Why should we pay ex-presidents?

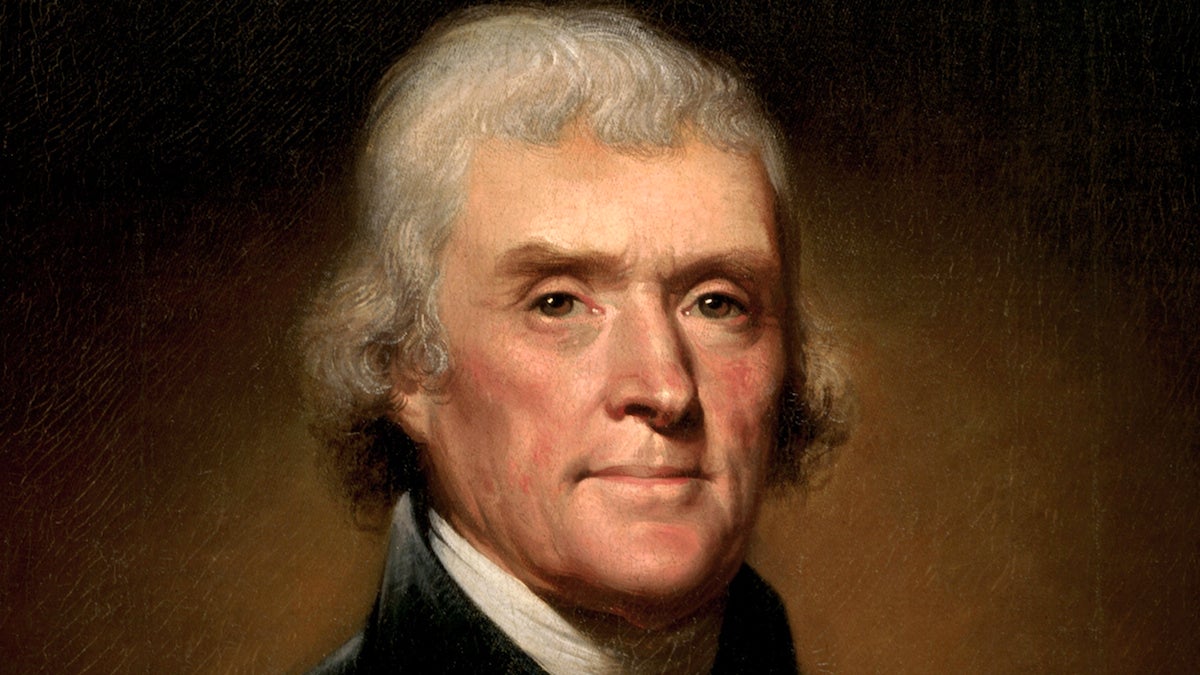

After leaving the White House Thomas Jefferson had to sell his 6,000-volume book collection to the government—forming the core of the Library of Congress—to pay off his creditors;

What will Barack Obama do after he’s done being president? Make money, that’s what.

No matter how he spends his time–law professor? foundation executive?–Obama will take in a $200,000 annual pension from you, the taxpayer. It’s pegged to the salary of a Cabinet secretary, and it will rise when that salary does.

But Obama’s net worth right now might be as high as $7 million, according to his 2015 disclosure forms. And he’s already under contract with Crown Publishing to write a book after he leaves the White House, which will bring in millions more.

Does anyone see a problem with this picture? Obama’s pension dates to a time when ex-presidents often needed the money. But now they don’t. So it’s time to retire the pension for retired Presidents.

Ironically, the poorest former presidents never got a pension at all. In the 19th century, Thomas Jefferson was forced to sell his 6,000-volume book collection to the government—forming the core of the Library of Congress—to pay off his creditors; his debt-ridden successor, James Madison, pleaded in vain for a loan from the new Bank of the United States; and the next president, James Monroe, was so impoverished upon is death in New York that his family could not afford to send his remains back to his native Virginia.

So far as we know, however, none of these ex-presidents pleaded for a pension. In these early years, with the Revolution against King George still a fresh memory, a lifetime government sinecure smacked too much of royal privilege.

The first ex-president to demand a pension was also one of the least distinguished: Millard Fillmore. “It is a national disgrace that our Presidents should be cast adrift, and perhaps be compelled to keep a corner grocery for subsistence,” wrote Fillmore, whose savings were nearly wiped out by the Panic of 1857.

A quarter-century later, when his own nest egg disappeared in a stock fraud, Ulysses S. Grant would pioneer a new form of ex-presidential profit-making: the memoir. Published by Mark Twain, who was also suspected as its ghost-writer, Grant’s two-volume memoir was completed just before he died of throat cancer. But it did earn nearly a half-million dollars in royalties for his cash-strapped family and untold other profits for Twain’s book company, which employed former Union soldiers in full uniform as salesmen.

By the end of the 19th-century, ex-presidents moved into another lucrative area: serving on corporate boards. Grover Cleveland sat on two of them, both in the graft-ridden insurance industry, which earned him lots of bad press along with big fees. Cleveland apparently felt bad about it, too, urging Congress to establish a pension that would obviate the need for such money-grubbing.

But the pleas fell on deaf ears, even after steel magnate Andrew Carnegie offered to underwrite a $25,000 annual pension for the president in 1912. Hoping to shame Congress into establishing an official pension, Carnegie’s gambit probably delayed it still further. “I am not sure that an ex-President who would accept such a pension would receive or be entitled to the continued respect of the people of the United States ,” declared Thomas Gore, senator from Oklahoma (and author Gore Vidal’s grandfather).

Four decades later, the plight of Harry Truman gave birth to the modern presidential pension. A failed haberdasher and a poor investor, Truman was so broke upon leaving the White House that he had to move in with his mother-in-law in Missouri . He also bought his train ticket out of Washington by himself, which the public saw as beneath the dignity of an ex-president.

So in 1958, Congress passed the Former Presidents Act. It gave ex-presidents a lifetime pension—equal to the annual salary of a Cabinet secretary—as well as compensation for travel, staff, and other expenses.

But these were also the years that ex-presidents realized huge new financial opportunities. Truman himself got a $670,000 advance for his memoirs. He also received a large fee for appearing on Edward R. Murrow’s television program See it Now, becoming the first ex-president to cash in on this new medium.

After that, ex-presidents reaped the harvest. Memoirs were always a safe bet, earning anywhere from $2.5 million (Richard Nixon) to Bill Clinton (a reported $15 million). So were corporate boards and advising, which Gerald Ford (American Express, 20th Century Fox) and George H.W. Bush (the Carlyle Group) exploited to the fullest.

And then there were speaker fees. Nine months after leaving the White House, Ronald Reagan got $2 million for a few talks to a communications firm in Japan . But nobody came close to Bill Clinton, who took in over $50 million from speaker fees alone between 2001 and 2007.

So here’s the paradox. When presidents really needed a government pension, then didn’t get one; and now that they don’t need one, we give it to them.

Already awash in riches, President Obama should renounce his pension. And Congress should do away with it, once and for all, lest we bestow still more wealth on future presidents. As more and more Americans struggle to pay their bills, this is one cost that we shouldn’t have to pay.

Jonathan Zimmerman teaches history and education at New York University. He is the author of Too Hot to Handle: A Global History of Sex Education, which was published in March by Princeton University Press.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.