Don’t eat the marshmallow: Students from a ‘no excuses’ charter grow up to tell the tale

"If you actually said, 'We’re gonna hold you accountable to setting up your students for life.' Then how does that change the work of that school?”

Jayuana Bullard sat upright on her bed — in a room wallpapered with lipstick imprints, in a house crumbling from neglect, in a neighborhood known as one of Philadelphia’s most violent.

The thought came easily, like she’d summoned it before.

“I wonder if they felt like they failed somehow,” she said.

They were her teachers from a middle school she’d left more than a decade ago. She not only remembered them, she wanted their approval. Still. All these years later.

“Sometimes I think about it,” she said. “And I wonder.”

Jayuana is 25, an age when middle school is often a distant memory. We may be able to name a teacher or class that still resonates. Perhaps we had some social awakening as we passed from childhood to adolescence.

Few of us probably see our lives as a referendum on the people that taught us in middle school.

Not Jayuana.

“As far as my character, as far as me figuring out how to get things done and figuring out how to treat people on a daily basis…Me as a human?” she said. “They played such a big role.”

There’s not a statistic, a data point, a concrete, measurable outcome in Jayuana’s life that would lead you to this conclusion.

But, when you talk to Jayuana and hear the plain conviction in her voice — you know it.

So what was this school?

It was one of Philadelphia’s first ‘no excuses’ charter schools. And the students were like guinea pigs in an intense educational experiment, one designed to alter lives and, crucially, measure whether it worked.

A dozen years after the school’s first class graduated eighth grade, the students are now in their mid 20s. We caught up with Jayuana and 32 of her former classmates. Some who made it to graduation, some who didn’t. Some who praise the school, others who abhor it.

But we were most interested in the people themselves.

What happened to them? Can middle school really change a person’s life? What would lead a person like Jayuana to say:

“I know for a fact that if I went to a different school, I wouldn’t be the same person I am today.”

This story was produced as part of WHYY’s Schooled podcast. You can listen above, or subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

‘Wanna learn about a new school?’

It’s been 16 years since Marc Mannella — a self-described “27-year-old white guy” — walked around North Philadelphia with a polo shirt, a clipboard, and a promise.

He needed 90 rising fifth graders to sign up for the middle school he was opening in an abandoned recreation center at 8th and Cumberland Streets.

His strategy: post up outside grocery stores, hang flyers in windows, and approach groups of children on local playgrounds.

“Do you wanna learn about a new school,” he’d ask them. “Take me to your mom.”

When he found parents, his pitch was simple — hinged on a distant reward.

“There was an element of faith involved,” Mannella said. “Like we believe that if we do X, Y and Z, then 15 years later, there will be this pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. And that pot of gold was a college degree.”

We often judge schools based on one-year of data, typically tied to test scores. Sometimes we look at four-year marks, or, if we’re really stretching, six. From this jumble of numbers we extract conclusions about whether a school does right or wrong by its students.

Mannella and his team had a longer horizon in mind.

How do you set your students up for life?

Most stories about a middle school would be about what happened in middle school. This story is different.

It’s about the things students carry with them years later. It’s about a school rooted in a deeper promise: to forever make students’ lives better.

It may seem crazy to judge a school based on what happens years and years down the road. But that was the point, to rethink the purpose of education.

“If you actually said, ‘We’re gonna hold you accountable to setting up your students for life,'” said Manella. “Then how does that change the work of that school?”

***

For this project, we interviewed 33 members from the inaugural class of KIPP Philadelphia.

The alumni are 25- and 26-years old now, about the same age as Marc Mannella in the spring of 2002.

Back then, Mannella was finishing up his fourth year as a classroom teacher — two in a traditional public school and two in a North Philadelphia charter school. He loved his kids, but felt his schools gave up on them too easily.

That spring, Mannella spoke on a panel of Teach for America alum. One of his co-panelists, Mike Feinberg, had founded a charter school eight years earlier in Houston.

The school was called KIPP — short for the Knowledge is Power Program.

Buoyed by impressive student test scores and glowing press, the charter school had recently expanded to New York, DC, and rural North Carolina. 60 Minutes correspondent Mike Wallace claimed in a 1999 profile that KIPP’s success proved “children from poor, minority neighborhoods can perform every bit as well as the most privileged middle school students across America.”

KIPP seemed both old school and radical. Kids learned through repetitive drilling and chants. School days lasted 10 hours. The school year began in mid-Summer. And if students stepped out of line — even a little — teachers came down hard.

Schools like KIPP would become known as “no excuses” charter schools. In time, this model would spread across the country.

Marc Mannella hadn’t heard of KIPP before that panel in 2002. He was blown away after watching the 60 Minutes piece and asked Feinberg afterward when the organization might open a school in Philly. He’d love to teach there.

“He said, ‘I’ve been listening to you on this panel. We’ll open KIPP in Philly as soon as you’re ready to open it,’” Mannella said.

It sounded crazy to Mannella who had, again, only been a teacher for four years.

But these were the early days of the charter school movement. And like the early days of any industry, there were quick paths to the top for people with the luck to find them and the drive to follow them.

KIPP whisked Mannella away to a fellowship bankrolled by the founders of the Gap clothing empire where he got a crash course in running a school.

In April 2003, less than a year after that panel, Philadelphia gave Mannella and his team the green light.

And on July 14th, 2003, 90 fifth-graders filed into Hartranft Rec. Center.

Inside, on white board, was the drawing of a mountain with a flag planted on top.

“And the flag said 2011,” Mannella recalled. “2011 was the year they would go to college.”

The school’s goal was to turn these 90 fifth-graders into college graduates. They’d have four years to prepare them for the journey up that mountain — and a decade more to see if the students would reach the summit.

‘A better tomorrow’

If the white board wasn’t a clear enough indication of KIPP’s drum-beat focus on the future, the students would soon get an audio aid.

In typical KIPP fashion, it was a chant — one that former student Christopher Johnson remembers learning on the first day.

These are the kids / that want to learn / to read more books / to build a better tomorrow

“It was early in the morning,” Johnson said with a laugh. “We were like, ‘Why are we yelling about building a better tomorrow?’”

And there was one more curiosity: Their school had no chairs.

Try to imagine. You’re 10 years old. You show up to a totally new school. There’s a mountain on a white board. You’re chanting about the future. And you’re doing all this on the floor.

“That was just confusing,” Johnson said. “Like, ‘What are we doing?’”

KIPP actually had chairs, but students had to earn them. Students had to behave. They had to follow the rules.

They learned from this early moment they were entering a world built on incentives.

“You have kids for whom school isn’t working,” Mannella said. “And so how are you going to structure a system to sort of change the decisions that kids make all throughout their day?”

KIPP’s answer was to turn school almost into a job.

Students got paychecks every week based on their behavior. Finish your homework, help a classmate — you get something called a KIPP dollar. Talk out of turn, chew gum, leave your shirt untucked — lose a KIPP dollar.

Students who finished the week above a certain dollar threshold went to a party. At the end of the year, the well-behaved students went on a big, out-of-town trip.

But with the carrot came a stick, a punishment for students who didn’t earn the requisite KIPP dollars.

And if KIPP’s goal was to make sure those 90 students made it to and through college, that stick is very important to understand.

It was known as the Personal Improvement Plan. Everyone called it PIP.

If the flag on the mountain represented the goal, PIP was the footpath at the base. It was a punishment system designed to keep kids on the climb, to build the habits of a student who could prosper in life.

But it was also kind of extreme.

PIP students sat in a separate part of the classroom, in smaller, less comfortable chairs than everyone else. They had to write letters of apology based on whatever infractions got them on PIP — reminiscent of Bart Simpson standing at the chalkboard after school.

Students on PIP also had to wear a yellow shirt over their school uniforms. Lots of the students we interviewed had strong reactions to the memory of these shirts — they did not, apparently, smell good.

“Why are these kids sitting on crates with dirty yellow shirts? This is weird.” — Jayuana Bullard

“I might have had, you know, somebody’s shirt from the day before — who forgot to put deodorant on. We’re growing boys! Now I’m sitting here smelling musty. You know it was just a lot. It was mentally a lot.” — Jesse Oyola

“You can’t wear your KIPP t-shirt anymore because you were stripped of that right. You wasn’t a KIPPster, you’re a PIPster.” — Shakoor Sanders

“You couldn’t hide from it. You wore this bright yellow shirt. Sometimes there were stains on it. Sometimes they stunk, I’m not gonna lie.” — Zuleika Roman

PIP students couldn’t talk to other students for any non-academic reason — not in the hall, not in class, not at lunch. That particular punishment, Mannella said, was “like hell on earth for an 11-year-old.”

Underlying PIP was a harsh premise.

KIPP leadership felt, in Mannella’s words, it was “OK for us to admit that we weren’t equipped to handle some of the students who had the toughest, toughest behavioral challenges.”

That meant students who regularly ended up on PIP — or chafed at KIPP’s intensity — often ended up leaving the school.

Of the 90 students who showed up on the first day of school, ten were gone by mid-November. As the months went by, enrollment kept dropping. Mannella estimates the school lost 25 students in its first year.

Sometimes, a parent would say, ‘I’m sick of this intense school. It’s not working. I’m pulling my kid out.’ And Mannella wouldn’t fight them.

Other times, Mannella would sit the parents down and suggest the child leave.

“We started the school thinking, ‘KIPP is an opportunity, KIPP is a privilege,’” Mannella said. “And if students can’t thrive in this environment — and if they choose to leave or frankly if they just can’t get it right — I’m going to look at the mom and I’m gonna say, ‘Mom, it’s time to go.’”

‘Against my human rights’

When a discipline system works, it can change how a person thinks, what kind of incentives they respond to.

When it doesn’t, it can convince someone they’re never going to change.

Zuleika Roman could have gone either direction.

Days before Zuleik was born, her mom sat in a courtroom and watched her dad receive a 6-to-15 year sentence for shooting a man in a neighborhood dispute. His absence framed Zuleika’s early years in North Philadelphia, seeding a stubbornness that would sometimes manifest as anger in the classroom.

She carried that anger from her district-run elementary school in North Philadelphia to KIPP. Zuleika was small but feisty — a student who talked back to teachers and lashed out at classmates.

“I spit on a child for her saying something to me that I didn’t like,” Zuleika remembered. “I think we were arguing beforehand and she called me ‘a bitch’ and that’s what I did.”

KIPP’s punishments didn’t bother Zuleika. She didn’t care about the stinky yellow shirt or the social isolation.

But not getting those rewards started to sting. She hated that she didn’t get to join the weekly celebrations or go on the first year-end trip.

“And so then I started working for money,” she recalled with a laugh.

Zuleika wasn’t the top performing kid. She knows that. But she’d been rewired, her circuitry shaped by this careful system of rewards and punishments.

In 7th grade, Manella chose Zuleika to represent KIPP Philly at a national conference in Texas. She beamed.

“I felt a lot of pride in that,” Zuleika said. “And I think that’s when I was like, I really love this school.”

Compared to Zuleika Roman, Jesse Oyola seemed like he would flourish in school.

He grew up in North Philadelphia with two teachers for parents. They put a lot of emphasis on education and sent Jesse to a Catholic elementary school.

But it started to wear on him. He was a hyperactive kid and that didn’t mesh with the orderly vibe. Jesse’s mom thought KIPP would straighten him out.

Jesse thought it might help, too — that is until he got there and saw the laundry list of things KIPP forbade.

“It’s like, ‘OK, wait a minute. I’m going to do six of these items like first week,’” he said.

Jesse ended up on PIP, constantly.

Instead of buying into the system, he obsessed over its excesses. If he did something relatively harmless and lost KIPP dollars, it pissed him off more. He was a perceptive kid. He understood the logic behind PIP, but that knowledge only fed his insubordination. Jesse didn’t want to be rewired.

“I’m just like, ‘That makes absolutely no sense to me at all,’” he said. “‘This is, like, against my human rights’ — like, I was that kind of kid.”

The incentive system at KIPP was supposed to create a positive feedback loop. For Jesse, it did the opposite. He gave up.

He accepted the yellow shirt and, in time, came to see himself as “bad.”

“If anything it made me more angry with myself, with those around me and I kind of carried that stigma going forward,” Jesse said. “Because then I was just like, ‘Well I didn’t do good here so I’m not going to do good anywhere. It doesn’t matter what I do.’”

Jesse compared PIP to prison — even solitary confinement. He wasn’t the only former student to draw that comparison. Even some students who adored KIPP worried about the effect of its discipline system on classmates. They wondered: Does constant policing of small infractions begin to change how a student views him or herself?

“If you criminalize something, then people start to believe that they’re criminals,” said Christopher Johnson, a KIPP superstar who flourished at the school and was, when the reporting for this story began, a KIPP Philadelphia spokesman.

KIPP Philadelphia later abolished PIP after a teacher told Mannella it resembled incarceration — right down to the racial dynamics of mostly white teachers placing bright, uniformed clothing on black and hispanic students. The school now loses significantly fewer students each year and works to fill the spots of students who leave.

Those changes came too late for Jesse Oyola.

When sixth-grade ended, Jesse, his parents, and Mannella had a conversation — the conversation.

“We had a meeting,” Jesse remembered. “Principal Mannella was like, ‘Hey, this is a mutual thing, like, this isn’t working.’ My mom and dad were like, ‘Yeah, this obviously isn’t working.”

Of the 90 students who enrolled in KIPP Philly’s first middle school class, about half were boys. By the time 8th grade graduation arrived, enrollment was whittled down to 34 students — and only 11 boys remained.

That didn’t surprise Jesse. He thought other boys at KIPP reacted the same way he did. They toughened up when the school cracked down.

“It’s like, ‘I can’t show I’m vulnerable,’” he said.

There were lots of kids like Jesse — kids who couldn’t handle KIPP, or kids that KIPP couldn’t handle.

And so before KIPP students could ever get to the world beyond middle school, many of them were gone — casualties of the very system that was supposed to lift them up.

***

Jesse’s journey through school remained bumpy after leaving KIPP.

He bounced through three other charter schools before getting expelled from the last one. He eventually got his diploma at a cyber charter, the one school where he felt he had the breathing room to be himself. After a party-filled year at college he dropped out and enlisted in the National Guard.

He now has four kids and works as a line cook in Lancaster, Pennsylvania — about 90 minutes west of Philadelphia. He’s passionate about what he does, and hopes to start a program where he teaches cooking to under-privileged kids.

KIPP did not derail him completely, but it left a bitter taste. He’s thankful he got out when he did.

“I think I kind of got out in time before it made me a completely different person,” said Jesse, 26.

We learned the names of almost every student who entered KIPP in 2003. Of those, we came across no dramatic stories of lives crushed by KIPP’s disciplinary focus and didn’t find any former students who are currently in prison.

There was at least one former student who seemed lost to “the streets,” as one of his former classmates put it, but he never returned inquiries for an interview.

We did, though, find kids like Jesse — kids who felt stifled by PIP, or worse.

As former student Shakoor Sanders, 26, put it, “It was brainwashing.”

It wasn’t the type of brainwashing that prevented Shakoor from becoming a jazz percussionist, a talent nurtured by one of his KIPP teachers. But it was the kind of discipline that stuck with kids.

“It’s like the army, man.” Shakoor said. “You leave out a totally different person.”

‘Crazy in a good way’

In theory, KIPP’s discipline system was built in service of academics.

And to a student like Deena Swann, that’s exactly what it was.

Deena, now 26, entered KIPP testing in the third percentile in math. In other words, 97 percent of kids her age tested better. Her reading scores weren’t much better. The lessons at her North Philadelphia elementary school so baffled her, at times, they might as well have been in Spanish.

“That’s how foreign everything was to me,” she said.

Deena rarely called attention to her confusion. There always seemed to be higher priorities: a troublemaker to subdue or a fight to quell. Besides, it wasn’t in her nature to speak up.

KIPP’s strategy started with a basic assumption that its students were like Deena — behind and under-taught. Students showed up in summer and pulled 10-hour days, all in the name of catching up.

“I can’t explain it any more than like a boot camp — like, ‘Ok, break you down, build you up, get you ready for this journey,’” Deena said.

Classes could even feel militaristic — math class in particular.

KIPP would teach kids chants and songs to help them learn multiplication or memorize formulas. In KIPP parlance, this was called “rolling your numbers.” A surprising amount of students still use the songs to solve multiplication problems today. One, a convenience store manager, said it is vital to his job performance.

The military style, though, didn’t necessarily feel oppressive. Lots of the students remembered classes fondly, math classes in particular. The KIPP classroom, students said, had a buzz they’d never felt.

“It was crazy,” remembered Markesha Burnett. “But it was crazy in a good way.”

The chants weren’t just energy for energy’s sake. The memory devices allowed the kids to feel like they were mastering something. For a kid like Deena — lost in her old school — success created its own momentum.

“I remember being so excited, like, ‘I know every answer!’” Deena said.

PIP was only a part of Deena’s story insomuch as it created an orderly environment where she could learn.

She was rarely on PIP herself, but, “We knew that, ok, if you do this, there’s going to be a consequence,” she said. “Johnny’s not going to kick me and get away with it.”

Deena didn’t merely get back on track, she started speeding down it. By the beginning of seventh grade, Deena tested in the 91st percentile for math.

It was an academic miracle.

***

At most schools, the story ends here. You prepare kids for life beyond. You lose touch. And you assume that if you did your job, things will generally work out.

The 34 kids who made it through KIPP and graduated eighth grade in 2007 seemed to be well on their way. Marc Mannella was supremely confident about their prospects.

“When they left us in eighth grade they were ready to take on the world,” Mannella said. “One hundred percent of them believed that they were going to go to and through college. And then life happens. Right?”

Life happens.

The real question for a school like KIPP — a school premised on larger life outcomes — is what from the classroom will really stick? Mastery of middle school math? Inspirational chants? PIP?

Would any of it matter in the long run?

Embarrassed and ashamed

After being one of the featured speakers at eighth-grade graduation, Deena Swann enrolled at Cardinal Dougherty, a Catholic high school in North Philadelphia.

Things went sideways — fast.

Deena says it wasn’t any one thing. She just started coming to school late, tiptoeing into some of the freedoms she didn’t have at KIPP.

“I think I got a taste of that freedom and was like, ‘Oh, ok, I think I’ll stop at the store before I go to school,’” she said.

KIPP was great for Deena while she was there. When she left it became pretty clear, it had also been a crutch.

She and her mom recalled one Monday during middle school when Deena wasn’t planning to attend school. The weekend had been tumultuous, punctuated by an argument between Deena’s mom and her then-partner.

Someone from KIPP called to ask about Deena’s whereabouts, and then sent a cab to ferry her to school.

“KIPP micromanaged everything,” Deena said. “Like, you know, if I wasn’t in school, ‘Why isn’t she in school? She needs to be here.’ They brought a lot of stability to my life.”

Deena spiraled when that stability evaporated.

She left Dougherty in 10th grade after piling up infractions for repeated tardiness. In 11th grade, she moved to South Carolina with relatives. She says her mom pretty much let her do as she pleased.

Deena moved back to Philadelphia shortly before senior year began, and had a short fling with a guy. It was, in her words, a typical high school relationship.

Deena didn’t realize she was pregnant until after the pair broke up.

“It was definitely scary, really scary,” she said.

Deena got a job at a clothing store, and was able to finish high school after having her son, Brandon.

She tried briefly to attend Community College, but says she wasn’t ready for the responsibility.

“I remember almost being, like, embarrassed and, you know, ashamed of the route that I was taking,” she said.

Almost none of the KIPP alumni we interviewed did four years at one high school followed by four years at one college. All of them seemed to flounder or grow restless or get sidetracked somewhere along the journey up that mountain.

KIPP propelled them to high school — usually a Catholic school or a private school or a magnet school — but they didn’t stick there. KIPP’s lessons didn’t always follow them out the door.

***

KIPP, though, actually had a plan for these pitfalls.

Her name was Susan Larson.

Raised in rural Maryland, Larson signed on as one of KIPP Philadelphia’s original teachers. She figured her North Philadelphia experience would be a pitstop on the way to some suburban school district. She’d do a little good, and get out.

She stayed mostly because of her relationships with the students, a mix of affection and obligation. Those relationships only deepened when Larson moved into a new role — the kind of position that only exists when a school has its eye on the long view.

Larson’s job was to keep tabs on KIPP’s graduates as they headed off to high school and beyond. Her goal was clear: keep students on track for that college degree.

“We were very college, college, college, college, college,” she said.

Larson could have viewed herself a one-woman net. If kids fell off the narrow, perilous path to college, she’d catch them. But she says she never saw it that way. She helped kids up when they wanted it, but she wasn’t there to stop them from falling.

“If we completely spend our lives, KIPP spends their lives, trying to prevent them from falling, they’re not going to learn any lessons,” Larson said.

Had Susan approached this task any other way, she probably would have driven herself crazy. Because more big falls were coming.

Some of those falls seemed to be a byproduct of the KIPP experience, the way it prepared or didn’t prepare students for the responsibilities they’d face after middle school.

But sometimes, as Marc Mannella put it, life happens.

For Zuleika Roman, high school went fairly well until her senior year. She failed a math course required for graduation, and could have made that course up in the summer.

Her father, then back from prison, wouldn’t allow it.

“He wanted me in the house,” she said.

Zuleika returned for a second senior year and graduated. Shortly afterward, her dad left for a trucking job in North Dakota.

That’s when Zuleika went to the police.

She told authorities her dad had been sexually abusing her since she was 14. It started as inappropriate touching, but escalated. Multiple times a week — when family members were asleep or away — he would give her drugs and alcohol before forcing himself on her.

“I was scared,” she said. “My situation wasn’t handled until I was in college. When I broke away from there, I told my mom everything and we followed that process.”

Zuleika’s dad eventually pled guilty to rape.

By that time, Zuleika had graduated from high school. She kept in touch with KIPP teachers, but never told them why she repeated her senior year.

“I just remember them telling me that their door was always open, and, if I needed help, to call them at any time,” she said.

Zuleika made it to college, a school called Cabrini just outside Philadelphia. There she reconnected with Jesse Oyola.

Zuleika and Jesse had polar opposite experiences at KIPP. Zuleika bought in to the school’s incentive-driven discipline system. Jesse hated it.

But their roads converged in the same place after high school, and they had surprisingly similar experiences.

Both spent one year floundering amid outside distractions and newfound freedoms. They partied, procrastinated and eventually peaced out: a familiar sequence for wayward freshmen.

Zuleika, theoretically, had a leg up on Jesse. She had Susan Larson checking up on her. So why didn’t that work?

It sounds counter-intuitive, but Zuleika thinks it’s because she loved her former teacher too much.

“When you’re looking for approval from somebody you don’t want to tell them the bad things,” she said. “You only want them to be proud of you.”

Through her first and only year at college, Zuleika told Larson everything was fine. She didn’t tell Larson she was dealing with the aftermath of her sexual assault or that she was failing a course.

“I definitely didn’t tell her that I was going to a dorm party instead of doing my homework and then doing my homework at 3 o’clock in the morning on Adderall when I had a class at 7 a.m.,” Zuleika said. “So things like that I kept out.”

Zuleika was hardly alone. Lots of KIPP students stumbled at college.

Larson remembers students who felt isolated or unprepared — and it wasn’t always related to academics. Sometimes students seemed unable or incapable of living on their own. She’d show up on campus and realize students didn’t have food. She’d treat them to a meal and try to connect them to help.

That was the strategy: to show up, to be there, to drop a line.

But sometimes students simply drifted out of range.

When Zuleika Roman dropped out of college she met a guy with a silver Ford Mustang and a penchant for adventure. They both wanted to get away. So they vanished on a six-month road trip.

“That was kind of my way of, like, freeing myself from all the crap that was happening at home and all the stuff that I failed at,” Zuleika said. “’Yeah, sure, let’s travel and just do whatever.’”

When Zuleika and the guy broke it off, she came home to a pissed-off mom and a bunch of Facebook messages from Susan Larson. They weren’t profound notes — just little nudges and check-ins.

“Hey, what’s going on?”

“Haven’t talked to you guys in a while.”

“Miss you.”

To Zuleika, the words meant less than the fact that Susan Larson had sent them.

“It’s like, that was my life raft,” she said.

It ended up being the most important part of her KIPP experience.

Zuleika re-enrolled in college, with Larson helping her apply for financial aid. She earned her bachelor’s degree this spring and now works at a pre-school in North Philadelphia.

KIPP changed Zuleika while she was there — from rebellious kid to proud student.

But she doesn’t think those four years mattered as much in the long run as the years that followed.

“KIPP is the only school that I tell people, ’Yeah, my teachers were there with me through high school, through college, and even now getting my bachelor’s degree, she still messages me,’” Zuleika said. “And they’re like, ‘What, your middle school?’ ‘Yeah, my middle school.’”

‘To have seen different’

On a recent March morning in Philadelphia, Deena Swann walked down a North Philadelphia street hand-in-hand with her eight-year-old son Brandon.

Across the street, a featureless brick facade cast morning shadows on the sidewalk. The wall belonged to a middle school, the one Deena would have attended had she not gone to KIPP.

Its presence was symbolic, but coincidental.

Deena headed into A-Plus Academy, a preschool located across the street. It was her first day as director.

It would have been hard to imagine Deena here eight years earlier — when she was a teen mom trying to get her diploma.

Deena had been a star at KIPP, an academic miracle story. Then high school hit, and the miracle looked more like an illusion.

So did KIPP help her ace a few tests in middle school? Or did it actually change her life?

Deena believes the latter, but not primarily because of what she learned in those frenetic four years. Or at least not because of the academics she mastered. Instead, it was something else that stuck.

“Even though I was doing things that I should not have been doing, I always kept KIPP in the back of my mind,” she said.

Deena went straight to work out of high school. She’s worked at gas stations, pharmacies, and a mental health clinic. She had a second child at 21.

There was no dramatic moment where she pivoted back to college. But, when life settled down, she thought about it again, and, in particular, a two-year school called Harcum College.

Susan Larson told her the school would be a good fit because of its night classes. Deena enrolled in 2015, the same year she was originally supposed to earn her bachelor’s. Last spring, she graduated with an associate’s degree.

Deena believes some day she’ll go back for her bachelor’s. Ask why and she talks about something she learned at KIPP — or to borrow her word, something KIPP “installed” in her.

“You know nothing is ever forever,” she said. “So if you’re doing this right now or you had these experiences you can change them. Like you don’t, I don’t have to continue in this direction, in this path.”

Deena explained this while sitting in the same North Philadelphia rowhouse where her mom raised her — and where her mom also grew up.

Three generations of Swann women have called this place home. And now Deena is raising her boys in the same place. Her plaque for “KIPPster of the Year” — an award she earned in 7th grade — sits in a cabinet next to the dining room table.

Her surroundings looked frozen in time. But when Deena spoke, she talked like someone who’d been transformed — someone aware of possibilities that her mother, living within the same walls, couldn’t have fathomed at her age.

“I don’t know how to explain it,” said Deena. “I guess if you don’t know then that’s one thing. But when you do know then, it’s different.”

It’s different.

There is almost no way to measure this — no moment to point to, no curriculum to copy. KIPP planted something in Deena’s brain, a seed that sat in the ground for years until, one day, it sprouted. Somewhere between the mountain on the white board and graduation she absorbed the idea that she was bound for greater things.

“If I hadn’t had that drilled in my head, I wouldn’t have had anything to come back to,” Deena said. “Or I probably wouldn’t have even felt ashamed for, like, the things that I was doing. Because it’s so typical and it’s so normal. But to have seen different at KIPP, it opens your eyes.”

Like Deena, Zuleika has remained close to home. She lives with her mom and her new husband in North Philadelphia.

Both women work in child care. Neither of them have become wealthy or left the hard-scrabble neighborhoods where they grew up.

But they also both have post-secondary degrees, something their parents didn’t have at this age. And they both seem to be happy, stable.

‘What we measure’

Anecdotal evidence aside, what can we really say about the effectiveness of KIPP? And what about the school’s ambitious promise to get every student to and through college?

Here’s what the numbers say.

Six years after high school graduation, 35 percent of the original KIPP Philly class had an associate’s or bachelor’s degree. At the seven-year mark, that number was 44 percent.

What does that mean?

In Philadelphia, about a quarter of students who graduate high school earn a college degree by the six-year mark. That overall Philly number would be lower if you tracked students back to eighth grade, like KIPP does.

There’s a prominent nationwide study that tracked students starting in 10th grade.

It found that eight years after high school graduation, about 14 percent of students from the lowest income quartile had a degree.

KIPP Philly students almost all came from poor neighborhoods, and the results suggest that they earned degrees at much higher rates — rates that are about the same as middle-income students.

“And that feels like we did something that was real,” said Mannella, the school’s founder.

There are serious caveats, though.

KIPP’s number doesn’t count all the kids who left over those four years. Some of those kids did graduate college. Some didn’t. It’s quite possible that the 34 who made it through KIPP were more likely to have long-term academic success for a whole host of reasons, no matter what school they attended.

Frankly this project is incomplete, too.

We talked with 24 of the 34 alum from the original class — as well as nine students who attended KIPP Philadelphia but didn’t finish. The ten graduates who chose not to talk may have very different experiences than the 24 who did.

Still, the biggest caveat of all is that there’s really no baseline to compare. Other schools — especially middle schools — don’t keep that data.

Even the data that Philadelphia does have on its high school graduates isn’t front-page material. To find it, you have to navigate to a backwater part of the school district’s website.

Mannella thinks the lack of data is, itself, a problem.

“What we measure, we work on. And so right now we work really hard on eighth grade test scores,” he said, referring to Pennsylvania’s standardized testing schedule. “I think that there is an opportunity to change the dialogue and to really change our schools for the better if we would actually start to measure something else.”

When you look back on the early days of KIPP Philadelphia, it’s easy to focus on the stuff that looks super different. The yellow PIP shirts. The long school day.

But part of what makes the school experimental is the length of the experiment.

Most schools don’t judge themselves based on what happens 10 or 20 years down the road.

“And that gets you short sighted decisions that are focused on, I would argue, the wrong outcomes,” Mannella said.

He thinks that if more schools looked at long-term goals, you’d have more teachers like Susan Larson. He thinks schools would have to work harder. He thinks schools would have to think more about their purpose, their big-picture purpose.

“Anything less feels incremental,” he said. “Anything less feels unworthy.”

This sounds nice in theory. It also seems impractical.

How would this type of accountability work? Would you actually judge 7th-grade teachers based on how their students turned out 10 or 20 years later? Would that even work given how many teachers students have in a lifetime?

It’s difficult to make much of KIPP’s numbers since the school has changed significantly since its inception. In general, enthusiasm for “no excuses” charters seems to be fading.

Even if we accept the fact that KIPP did something right, do we know whether that “something” is still there?

There is a small generation of research emerging from the earliest batch of “no excuses” charter schools — research that tracks the kind of long-term outcomes that these schools made central to their missions. There are signs that the schools boosted college attendance and students’ proclivity to attend well-regarded colleges. The data on college completion is less conclusive.

In conversations with researchers who’ve done these studies, many of them acknowledged there’s a lot we still don’t know. They’re curious about how these students will fare in the working world. Will they earn more? Will their children benefit?

The answers to these questions aren’t as obvious as you might think.

The effectiveness of an educational intervention can wax and wane with time. One well-known study showed that classroom size and teacher effectiveness can matter a lot in the short-term. The gap narrowed to almost nothing when students got older. But then, like magic, it reappeared on some measures when researchers followed the students into the “real” world.

All that makes you wonder whether college completion is even the right metric to use if you want to measure a school’s long-term effectiveness.

After all, a degree isn’t really a life outcome. It’s just another indicator.

“I understand that there’s a reductivism to only focusing on college graduation,” said Mannella. “But if you’re talking about the best proxy we have in America for setting someone up to live the rest of their life, that’s still it.”

Susan Larson thinks KIPP’s early results in Philly are promising. They seem to suggest the school did something. She also doesn’t care about those numbers.

“I’m not a data person, so that wasn’t the end-all-be-all because in those numbers are students names — and then that’s where I lie,” she said.

Those names include:

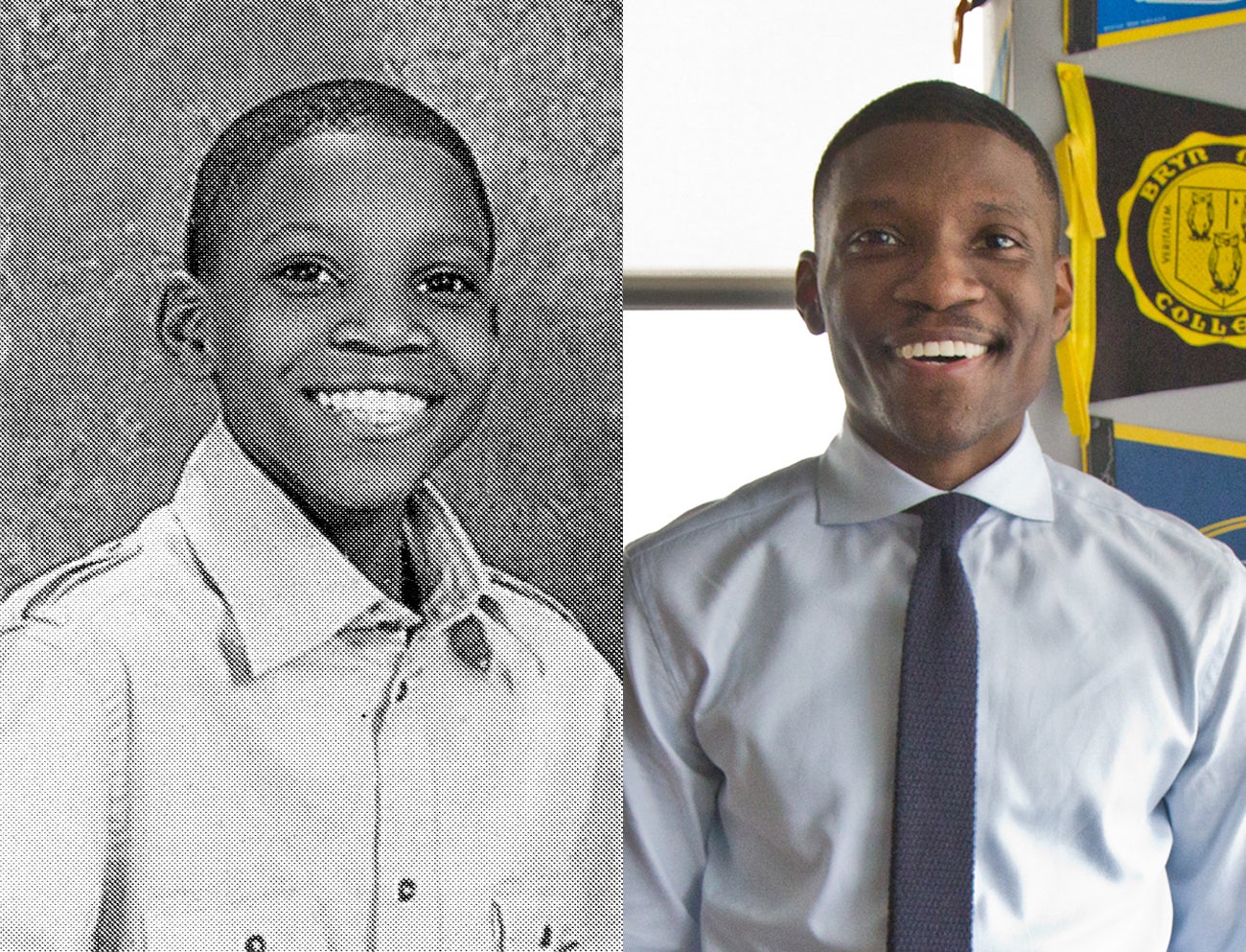

Christopher Johnson, chief of staff to a Democratic state representative from Philadelphia.

Britanny Carroll, mother of three trying to work her way through college.

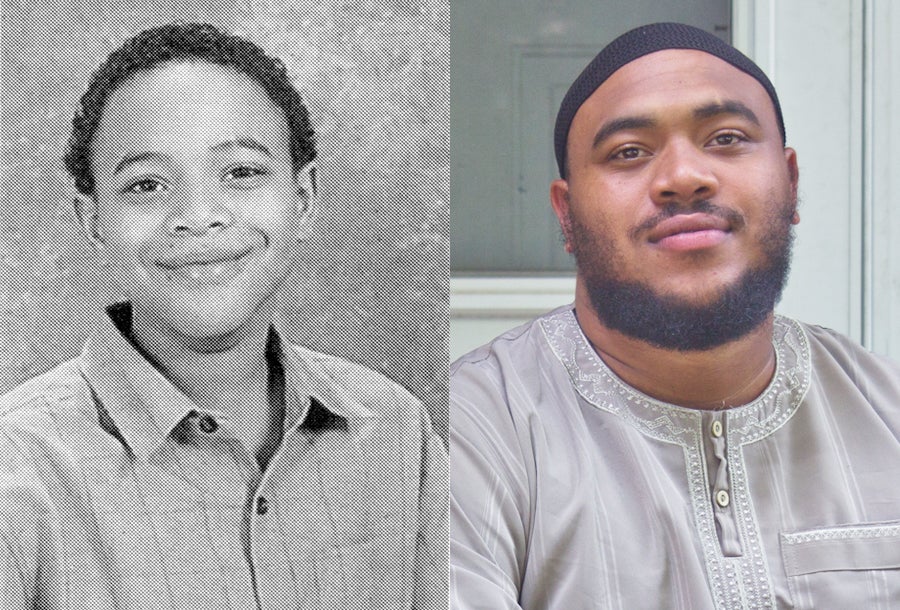

Shakoor Sanders, jazz percussionist.

Markesha Burnett, budding social media marketer.

Courtney Scott, graduate of one elite college and employee at another.

Lakshmi Miranda, postal worker.

As those students grew, so did Susan’s perspective.

In the beginning she lived by the “college, college, college” orthodoxy KIPP laid out. She doesn’t anymore.

“When they went off to school and some of them started coming back…that’s sort of when the KIPP through college tone changed,” she said.

We came into this story trying to understand whether KIPP made a difference in the lives of its students.

But what are we even aiming for? What’s the goal?

KIPP said the goal was college. But the woman responsible for getting students to that goal realized that approach could be too narrow.

Maybe they needed to think bigger.

“We need you to be financially independent and happy and then that’s all that matters,” Larson said. “Like if you don’t finish your degree, that’s fine. Let’s just figure out something that you like to do so when you get up in the morning you don’t dread going to work.”

How would you try to measure or capture this? Household income? A happiness meter?

It’s a tough code to crack.

But if you at least contemplate these questions, it leads you to stories like Jayuana Bullard’s.

Because of all the students who said KIPP changed them, no one said it with as much force and feeling as Jayuana.

‘The marshmallow’

Jayuana grew up in the Strawberry Mansion section of North Philadelphia, raised by her mom and grandmother.

She came to KIPP in 6th grade from Catholic school. The KIPP discipline system appealed to Jayuana’s mom. Jayuana wasn’t a huge fan. But she liked the intensity and intimacy of the environment.

“Everyone was just so excited,” she recalled. “It felt like they were proud of you…like you were their own kid.”

Jayauana doesn’t have an academic miracle story to tell. You can tell from talking to her and reading her writing that she’s smart. She says she was always a good student.

She spent three consecutive years at KIPP, graduating with the first class in 2007. It was a rare run of stability in a tumultuous life.

After middle school, she started arguing with her mom, a lot, and decided to live with her dad across town.

He committed suicide midway through her sophomore year. And there are two versions of what happened next.

Jayauna’s mom says her daughter needed psychiatric help. Jayauana says her mom didn’t want to deal with her and had her committed.

“I just thought that she hated me all of a sudden,” Jayuana said.

Jayuana went to a psychiatric hospital and then a series of schools for kids with behavioral problems.

At one point Jayuana says she lived in a crack house for about month before police found her and returned her to her mother’s custody — which led to another stint at an alternative school. Somewhere along this bumpy road her college dreams faded.

“It wasn’t like, ‘OK, I don’t want to go to college anymore,’” Jayuana said. “It was more so, ‘Where am I going to live next month?’”

After finishing high school, Jayuna moved in with a friend who suggested she try stripping for money. She had no cash and no prospects. At 17, she fudged her age and started working at a West Philadelphia club.

She still had regular contact with KIPP teachers and recalls, with fondness, their attempts to guide her. Susan Larson once brought her a microwave for an apartment she’d rented. Another teacher hooked her up with a restaurant job when Jayuana attempted to quit stripping.

Dancing called her back, though. She’d grown to like it.

“You feel like you’re in charge,” she said. “I felt this kind of sense of being in control that I had never really felt before.”

Whenever Jayuana got tired of Philly she’d travel with a colleague to Houston or Atlanta or New York. She’d grab a hotel room, audition at a few clubs, and spend a couple weeks exploring some new part of the country.

“Coming from no freedom at all, it was very important to me that I had that,” she said. “Like, I loved it. I loved it a lot.“

Jayuana lived fast. A little too fast.

She was arrested on drug charges in 2016. She says the drugs belonged to her ex-boyfriend, a dealer.

She got probation and the ordeal convinced her to slow down. She stopped dancing a year-and-a-half ago. She has a new boyfriend and they live on a quiet suburban cul-de-sac.

Our interview took place in the spare room she keeps at a house her grandma once owned in Strawberry Mansion. She wants to fix the place up and flip it.

Jayuana likes the idea of going into business — either real estate or a food cart. She doesn’t plan to go back to school.

She knows she did not follow the path KIPP laid out. It bothers her, especially when she thinks about her old teachers.

“I wonder if they felt like they failed somehow or anything like that,” she said. “But they didn’t.”

Jayuana is not a college graduate. She may never be.

But she looks at the outcome through a totally different lens. It’s not what she is. It’s what she isn’t.

“I think with all of the hard situations that I’ve had to deal with, I could be like a crack whore right now,” she said. “I could be…I could be dead. Like, there’s been times where I’ve got so depressed where I thought about giving up.”

But then she hears a voice in her head.

“You don’t give up,” it says. “You find a way.”

Jayuana says that mantra came from KIPP.

“If this way is not working for you — you have a goal and you need to get it — you find a fucking way,” Jayuana said. “Figure it out, because anybody who ever got something done pushed themselves and figured it out and found a fucking way.”

KIPP has a four-word slogan.

Work hard. Be nice.

Jayuana would say it to herself when she got to a new city to look for dancing gigs. She still repeats it to herself.

So how did it stick? Why did these ideas sink so deep into her brain?

Jayuana says it was some combination of repetition and affection. A group of people that cared about her preached the same message so consistently she adopted it as her own.

“They tell you this every single day,” she said. “No way it can’t stick — especially if you’re going through hard things and you need something to push you to keep you going. They gave that to me.”

A bunch of the alum told me about these shirts KIPP used to print up that said, “Don’t Eat the Marshmallow.”

It’s a reference to a social science experiment where researchers found that little kids who showed self-control had better life outcomes than those who didn’t.

It’s almost too on the nose — a school that was itself a kind of laboratory tried to shape kids by teaching them about another social experiment.

But Jayuana bought in.

“They are not just slogans,” she said. “They’re not just things they paint on the wall. These are real ways to live your life, real ways to live by. As long as you have some self-discipline, as long as you don’t eat the marshmallow, everything’s going to be cool. And that is a big part of my life right now. It’s always been.”

Work hard. Be nice.

Those words are supposed to get you through college — not through a night-club audition.

And if you go by the numbers, KIPP did not work for Jayuana.

That’s fine. Numbers will never account for everything.

But it does seem like we should somehow try to capture stories like Jayuana’s when we talk about school success.

A school can help you years after you leave its doors. It can change your life.

Jayuana Bullard says she’s living proof.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.