Red tape: The untold stories of Philadelphia’s 1950s teacher purge

New tapes shed light on an old story: the suspension of 32 Philly teachers during the 1950s. We explore what happened, and what it tells us about ourselves.

It began 70 years ago this month: June, 1952.

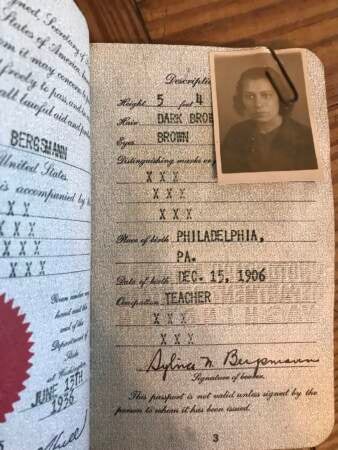

The superintendent of the School District of Philadelphia summoned a veteran English teacher named Herman Aaron Beilan to his office for what he described, in writing, as “a matter of importance.”

In this fateful meeting, the superintendent, Louis Hoyer, asked Beilan a question:

Were you, in 1944, press director of the professional section of the Communist Political Association?

We don’t know what Beilan thought as the question tumbled out of Hoyer’s mouth. Maybe he felt it coming. Maybe he didn’t. Maybe he wondered how the superintendent even knew about a political post he’d held eight years prior.

We only know that Beilan didn’t answer. He asked to consult a lawyer.

Hoyer said he could. Beilan left.

Six years later, Beilan’s attorney would retell that story for the United States Supreme Court. By then, Beilan had lost his job. He was tutoring on the side and selling cleaning products door to door.

Did the Constitution offer him any protection? Was an English teacher free to speak his mind outside the classroom and keep his job within it?

Today, seven decades after Herman Beilan walked into the superintendent’s office, we’re paddling through the same social currents that led to his firing.

Or maybe they never went away.

We in this country have a long fascination with the politics of teachers. What they believe. What they say.

Today, we might not ask teachers about Communism.

Perhaps we ask about the history books they assign. Or the sex education curriculum they use. Or what they’re posting on social media.

But we’re still asking. And watching.

In 1953, Philadelphia’s school board suspended 32 teachers with alleged ties to the Communist Party of the United States of America. Historically, these teachers have been a footnote. New York, as it often does, experienced a bigger, noisier version of what happened here in Philly.

In the absence of attention lies opportunity — a chance to rediscover stories and lives.

We are going to bring you to the moment when the government plucked a few dozen teachers from obscurity and paraded them before the city.

Then, we’ll explore the fallout — the lives lived after the Red Scare blew through town and the questions left in its wake.

Part 1: The Local

Our story begins not in post-war prosperity, but in the heart of the Great Depression.

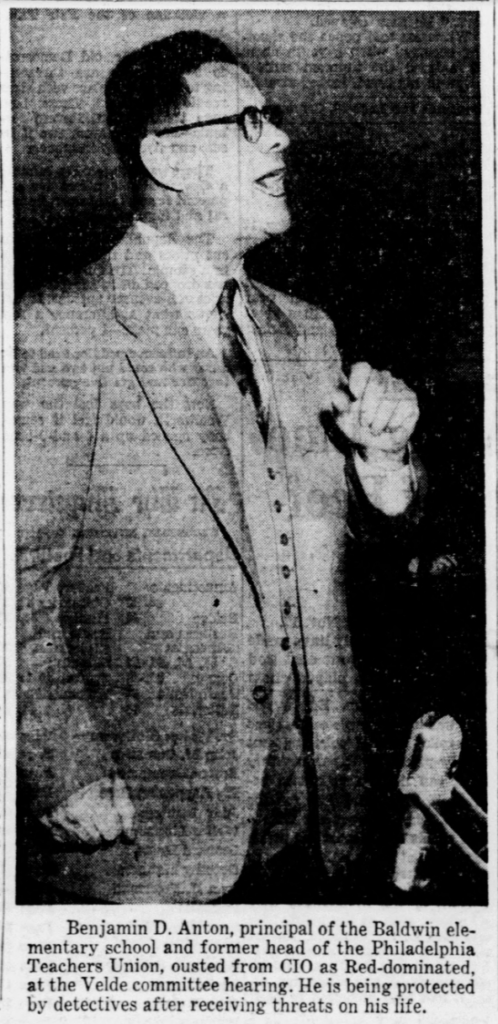

During the early 1930s, Philadelphia’s school system suffered from a combination of neglect and growing pains. Auxiliary principal Benjamin David Anton crisscrossed the city through those years, serving in “some 30-odd schools,” as he would later tell a congressional committee.

“Some were new buildings that were overcrowded as they were opened,” Anton said of the facilities where he worked. “Some were old buildings, fire traps. Some were buildings that had classrooms that had no windows. Some were buildings that had classrooms in the basement.”

At the time, school employees had relatively little power over their working conditions.

Salary schedules were set by state law. Districts could fire teachers at will — and often did. In Pennsylvania, it was common for administrators to dismiss women teachers when they married or became pregnant. Black teachers, segregated in their own elementary schools, faced fierce discrimination in hiring, firing, and promotion.

In 1932, as the economy tanked, Philadelphia cut teacher salaries without incurring much organized wrath. At the time, educators belonged to a smattering of professional associations that were supposed to represent their interests. But after the pay cut, those organizations “didn’t really do much to try to fight it,” says Nicholas Toloudis, a political science professor at The College of New Jersey who is working on a book about early teacher unionism in Philadelphia.

That inaction prompted a response. A small group of Philadelphia teachers decided to form Local 192 of the American Federation of Teachers.

For the first time, Philadelphia had a version of a teachers union.

The idea that teachers could be part of the broader labor movement was groundbreaking at the time. But unions could not yet bargain for salaries and benefits. Membership in Local 192 was voluntary. Even at the union’s peak, only about one-tenth of Philadelphia teachers were members, says Toloudis.

In function, Local 192 was an advocacy group, but an aggressive one that drew a committed group of idealists and political outsiders.

Among its early leaders was English teacher Mary Foley Grossman — a chain-smoking intellectual who was equally fascinated with classical languages, the Philadelphia Phillies, and street protest. Even in old age, Grossman would talk about how she always attached her signs to a two-by-four “so when the fascists come, you can drop the sign on them,” said her grandson, John Grossman.

Social studies teacher Abraham Egnal and his wife, Leah, kept a mimeograph machine in their basement to print leaflets in bulk. Dinner table conversations revolved around world events, and their West Philadelphia home vibrated with political activity.

“You get this real interlace between the union, their work, [and] politics,” said their daughter, Freda Egnal. “It’s all integrated.”

Many of those drawn into Local 192’s network were children of immigrants, raised in Philadelphia’s swollen working-class neighborhoods and looking for a kind of intellectual fulfillment.

If there were an emotional current running through the early days of this union, it was one of hope and naive optimism.

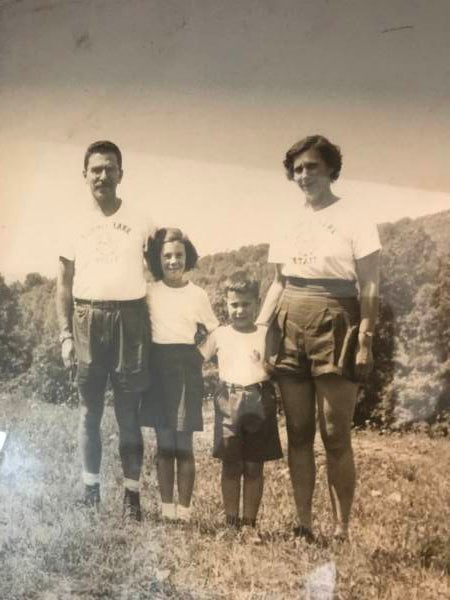

Sylvia and Sam Drasin met through the union. Or at least that’s what their son, David, assumes. They married in 1937 after a summer traveling through Europe, including the Soviet Union.

Raised in Southwest Philadelphia, Sam was the cool, quiet, chess-playing son of an unlicensed plumber who traveled the city trolleys looking for work. Sylvia was from a larger, closer-knit North Philadelphia family. She was chattier than her husband, more animated.

In politics and marriage, Sylvia and Sam found common ground. Both threw themselves into the union effort, among a constellation of other political commitments.

“They thought they were building a better world,” said David.

In 1948, Sylvia attended the national convention of the breakaway, left-wing Progressive Party, which was held in Philadelphia. Afterward, she sent an exuberant postcard to her father:

Philadelphia put on a show last night like I’ve never seen, Dad. I wish you had been there. If you love America, you would have loved it even more. For it was not cheap politicians deciding what to do with this wonderful land of ours, but the real people. I’m still thrilled. Maybe David can live in a world of peace, not war, war, and more war.

Love,

Sylvia

David was 8 when his mother wrote that letter. Today, he’s in his 80s. He reads the postcard with bittersweet wonder.

“When you read that, you feel a little sad,” said David Drasin. “But it was an exciting time for these people. I think they were proud to have been part of it.”

As members of Local 192, their combined energy was rather potent.

By 1937 — just a few years after its formation — Philadelphia’s nascent teachers union had led a successful, statewide campaign to pass Pennsylvania’s first teacher tenure law. It was an “unusually empowering” tenure law for its time, according to Toloudis.

The early success, however, proved fleeting. And the union was quickly consumed by infighting. A power struggle erupted among the left-wing activists who ran the union. Socialist-aligned teachers vied for control against their Communist-aligned peers.

This is not an FBI conspiracy or McCarthy-era propaganda. Many of the people who helped form Philadelphia’s first teachers union were also, without question, Communists.

When Local 192 formed in the mid-1930s, America’s Communist Party was on stronger footing. It was both larger and more closely allied with the rest of the nation’s political left.

That changed as the excesses and horrors of the Stalin regime grew harder to ignore — and the rivalry between the U.S. and Soviet Union escalated.

As the early 1940s dawned, the party moved further toward pariah status. While that shift played out, Philly’s “red” union became a political target.

In 1939, the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) began a two-year investigation into the leadership of the New York and Philadelphia locals. If it weren’t already clear, it became obvious to national leaders that “maybe there is an organization outside of the AFT that is controlling some of our biggest affiliates,” says Toloudis.

In 1941, the AFT ejected Local 192 from its union.

From there, the schism deepened.

The anti-Communist wing of the Philadelphia teachers union re-formed itself as Local 3, also known as the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers. That group remains the city’s main teachers union today.

Meanwhile, the Communist faction would attempt a comeback as Local 556 of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), a different umbrella union. It didn’t take. Not long after, the CIO expelled Local 556.

The Communist teachers tried to soldier on as an independent teachers union, but by the early 1950s, they’d clearly lost the war.

Soon, they’d lose much more.

As early as 1940, according to Toloudis, the FBI began to track Philadelphia teachers suspected of being Communists.

“The FBI would go through their trash sometimes,” says Toloudis. “Sometimes it would work with the Post Office to intercept mail.”

The bureau opened files on dozens of Philadelphia teachers.

No one knew, until everyone did.

Part 2: Crucible

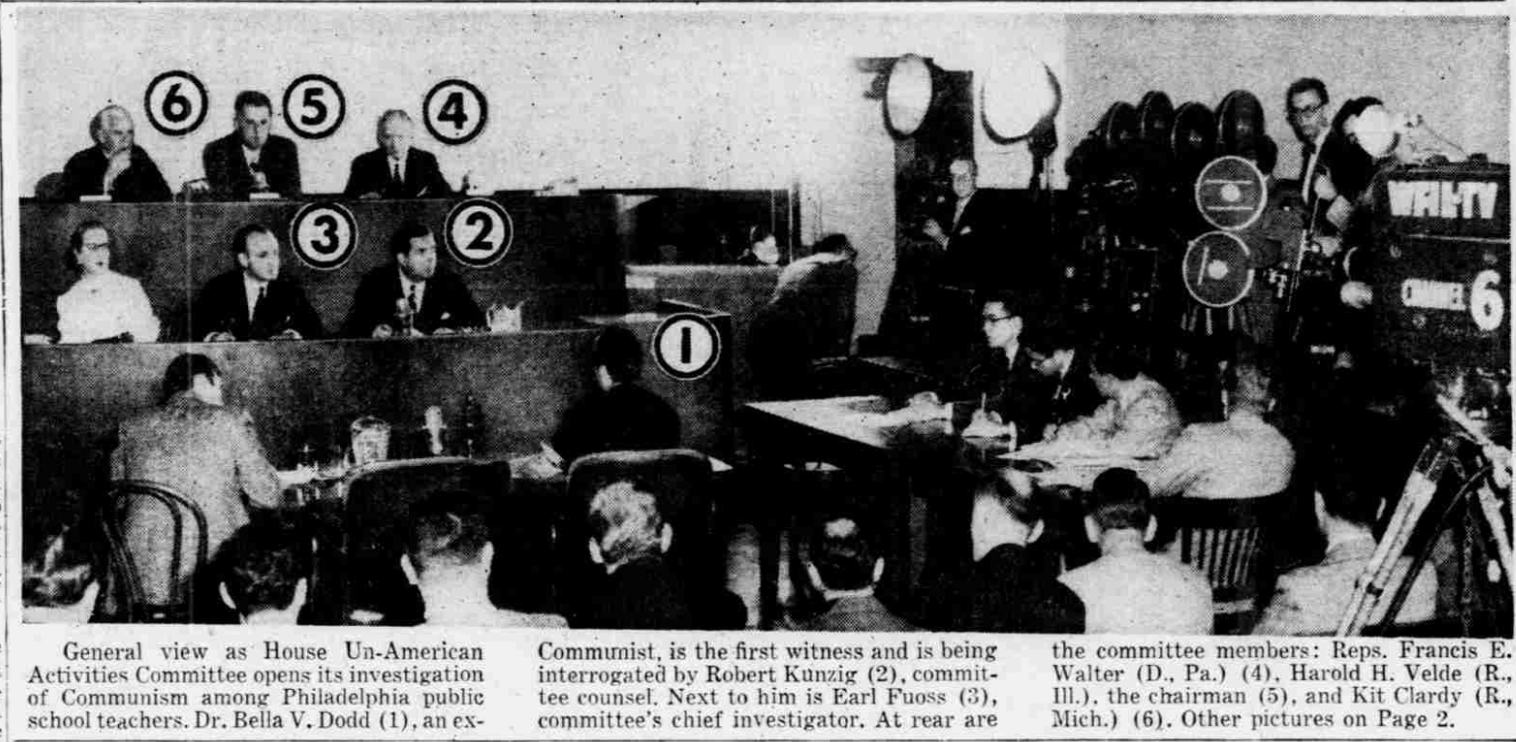

The federal courtroom was laid out in tiers.

The Congressmen filled the top row. The men in charge. The highest authority in the room.

Below them, sat the lawyers and aides. The fact-finders. The interrogators.

Finally, on the ground level, there was a small table with enough room for a microphone and a water pitcher. Behind the table, a trio of chairs for witnesses and their largely powerless attorneys.

Everything about the scene looked small, squeezed — an effect magnified by the crowd of reporters and cameras that hugged the perimeter.

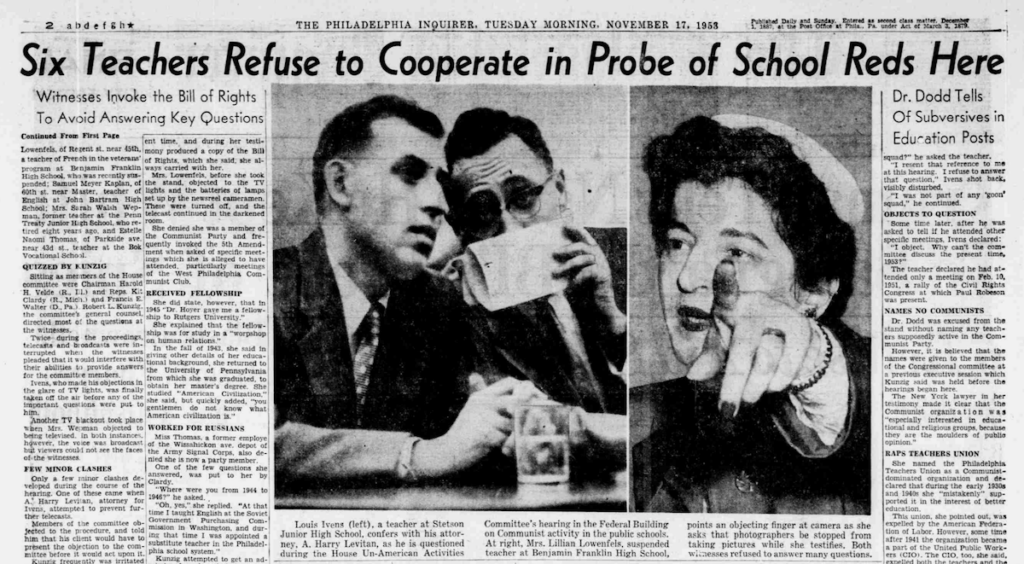

It was mid-November 1953. Congress had come to Philadelphia to find Communists.

To be more accurate, a Congressional committee had traveled to America’s third-largest city: the House Committee on Un-American Activities, commonly known as the House Un-American Activities Committee or HUAC.

During HUAC’s brief stay in Philadelphia, members spent much of their time questioning public school teachers. Over three days they called 16 teachers to testify, according to a contemporary account by the American Civil Liberties Union’s Greater Philadelphia branch. In February, at a hearing in Washington, the committee questioned another 17 Philadelphia educators.

During the 1950s Red Scare, a pair of congressional committees tried to root out Communists from organizations where they allegedly held too much influence or could pose a risk to national security. Targets included the military, Hollywood, unions, and, crucially, schools.

Why schools? Because allegedly, the Communist Party was attempting to infiltrate them.

“Those who are in touch with the rising generation are an extremely important group to them,” said Bella Dodd, the committee’s star witness in Philadelphia.

Dodd had made the journey down from New York to help HUAC solve a problem.

All of the Philadelphia teachers called before the committee had signed a mandatory Loyalty Oath in 1952 swearing they were not, currently, members of the Communist Party. There was no proof any had violated the oath.

Despite the FBI’s surveillance, there also wasn’t any proof that Philadelphia teachers had preached Communist doctrine in the classroom.

So what threat did they truly pose?

Dodd could explain.

She was herself a former teacher in New York City and a strident Communist before breaking with the party in the late 1940s. She then became an equally strident anti-Communist — someone who could expose the depth and duplicity of the Communist plot to credulous politicians.

“I don’t think the American people are aware of how deep this thing is, how all-pervasive, how it has practically permeated the very marrow of our bones,” Dodd told the audience in Philadelphia.

Dodd’s case was simple: If Communism was in a teacher’s heart, it would manifest in just about everything that teacher did inside a school. It would influence the books she recommended, the articles she emphasized — even the way she greeted children.

“The Communist teacher is very clever at putting forth her ideology and making it part of the pattern of the child’s mind,” Dodd explained.

With such dramatic statements, it’s no wonder the HUAC hearings dominated local news coverage. They were a gripping spectacle — broadcast live on television and radio.

For years, the primary record of this interrogation was a set of congressional transcripts.

That changed recently thanks to dogged research by professor Nicholas Toloudis.

He learned that Herman Beilan’s daughter, Judy Gandy, had a collection of reel-to-reels in her closet in Tucson, Arizona. Gandy didn’t know much about their origin, but she sent them along to Toloudis. Toloudis routed them to a guy in the Philly suburbs named George Blood, who revives and digitizes old audio.

The result is a remarkable piece of found history. The tapes contain only a portion of the total testimony, but what’s left has been preserved with stunning clarity. You can hear pauses and whispers — even the sound of witnesses pouring themselves glasses of water.

The testimony of the teachers reveals next to nothing about Communism. Almost all the teachers refused to answer questions about their alleged involvement with the party.

For many of the teachers, this was an exercise in containment. Speak plainly. Say little. Plead the Fifth. Go home.

But the tapes give you a sense of the emotional stakes and, at times, the fear pulsing through the witnesses.

You hear the exhausted fury of former union leader Benjamin David Anton as he wails about the “lunatics [who] have been calling me on the phone and threatening my life.”

You hear HUAC counsel Robert Kunzig ask a trembling elementary school counselor named Caroline Perloff to speak up so the microphone can capture her wispy voice.

“I do have a fairly soft voice,” Perloff replied.

You hear the way HUAC members tried to corral the conversation so that witnesses could do little else besides answer “yes” or “no” questions about their Communist pasts.

And you hear the witnesses who out-maneuvered them.

Nathan Margolis, an art teacher, tussled with the committee for over half an hour, inventing new ways to dodge questions about his Communist past.

Finally, he arrived at a chance to read a prepared statement. For whatever reason — fatigue, perhaps — the committee let him continue.

“I’m not a political theorist or a politician,” Margolis said. “I have spent 27 years of my life teaching art in the public schools of Philadelphia and elsewhere. It is my belief and understanding that a teacher and an artist has a duty of personal integrity and conscience, and that the realm of ideas is protected from invasion by the government under the First Amendment to the Constitution.”

Still no interruption. Margolis continued:

“I do not wish to be a party to a proceeding which President Truman has aptly described as lacking in American concepts of fair play and due process of law, and which is characterized by the unfounded accusation and the big lie.”

Despite his moral opposition to the hearing, Margolis was willing to make a deal. He would answer questions about his own past if the committee agreed not to ask him about anyone else.

“What is your ruling,” Margolis said to the men hovering above him.

No deal.

“We’ve given you every privilege that any witness or any person deserves before this committee,” said chairman Harold Velde, a Republican Congressman from Illinois.

Velde’s midwest baritone started to crest — a rare display of anger.

“Please show your patriotism,” Velde pleaded. “Show your love of country, if you have any.”

Part 3: The last fight

The second-to-last teacher to testify in that Philadelphia courtroom in November 1953 was Herman Aaron Beilan.

At one point, during a standard line of questioning, HUAC attorney Robert Kunzig told Beilan that the committee had “testimony” stating he’d been a Communist Party organizer in 1946 and 1947.

“Is that correct?” Kunzig asked.

Beilan — an English teacher and 23-year veteran of the school system — considered the syntax. In a droll tone, he replied:

“May I ask if you have this information, why is it relevant that you ask me?”

Judy Gandy watched her father from their home in Philadelphia’s West Oak Lane neighborhood. She was thrilled to see him on TV.

“I knew my mother was not excited,” Gandy recalled. “She was terrified.”

It had been over a year since Superintendent Hoyer first summoned Beilan to his office. Beyond this public shaming, there had been no direct consequences. All of the teachers accused of Communist ties still had jobs.

Perhaps Judy’s mom, Evelyn, sensed the sword dangling above them.

“It was not a happy time,” Gandy said. “There was a lot of tension in the house.”

HUAC had barely left town before the wheels started to move. Quickly.

Two days later — Friday, Nov. 20, 1953 — John Ehrenreich was out to dinner with his parents at Horn & Hardart, an old automat restaurant. John remembers what any 10-year-old might remember from a night out at the automat: the Salisbury steak he ordered and devoured.

His parents, Joe and Freda, likely had more on their minds. Both worked in the school system and were part of the Communist-aligned group that helped form the original Philadelphia teachers union.

When the family got back from Horn & Hardart, someone flipped on the radio.

“And I don’t know exactly what they said, but I remember one of my parents saying something like, ‘It doesn’t look good,’” John Ehrenreich recalled.

Then they heard a knock at the door. It came with a telegram for his dad, Joe. He’d been suspended from his job.

Freda had been spared. To this day, no one in the family knows why.

John remembers his dad laughing — a kind of “nervous relief.” Then he fixed himself a single drink.

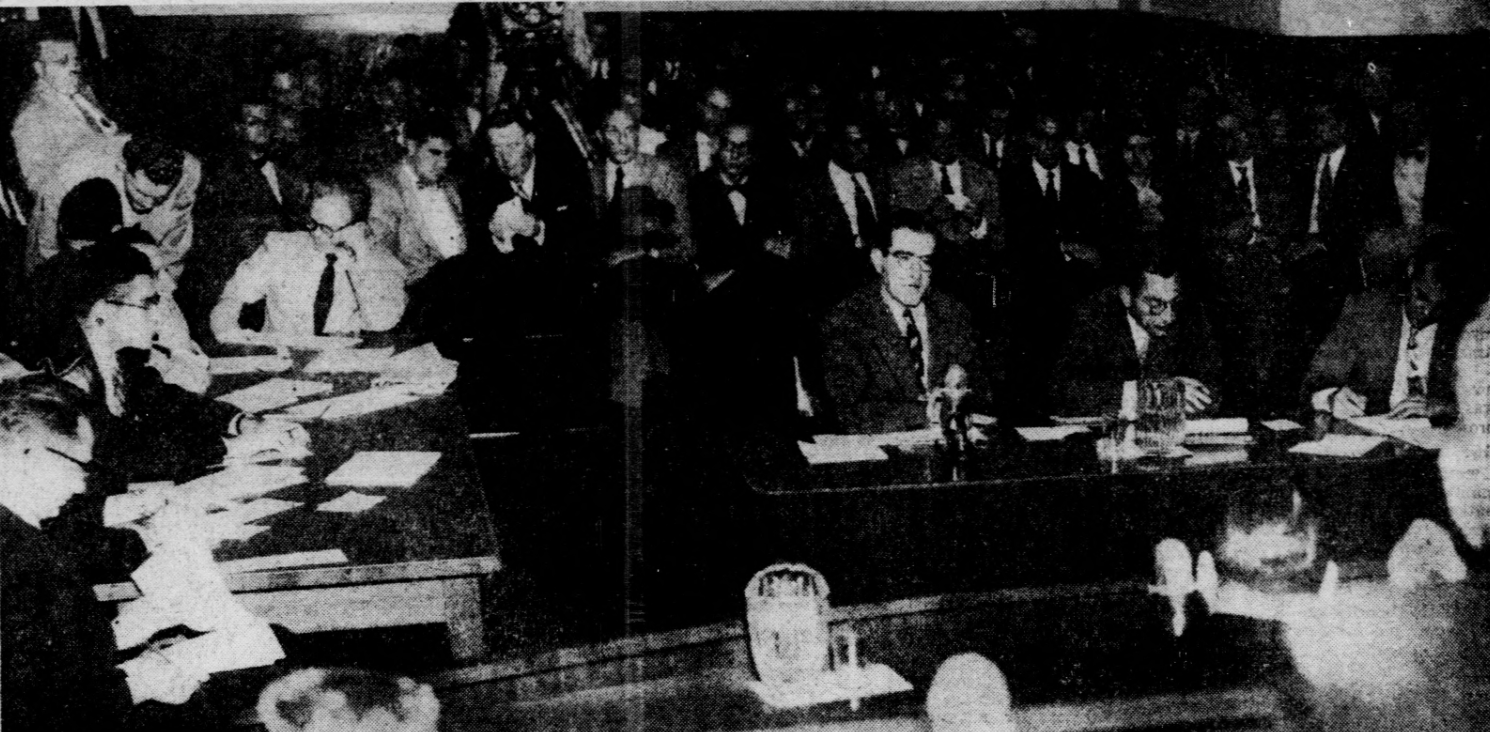

The School District of Philadelphia suspended 26 teachers that night out of an eventual 32. Some of the teachers retired or switched fields. The majority — 27 teachers — received hearings before the district’s school board in attempts to get their jobs back, according to a pamphlet published by the ACLU of Greater Philadelphia.

Over the next eight months, the school board voted to sustain each of the charges and fire the accused teachers. Most of the decisions were unanimous with the exception of school board President Walter Biddle Saul, who dissented each time, according to newspaper accounts.

Officially, the school board suspended these teachers for refusing to answer questions about organizations “whose purposes were inconsistent with the ideals to which our public schools subscribe.”

In essence, they’d been fired for not talking.

“[My father] had been teaching for 23 years and got consistently positive evaluations and had played a major role in creating the tenure laws that supposedly protected teachers,” said John Ehrenreich. “And despite those laws, they came up with a pretense to fire him.”

Many of these same teachers had indeed helped establish the concept of teacher tenure in Pennsylvania. But tenure would not save them. If anything, it created the bureaucratic mechanism to fire them.

In the early 1950s, Pennsylvania’s tenure law included a clause for incompetence. Philadelphia school officials argued that — by refusing to answer certain questions about their political affiliations — the teachers had proven themselves incompetent.

Was that legal? The fired teachers were willing to test it.

After many defeats dating back to 1941, the Communist-aligned teachers saw their latest plight as a galvanizing opportunity. They were now an independent group called simply “The Philadelphia Teachers Union.” And they tried to mount a defense in the courts of law and public opinion.

At one point, John Ehrenreich’s father, Joe, led a mission to recruit Albert Einstein to the cause. Einstein, a professor at Princeton in those years, replied with a note that was sympathetic, but unhelpful. The public, he said, already knew about his opposition to the era’s anti-Communist purges.

“I believe that it is not in the interest of the good cause if I repeat the simple truth endlessly in public and participate in the daily political controversy,” Einstein wrote to the teachers. “This would only weaken the little moral influence I am now able to exercise.”

The group pressed on. It held rallies. It published a book called “The Case Against the School Board.” And it focused considerable attention and resources on a lawsuit filed by Herman Beilan.

Beilan had sued to overturn his firing, claiming, in part, that the school district had violated his First Amendment rights. To win, Beilan would have to overcome recent precedent. In 1952, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the firing of a New York City teacher under similar circumstances.

Throughout the 1950s, the high court zig-zagged its way through a maze of free-speech cases, several of them connected to suspected Communists. The rights of public employees to political association were, at best, cloudy.

In March 1958, the court was ready to tackle that topic again in the case of Beilan v. the Board of Education.

If you’re expecting a climax here, you’ll be disappointed. Perhaps it’s a victory that Beilan’s case made it all the way to the Supreme Court.

But the case itself was a dead end.

In June of that year, the high court ruled 5-4 in favor of the School District of Philadelphia. The majority decision sidestepped the central issue of academic freedom and First Amendment rights, according to legal scholar Marjorie Heins.

Heins believes the case may simply have been the victim of bad timing.

A year earlier, the court handed down four decisions that favored Communist plaintiffs in free speech cases. Heins thinks that, after a public backlash, the court wanted to tiptoe backward.

“We were taught these notions [that] judges are neutral and they decide on neutral principles,” says Heins. “And then when you get into the trenches and you start really following history — especially this particular history, the hysteria, the Cold War hysteria that gripped the United States — you see that they flip. They come to the results based on their political feelings at the time.”

The time wasn’t right for Beilan. And the road had finally ended for the group now calling itself the Philadelphia Teachers Union. More than 20 years after it had first formed — and 17 years after it had first been tossed from a national union — the group had run out of reincarnations.

The union disappeared. Of course, the people didn’t. They had lives to lead and reinvent

“You go through this traumatic experience in ‘52, ‘53, ‘54,” said Toloudis. “And then what?”

Part 4: Rebirth

HUAC Chairman Harold Velde left Philadelphia in 1953 with an admission of defeat.

“The witnesses refused to talk,” Velde said in his closing monologue. “Instead, they say nothing. One can only draw the conclusion that, though many witnesses have emphasized that they are not today members of the Communist Party, they do not wish to help destroy the Communist conspiracy.”

With that, Velde gaveled the hearings to a close.

HUAC may not have achieved its stated goals in Philadelphia. But it had done something. It upended the lives of the teachers in its crosshairs.

The temptation here is to essentialize — to draw a clean narrative from the aftermath.

Did HUAC and the subsequent firings destroy these people? Did it stiffen their resolve?

The answer, as always, falls somewhere in between.

Life was certainly different after HUAC — at times uncomfortable or worse. Children of the fired teachers recalled play dates canceled and friendships severed in the wake of the hearings.

“I didn’t feel people hated me, but it’s clear they were very scared,” said David Drasin, whose father, Sam, was among those fired.

David’s mother, Sylvia, would’ve likely been fired, too, but she died of cancer shortly before the hearings began. The family pressed on because it had to.

For John Ehrenreich’s parents, Joe and Freda, the firings were a bump in an already bumpy road.

In the late 1940s, Joe, stricken with tuberculosis, left teaching temporarily and moved to a sanitorium. To make up for the lost income, Freda got a job as a school counselor.

Freda’s job was a lifeline for the family, but soon after the HUAC hearings she suffered a serious heart attack and had to quit. Within a year, Joe had been fired and Freda sidelined by ill health.

“We were pretty poor,” said John. “We did continue to get some help from my uncles and from some of the family friends. But things were tight.”

The scramble for jobs led the teachers in all sorts of unpredictable directions. Herman Beilan became a traveling salesman. A former teacher named William Soler worked at a dental supply firm. Another, Solomon Haas, became an exterminator. Isadore Reivich got into the dry cleaning business.

For some teachers, the events set off by the HUAC interrogation seemed to throw their lives completely off axis.

English teacher Sophie Elfont lived alone in a small apartment in Philadelphia’s Germantown neighborhood. She never married or had children. Relatives described her as exceptionally bright and caring, but not well-suited to withstand the attention that came with her firing.

Afterward, her world seemed to narrow.

“It was devastating for her,” said nephew Mark Elfont.

Another relative told me she scratched out a living working for a clipping service. She’d scour the newspaper every day, cutting out articles for a coterie of clients.

“She was able to maintain our independence, but it wasn’t easy,” her nephew said. “She certainly did not have an easy life.”

Sophie died in 1987. She was alone, Mark Elfont said — so alone that it took about two days before anyone discovered her body.

“She had dedicated her body to science, so there was no funeral,” said Mark Elfont.

There’s a pull toward the tragic here — perhaps as a way to indict the government, to prove how reckless it was in its pursuit of these teachers.

But to leave you with just those stories would be misleading. Because many of the fired teachers had rich, varied lives in the decades that followed.

Nathan Margolis’s wife, Adele, wrote several beloved books on sewing.

John Ehrenrich’s dad, Joe, had a long career as a technical writer.

The union’s last president, Francis “Fritz” Jennings, became a lauded historian.

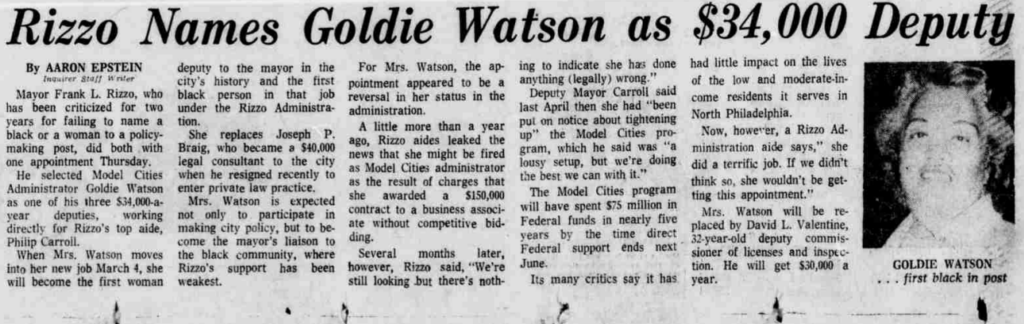

Perhaps the most interesting post-HUAC life belongs to one of the few Black teachers fired, Goldie Watson. In the years after, Watson hosted a radio show for homemakers and owned an apparel store.

She also kept a defiant foot in the political world, and worked her way back into the mainstream. In 1967, Philadelphia Mayor James Tate appointed Watson deputy commissioner of records. Shortly afterward, she became the administrator of a prominent urban revitalization program.

In the early 1970s, her political ascent culminated with an ideological twist. Conservative Philadelphia Mayor Frank Rizzo, a persistent foe of political and cultural outsiders, appointed Watson as one of his top deputies.

It’s hard to imagine that a Black former Communist would get — and take — a high-profile job in the Rizzo administration. But professor Nicholas Toloudis thinks Watson saw Rizzo much the same way she saw the Communist Party: a means to an end.

“She saw the Communist Party as being a toolbox,” said Toloudis. “The crowbars and the things in that toolbox were things she would use to pry open the segregated institutions of the United States.”

Rizzo was a very different type of toolbox, but one Watson thought she could use in her singular pursuit — a pursuit she explained to The Philadelphia Inquirer in 1974:

“If you’re trying to find out what I’m all about it’s that I decided early on in my life that I was going to use whatever talents I had to help other Black people,” Watson said.

Somewhere between the lives of Goldie Watson and Sophie Elfont, you’ll find the story of the Intille family.

Angelina Intille grew up in South Philadelphia — one of 10 children in an immigrant family from Italy. She was also the only one of those 10 to continue her education beyond high school, according to her son, Joe.

The studious Angelina fell in with a mostly Jewish group of kids from the neighborhood. Many of them went on to become teachers, Angelina included. Joe, her son, does not think his mom was an active member of the Communist Party — just that she was part of the same crowd.

Joe’s dad was decidedly not part of that crowd. He was a refinery worker with a tendency to gamble away his paycheck, Joe said. He also physically abused Angelina, according to Joe.

One day in the mid-1940s — 1946 or 1947, Joe thinks — Angelina gathered up her three boys and moved out while her husband was at work. She moved in with Bessie Stensky, another one of the Philadelphia teachers who ended up testifying before HUAC.

Joe, about 8 years old at the time, suddenly found himself in a world of school-teacher-activists.

The names splashed across the front page of the newspapers in 1953 were the people who helped raise him. People like fired teacher Eleanor Fleet and her husband, Irv — a kind of “male role model” for Joe who got him interested in science and technology.

In February 1954, Angelina Intille and her housemate, Bessie Stensky, were among the second wave of Philadelphia teachers to testify before HUAC during hearings held in Washington. Intille, like the rest of the teachers, had already been suspended from the school district. Later that year, she and the others would permanently lose their jobs.

A single parent, Intille needed work, quickly. She and a few of the other fired teachers found jobs at the Sklar School, which served students with special needs. Another group landed at a progressive independent school in the suburbs called The Miquon School.

Joe, then in high school, made a little extra money working as an exterminator for fired teacher Solomon Haas.

That pattern repeated itself. The fired teachers got jobs together. The kids of fired teachers ended up working for each other’s parents, hanging out, or even, on one occasion, going to prom together.

HUAC hadn’t blown them apart.

“It bonded them,” said Joe Intille.

Even though the union was in various states of decay, as a network of people, it remained intact — well after the Supreme Court ruled against Herman Beilan in 1958.

“To have a group like that — 50 people,” said Joe Intille. “Whoever heard of such a thing?”

As the next decade dawned, the group’s legal luck began to turn.

Angelina Intille, Goldie Watson, and two other teachers had already launched a separate challenge based on the fact that their firings had come in a slightly different order than Beilan’s.

In 1960, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled in their favor and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the appeal. Angelina was free to teach again. And she did just that.

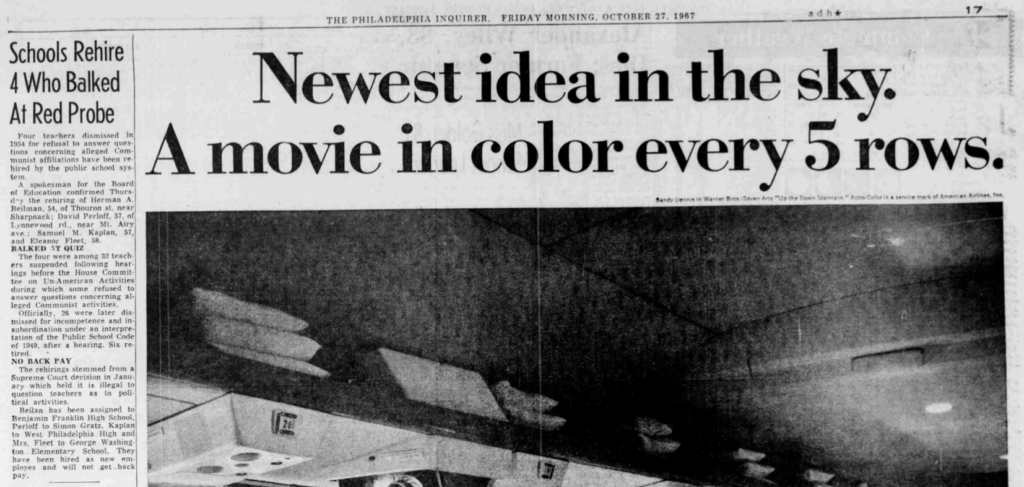

Seven years later, in 1967, the high court took up a case about a group of state university professors in New York who were fired for refusing to sign a loyalty oath. This time, the court reversed the precedent it had established in the early days of the Red Scare — all the way back in 1952.

Invoking the concept of academic freedom, the majority said the Constitution did protect teachers like the ones fired in Philadelphia.

It was close. A 5-4 decision. But it meant the saga was over.

A few months later, a tiny article ran on page 17 of The Philadelphia Inquirer: “Schools Rehire 4 Who Balked at Red Probe”

Most of the teachers had moved on. But a handful applied for reinstatement and went back to work — nearly 14 years after they’d been suspended

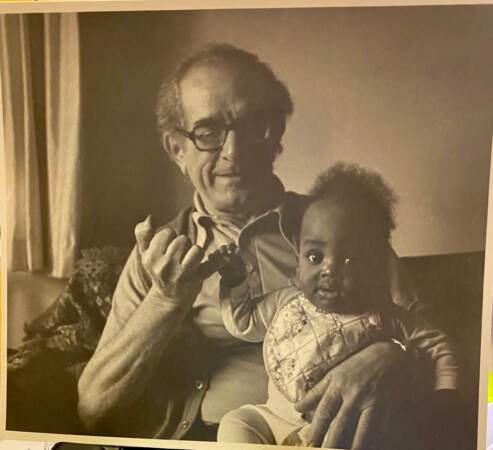

One of them was Judy Gandy’s father, Herman Beilan.

Why did he return to the school district that had so publicly fired him? Judy figures money was probably a factor. But her dad also loved teaching.

“He was completely committed to teaching. Even when he was not in the classroom,” said Judy Gandy. “He would teach me at home.”

Herman Beilan was in his late 50s by the time he resumed his public school teaching career.

Gandy remembers he would take the city bus to work every morning. And he would bring the newspaper along with him, folded up in quarters so that he could read without taking up too much room or inconveniencing the other riders.

“He was trying to occupy his brain, which is kind of standard for him,” said Gandy.

Herman Beilan and his friends were fired on the front page of the paper — and rehired on page 17.

The world had moved on. In some ways, that’s probably why they were re-hired.

By the late 1960s, there were new fronts in the culture war. As time passed, those fronts moved further and further from people like Herman Beilan.

When Beilan died in 1981, the Inquirer ran an obituary on page 31. It didn’t mention his firing or the Supreme Court case that bears his name.

Angelina Intille also finished her career as a teacher in Philadelphia’s public schools. But just because she ended up back where she started, doesn’t mean the family came through unscathed.

Her son, Joe, ended up in the Navy — stationed, of all places, in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, where his assignments had a distinctly anti-Communist flavor. When he became a civilian, Joe worked as a technical writer. In the mid-1960s, he says he took a job that required a security clearance — which the government then denied him because of his mom’s past.

The clearance denial cost Joe his job, and he ended up selling insurance for a couple of years to stay afloat. Finally, Joe says a government panel in D.C. agreed to review his case.

“They’re sitting up on this counter up there and I’m sitting down on the chair and they’re grilling me about my mother and myself,” Joe recalled. “Why should I get a clearance?”

To get his career back, he made a promise to the U.S. government.

“I had to promise them that I would not associate with my mother,” Joe said.

Joe’s older brother joined the Air Force and ended up with the same dilemma — needing a security clearance to secure a promotion. For Joe’s brother, it was a breaking point.

“It left a very bad taste in my brother’s mouth about my mom,” said Joe. “He basically held it against my mom and never forgave her.”

Even though Joe suffered the same consequences, he felt the opposite.

“I’m not ashamed of any of this, as a matter of fact, I brag about it because I was proud of my mom,” said Joe. “She stood by her principles.”

As for that promise he made to the government about cutting his mom out of his life? He never intended to keep it.

“No. No,” Joe said. My mother’s my best friend.”

Angelina eventually remarried, retired, and moved to Florida.

She died in 2004.

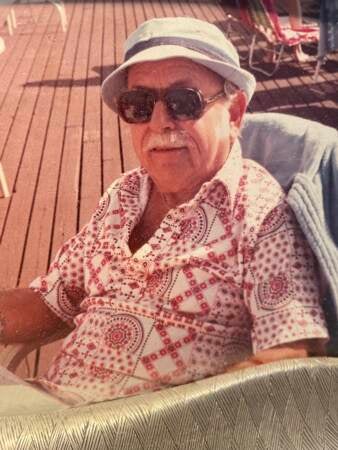

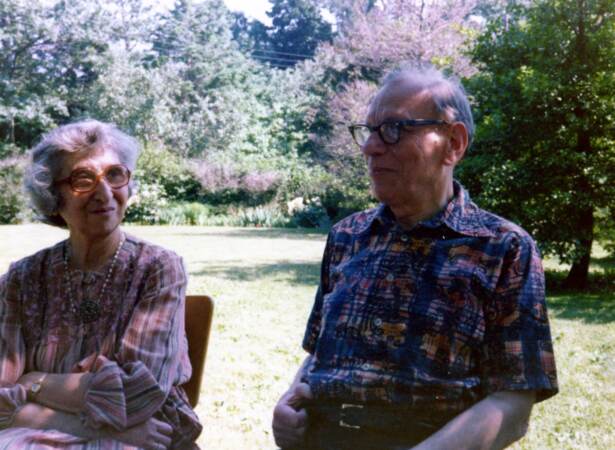

Following a generational trend, many of the teachers retired to South Florida. But in their case, it was more than mere coincidence.

“All of them all moved up to Lake Worth and they all moved into the same condo complex,” said Joe. “It was about 20 people.”

The Pine Ridge Condominium Complexes sit just southwest of Palm Beach, a sprawling patchwork of two-story buildings and man-made ponds. Pine Ridge doesn’t sound like the type of place where you’d find a group of accused Communists from Philadelphia. But in the 1980s and 1990s, you could do just that.

Alan Soler — the son of two fired teachers, William and Esther — remembers visiting his parents and chuckling to himself as they sat around the pool with their friends reminiscing about the glory days of Communism. With near unanimity, the descendants of the fired teachers say their parents and grandparents remained dedicated to left-wing causes and ideology their entire lives.

Alan found the poolside chatter amusing — and a bit hypocritical, given the material pleasures of a South Florida condo complex.

But it’s also a telling image.

Three or four decades after the government called them a threat to the nation, here they were, lounging in the Florida sun.

They’d made it through. And they’d made it through together.

Part 5: When the tape stops

In the narrow sense of legal history, Herman Beilan’s Supreme Court case was ultimately insignificant.

But if you listen to the oral argument, you will find the justices grappling with ideas that feel current — and questions that may make you uncomfortable.

For instance:

If it is indeed legal to ask a teacher about their Communist past and then fire that teacher when they refuse to answer, could a school district do the same to someone who used to be in the Progressive Party? Or the Republican Party?

“Where is the dividing line?” Chief Justice Earl Warren wondered as he grilled the school district’s attorney, C. Brewster Rhoads.

Justice Felix Frankfurter considered the opposite end of the question.

If a school district cannot fire a teacher who has been a Communist, must schools employ teachers regardless of their political affiliations?

“Would you ask him if he was a member of the Klan?” Frankfurter asked Beilan’s attorney, John Rogers Carroll.

“Under my theory, sir,” Caroll replied. “I think not.”

Today, the uneasy truce seems to be set here: A teacher can make political associations outside the classroom. As for behavior inside the classroom? The legal waters are much murkier.

“You have a right to believe and a right to belong,” says Julie Underwood, former general counsel for the National School Boards Association and an expert on education law.

Those rights have come and gone over the years. In many ways, we’re still dancing around a fault line that has run through the teaching profession — and American society — for over a century.

In June 1917, 35 years before Herman Beilan was summoned to the superintendent’s office, The Philadelphia Inquirer ran an alarming headline: “Disloyalty Found in Public Schools.”

Months earlier, the U.S. had entered World War I. The hunt was already on for subversive teachers.

The school district discovered 47 “aliens” working in city classrooms and said they would all be fired unless they declared their intention to become citizens. What’s more, the Inquirer reported, “the failure or refusal of any teacher to stand up for the American Flag and cause … will be ground for punishment by instant dismissal.”

In January 1942, a HUAC predecessor called the Dies Committee summoned its first Philadelphia teacher to testify — a woman named Bessie Burchett.

The U.S. had recently entered World War II, and Burchett was a Nazi sympathizer who’d spent years railing against textbooks, left-wing teachers, and what she considered the Communist threat to Philadelphia’s public schools. Prior to her appearance before the Committee, and after years of erratic behavior, Burchett was forced out of the Philadelphia school system.

By the time the 1950s arrived, it was a well-established truth: In times of national insecurity, teachers were a target.

“People fear the indoctrination of their children,” says Underwood. “[Parents] don’t want their children to hear something, learn something, do something that they have no control over or have little control over — or that they don’t understand or that they disagree with.”

By the late 1960s, there had been some acknowledgment — both by society and the country’s highest court — that the pursuit of heretical teachers had gone too far. The cost was too high, the reward too low, and the pursuit itself too antithetical to the tenets of free speech.

“The nation had shifted,” says Underwood.”The question is when and if the nation will shift back.”

Today, schools find themselves at the epicenter of another culture war and another debate over the political expression of teachers. As of now, the debate revolves around what those teachers do inside the classroom.

Could it venture beyond that? Clearly, it can.

In this context, why should we retell the story of 32 Philadelphia teachers suspended from their jobs in 1953?

“Historical memory is important,” says John Ehrenreich, son of fired teacher Joe Ehrenreich. “I think that in many ways, Americans are cut off from their own history.”

You may recognize the names of some of the school board members who actually fired these teachers — Joseph Greenberg, William Loesche, J. Harry LaBrum. They all had schools named after them in Philadelphia.

So maybe there’s virtue in the retelling itself — if only to even the score a bit in terms of public memory.

But the fact that these Philadelphia teachers were fired for their political associations should also tell us something about ourselves.

It speaks to our sensitivity around public education — what Professor Nicholas Touloudis calls the “very genuine fears” that this vital institution can be corrupted.

In this nation, we don’t have a common skin tone or a common religion. If we have anything in common, it’s a civic religion. You aren’t born into that. You have to be taught — probably in a school.

Teachers, explains Toloudis, “are doing the work to inculcate Americanism.”

Sounds like important work, right? And it seems that you might scrutinize the person doing this work — this inculcation — whenever you feel some aspect of Americanism eroding.

That impulse to scrutinize can lead to some dark places. If nothing else, it’s worth sitting with that thought.

“It has value if people are reminded,” says Herman Beilan’s daughter, Judy Gandy. “[But] if you are reminded and you do nothing, then what’s the point?”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.