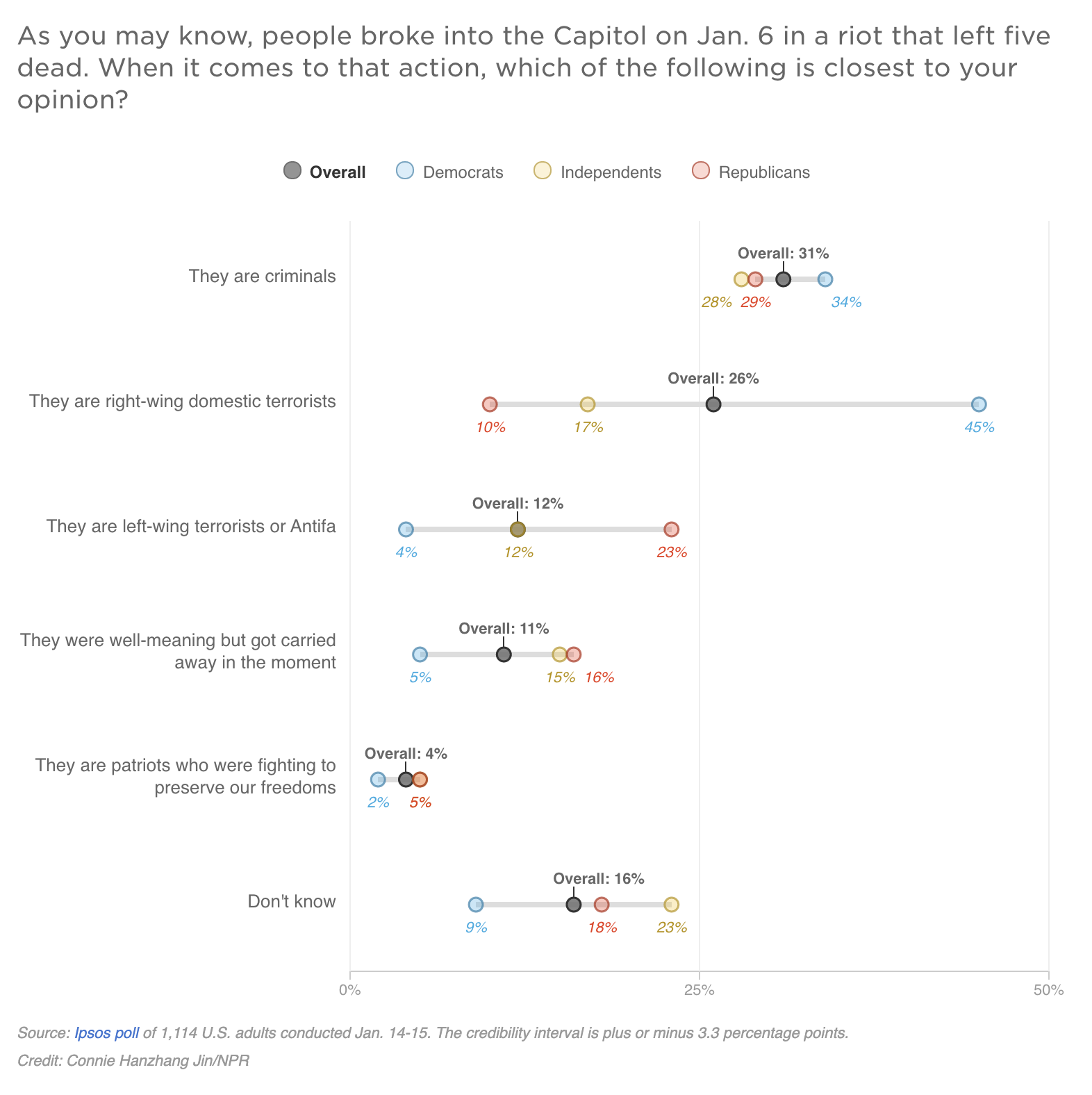

An Ipsos poll taken after the attack on Jan. 6 found that only 27% of Republicans believed that Joe Biden legitimately won the presidential election, and one-third of all respondents expressed the false belief that voter fraud helped him win. More than three-fourths said they fear political violence in the next four years.

Disinformation also spread about the Capitol riot. One-fifth of poll respondents believed the unfounded claim that the people who broke into the building were actually undercover members of Antifa, and Republicans more likely to identify the rioters as left-wing terrorists or Antifa.

Distrust and disruption

In Shasta County, Supervisor Leonard Moty said that even though there hasn’t been violence there, the political process has been disrupted. The board has a lot of work to do at each meeting – managing things like public health, law enforcement, and roads.

“The extremists aren’t the majority at this point so business can still be done, but it’s much more difficult,” Moty said.

Board meetings used to take two or three hours, but now, they’re sometimes around six or even seven – a lot of that public comment, filled with personal attacks.

“There’s no constructive criticism,” Moty said. “It’s just trying to disrupt the meeting and disrupt county business. And I think you’ve already seen an example at the national level for quite a few years, where they’re in gridlock.”

Moty worries that reasonable residents won’t feel safe coming to public meetings – or running for public office.

Money, power and the ‘culture war’

Distrust in institutions and political polarization are a dangerous combination, according to Adam Enders, a political scientist at the University of Louisville. While false conspiracy theories have always been around, he said they’ve been embraced and promoted by growing number of influential leaders in recent years – from former President Trump to pastors to prominent business owners.

“And they have political reasons for doing this, whether it’s their consumer base or their congregation, winning this culture war or something along those lines,” he said.

Enders said that can create fertile ground for authoritarian leaders to manipulate the public and stoke political violence.

“Because the more that people lack confidence and trust in institutions, the more they’re willing to buck norms and ignore institutions when it’s good for their side,” he said. “That’s when we see institutions start to fall apart, and norms crumble – and that’s an environment that we can’t really predict.”

The Shasta County board recently voted to censure two members for involvement in opening up the board chambers to the angry crowd on Jan. 5. Those members did not respond to NPR’s requests for comment.

Leonard Moty said he hopes the country – and the country – will someday get back to a place where reasonable people can come together to solve problems through their government – but he’s not sure what it will take.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))