When celebrities go on trial, we can’t help but watch

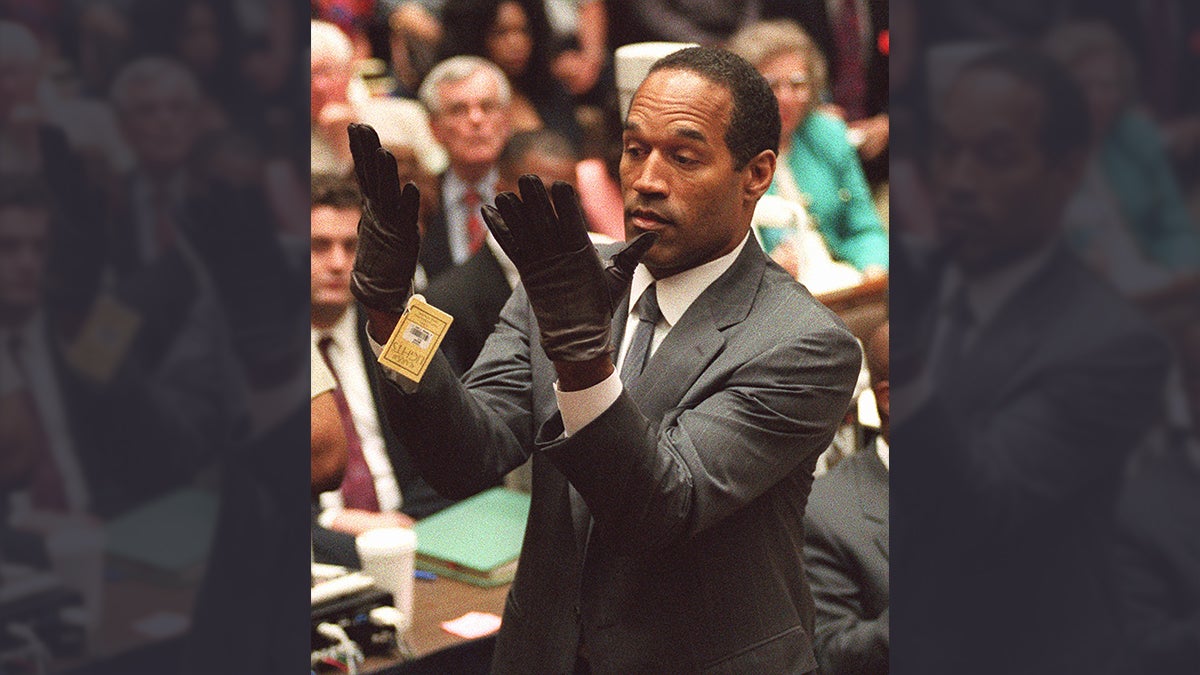

O.J. Simpson holds up his hands before the jury after putting on a new pair of gloves similar to the infamous "bloody gloves" during his double-murder trial in Los Angeles, in this June 21, 1995 file photo. (AP Photo/Vince Bucci, Pool)

In the midst of Bill Cosby’s sexual assault trial, fans across generations are in a state of disbelief. Since dozens of women have come forward with accusations of sexual assault, Cosby’s character has come into question.

Celebrity trials have created cultural frenzies and left their marks on society for decades. While the nature and severity of the crimes in question may be starkly different from each other, here are some highly publicized celebrity criminal trials that have exposed previously hidden aspects of celebrities’ identities.

Fatty Arbuckle

Comedian Fatty Arbuckle is pictured at an unknown location, Nov. 24, 1920. (AP Photo)

Comedian Fatty Arbuckle is pictured at an unknown location, Nov. 24, 1920. (AP Photo)

In September 1921, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, the original star of the Keystone Kops silent films, was charged with the rape and manslaughter of actress Virginia Rappe.

Arbuckle had a successful career writing screenplays, directing, and acting. He was known for being one of the first Hollywood actors to demand a million-dollar contract and creative control over his films.

Rappe had become ill at a party that Arbuckle hosted at the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco, and she was hospitalized two days later. She suffered from a chronic condition called cystitis, which was exacerbated by her drinking habits and several abortions. Four days after the incident, Rappe died in the hospital of peritonitis, abdominal bleeding.

Rappe’s friend accused Arbuckle, who was 266 pounds, of unintentionally crushing her during non-consensual sex. A rumor began circulating that Arbuckle had raped her with a sheath of ice — causing the internal injuries — which escalated to claims that it was a Coke or champagne bottle. Arbuckle staunchly denied all of these claims, and a doctor said there was no evidence of rape.

He stood trial three times. The first two trials ended in hung juries, while the third acquitted Arbuckle after deliberating for only six minutes. They even wrote Arbuckle a formal apology for the injustice he had suffered.

Arbuckle’s career was absolutely destroyed after the trial, largely because his case had been sensationalized and exaggerated by journalists. His films were banned for a year afterward. He started working under the alias William Goodrich, which allowed for slight success, until he died of a heart attack at age 46.

Charles Manson

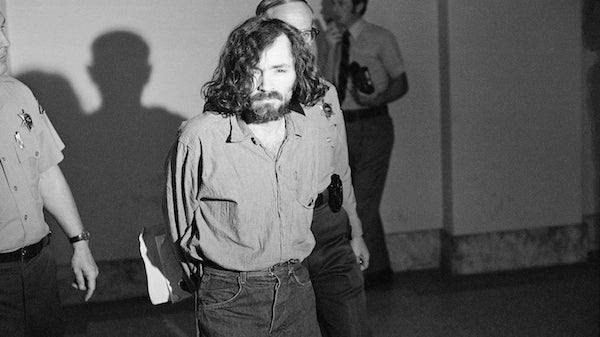

Charles M. Manson, squinting in the glare of a film cameraman’s floodlight, marches to court, Aug. 20, 1970, for a hearing on his claim he is being mistreated by deputies in the Los Angeles County Jail. (AP Photo/George Brich)

Charles M. Manson, squinting in the glare of a film cameraman’s floodlight, marches to court, Aug. 20, 1970, for a hearing on his claim he is being mistreated by deputies in the Los Angeles County Jail. (AP Photo/George Brich)

After his release from prison in the late 1960s, Charles Manson cultivated a cult-like following in San Francisco. The “Manson Family” honored Charles like a guru and traveled around in a converted school bus. The cult sought to kill dozens of elite, white celebrities, hoping that these murders would spark a black rebellion against the white establishment. Manson called the coming race war “Helter Skelter,” believing it had been prophesied in the hit Beatles song of the same name, and planned to survive the war by living underground in Death Valley and eventually becoming allies with the “blackies.”

It is believed that Manson’s motive for these killings was rooted in his personal resentment toward elite celebrities who continually prevented him from gaining success as an actor.

In August 1969, Manson and six cult members were accused of committing seven murders: actress Sharon Tate and several of her acquaintances, Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, Bernard Crowe, and Gary Hiname. The defendants showed no remorse for their crimes throughout the seven-month trial, and in January of 1971, Manson and five of his cult members were convicted on seven counts of first-degree murder. All were sentenced to death but now serve life sentences after the death penalty was abolished in California in 1972. While several have been released or have passed away, Manson continues to serve out his life sentence.

“Mr. and Mrs. America,” stated Manson after his conviction, “you are wrong. I am not the King of the Jews nor am I a hippie cult leader. I am what you have made me and the mad dog devil killer fiend leper is a reflection of your society … Whatever the outcome of this madness that you call a fair trial or Christian justice, you can know this: In my mind’s eye my thoughts light fires in your cities.”

Several books have been written about the Manson murders, including “Helter Skelter” by Curt Gentry and Vincent Bugliosi, who served as the prosecutor in the trial.

Roman Polanski

Film director Roman Polanski arrives at court in Santa Monica, Ca., Aug. 8, 1977. Polanski is to enter a plea on charges that he drugged and raped a 13-year-old girl. (AP Photo)

Film director Roman Polanski arrives at court in Santa Monica, Ca., Aug. 8, 1977. Polanski is to enter a plea on charges that he drugged and raped a 13-year-old girl. (AP Photo)

The director of “Rosemary’s Baby” and “Chinatown” was arrested in Los Angeles in March 1977, and charged with five offenses against 13-year-old Samantha Gailey: rape by use of drugs, furnishing a controlled substance to a minor perversion, sodomy, and lewd/lascivious acts upon a child under 14.

Polanski’s pregnant wife, Susan Tate, had been murdered by Charles Manson and his cult in 1969.

Polanski pleaded not guilty to all charges. However, he later accepted a plea bargain that dismissed the five initial charges in exchange for pleading guilty to the charge of engaging in unlawful sexual intercourse. In February 1978, mere hours before he would have been formally sentenced to deportation and imprisonment, Polanski fled to France, where he still lives. He has continued his successful Hollywood career from abroad, avoiding travel to any countries likely to extradite him to the United States. He won an Oscar for his film “The Pianist” in 2003.

Woody Allen

Woody Allen, left, and his attorney Elkan Abramowitz, right, enter a news conference in New York Friday, Sept. 24, 1993. At the news conference Allen lashed back at the prosecutor who said, he believes Allen molested his adopted daughter but decided against charging the filmmaker in order to avoid a traumatic trial for the young girl. Woman is unidentified. (AP Photo/Joe Tabacca)

Woody Allen, left, and his attorney Elkan Abramowitz, right, enter a news conference in New York Friday, Sept. 24, 1993. At the news conference Allen lashed back at the prosecutor who said, he believes Allen molested his adopted daughter but decided against charging the filmmaker in order to avoid a traumatic trial for the young girl. Woman is unidentified. (AP Photo/Joe Tabacca)

In 1992, 7-year-old Dylan Farrow — adopted daughter of Mia Farrow and Woody Allen — told her mother that Allen had touched her inappropriately, promising to take her to Paris and let her star in a movie. Earlier that year, Farrow had found nude photos of her other adopted daughter from her previous marriage, Soon-Yi Previn, about 20 years old at the time, in Allen’s home. A custody fight ensued.

After a doctor had interviewed Dylan several times, he claimed that her statements seemed to be rehearsed, perhaps because her mother had told her what to say, or as a result of trauma related to the incident. In court, Allen’s relationship with Previn — whom he went on to marry in 1997 — was used against him. The judge also upheld that the evidence given by the doctor could have been tainted by his loyalty to Allen.

Custody of the couple’s children, Dylan, Moshe, and Ronan, was awarded to Farrow. The judge maintained the position that there might still be sufficient evidence to prove sexual abuse against Dylan. In 1993, Connecticut state’s attorney Frank S. Maco announced that he was dropping Dylan’s case, as she was too “fragile” to continue with the trial. Dylan has since spoken out against her adoptive father and about her alleged assault.

O.J. Simpson

O.J. Simpson and his defense attorney, F. Lee Bailey, left, consult with each other, Friday, June 30, 1995, during the Simpson double-murder trial in Los Angeles. At right is Simpson defense attorney Carl Douglas. (AP Photo/Reed Saxon, Pool)

O.J. Simpson and his defense attorney, F. Lee Bailey, left, consult with each other, Friday, June 30, 1995, during the Simpson double-murder trial in Los Angeles. At right is Simpson defense attorney Carl Douglas. (AP Photo/Reed Saxon, Pool)

In his infamous trial, the former NFL player and actor was charged with the murder of his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend Ron Goldman in June 1994. The case lasted 11 months, from November 1994 to October 1995. Simpson was represented by a number of high-profile defense attorneys known as the “Dream Team” — led by Robert Shapiro (who was succeeded by Johnnie Cochran), and including Robert Kardashian and two attorneys specializing in DNA evidence.

DNA evidence was a relatively recent development in criminal cases. The specialists were able to convince members of the jury that there was “reasonable doubt” about the DNA evidence presented by the prosecution. There was also considerable debate over the bias of the jury, use of evidence (especially forensics), and the influence that Simpson’s race and fame might have had on the outcome of trial.

On the morning of Oct. 3, 1995, it is estimated that 100 million people tuned in to hear the verdict. A hundred officers on horseback were ordered to surround the courthouse in the event of riots, and President Bill Clinton was briefed on the security measures to be enacted if rioting were to extend to other areas of the country. An estimated $480 million was lost in workplaces around the country due to decreased productivity at the time of the verdict.

In 1997, after Simpson was acquitted, the victims’ parents filed a civil suit against him. The trial took place over the course of four months in Santa Monica, California. Simpson was found “responsible,” and he was ordered to pay $33.5 million to the families of the victims.

Simpson’s case is considered the most publicized criminal trial in history and was deemed the “trial of the century.” After extensive controversy, the judge ruled that television coverage of the trial was warranted, which allowed for a lot of public attention. The trial — especially the initial low-speed car chase following the murders — was a highly emotional, minute-by-minute collective experience among viewers, who often expressed feelings of personal investment and interest as Americans. The “Big Three” television networks broadcast near-constant coverage of the trial, and the L.A. Times maintained the case as a front-page story for over 300 days after the murders. Several books have been written about the case, including one by Simpson himself, and another proposed only two hours after the bodies were found.

As with Cosby, contentious racial issues were also a key element that brought the Simpson trial public attention and media coverage. Even after the trial ended, surveys depicted a major divide in public opinion about the outcome of the case based on race.

Simpson is currently serving out a 33-year sentence after being convicted of multiple felonies in 2007. He will become eligible for parole in October.

Phil Spector

This May 23, 2005 file photo shows music producer Phil Spector during his trial at the Los Angeles Superior Court in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes, File)

This May 23, 2005 file photo shows music producer Phil Spector during his trial at the Los Angeles Superior Court in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes, File)

The iconic record producer was charged with the murder of actor Lana Carson in September 2003. He was 69 years old. Spector had met Carson at the House of Blues on L.A.’s Sunset Strip during a night out, and she agreed to go back to Spector’s mansion for a nightcap. Carson was found later that night in his home with a bullet through the roof of her mouth. Spector was charged with her murder, although he claimed that Carson had committed suicide at his home.

Spector’s case is interesting in that it continued for so long, despite the existence of considerable evidence against him — likely because he was able to spend a lot of money on his defense. “I think I killed someone” were Spector’s famous words, uttered under his breath as he emerging from his house on Feb. 3, 2003, following the incident.

The trial is often remembered by Spector’s elaborate performances throughout; wearing outlandish wigs and eccentric outfits to court, trophy wife on his arm, and accompanied by several bodyguards. It became one of the most-watched trials in history. The first of his two trials ended in a mistrial when jurors were unable to reach a verdict. In the second trial in 2009, he was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to 19 years to life in prison. Spector will not be eligible for parole until 2028.

Michael Jackson

Michael Jackson flashes the V sign at cheering fans as he arrives for his child molestation trial at the courthouse in Santa Maria, Calif., Friday. May 13, 2005. (AP Photo/Reed Saxon)

Michael Jackson flashes the V sign at cheering fans as he arrives for his child molestation trial at the courthouse in Santa Maria, Calif., Friday. May 13, 2005. (AP Photo/Reed Saxon)

Between January 2004 and June 2005, the “King of Pop” stood on trial for a 2003 charge of child molestation against Gavin Arvizo, among 14 total charges. Jackson had financially supported the Arvizo family — the prosecution — for several years after 10-year-old Gavin was diagnosed with cancer. Jackson befriended the boy, who had visited Neverland Ranch, Jackson’s home, several times. Gavin claimed that Jackson had gotten him drunk, when he was 13 years old, and molested him.

The prosecution argued that Jackson had lured Gavin with his mystical estate, lowering his inhibitions and making the assault possible. The family was portrayed by the defense as having a pattern of taking advantage of celebrities and legal and governmental resources for their own financial gain.

The trial is often remembered for the public excitement it incited. Jackson once climbed atop an SUV and danced for the fans waiting for him outside the courthouse. He showed up to trial one day wearing pajamas. Upon his acquittal, fans waiting outside the courthouse threw confetti. One released one dove for every charge on which Jackson was acquitted. Crowds gathered to celebrate in New York’s Times Square under a screen announcing his acquittal.

However, the trial itself was much more private. No cameras were allowed in the courtroom, and a gag order was placed on all participants in the trial. Jackson’s career was already declining at that point, as was his health, and he died from a drug overdose in 2009.

Dr. Conrad Murray

Michael Jackson fans gather outside the Los Angeles Criminal Court on Monday, April 5, 2010, where Dr. Conrad Murray, the doctor charged in Michael Jackson’s death, appears for a procedural hearing in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Nick Ut)

Michael Jackson fans gather outside the Los Angeles Criminal Court on Monday, April 5, 2010, where Dr. Conrad Murray, the doctor charged in Michael Jackson’s death, appears for a procedural hearing in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Nick Ut)

Dr. Conrad Murray, Jackson’s personal physician, was charged with involuntary manslaughter after the singer’s death in June of 2009 from an extreme overdose propofol, a general anaesthetic. Throughout the televised trial, Murray’s defense claimed that Jackson, exhausted from the strain and pressure of rehearsing, had taken eight tablets of Ativan before self-administering the massive dose of propofol. The mixture of these medications killed Jackson almost instantly.

Murray normally stayed with Jackson about six nights a week, who often begged him for drugs that would put him to sleep. On Nov. 7, 2011, Murray was found guilty of involuntary manslaughter and was sentenced to four years in prison, although he was released after two for good behavior and as a result of overcrowding in the prison.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.