Vision Zero: What it is, and why Philly Mayoral candidates will be talking about it

Sometimes the most powerful political innovations are born not because someone invents a brand new issue, but because someone invents a new story to tell about why some existing ideas fit together in a new way that makes them politically compelling.

Usually this process involves turning a problem that everyone believes is completely accidental and no one’s fault into an issue that has a purpose and a cause – and often a villain.

This is the crux of the political innovation behind Vision Zero – the hottest political issue you didn’t know you cared about yet, which is headed straight for this year’s 2015 Mayor and Council campaigns.

As Ashley Hahn mentioned, the idea made its way into the Bicycle Coalition’s Better Mobility 2015 platform, and BCGP is receiving a $10,000 grant Wednesday from Advocacy Advance (a partnership between the League of American Bicyclists and the Alliance for Biking and Walking) to support advocacy efforts around it.

So what is Vision Zero?

The short answer is that it’s a promise extracted from candidates for office to take responsibility for achieving zero bike or pedestrian traffic fatalities over a given time period.

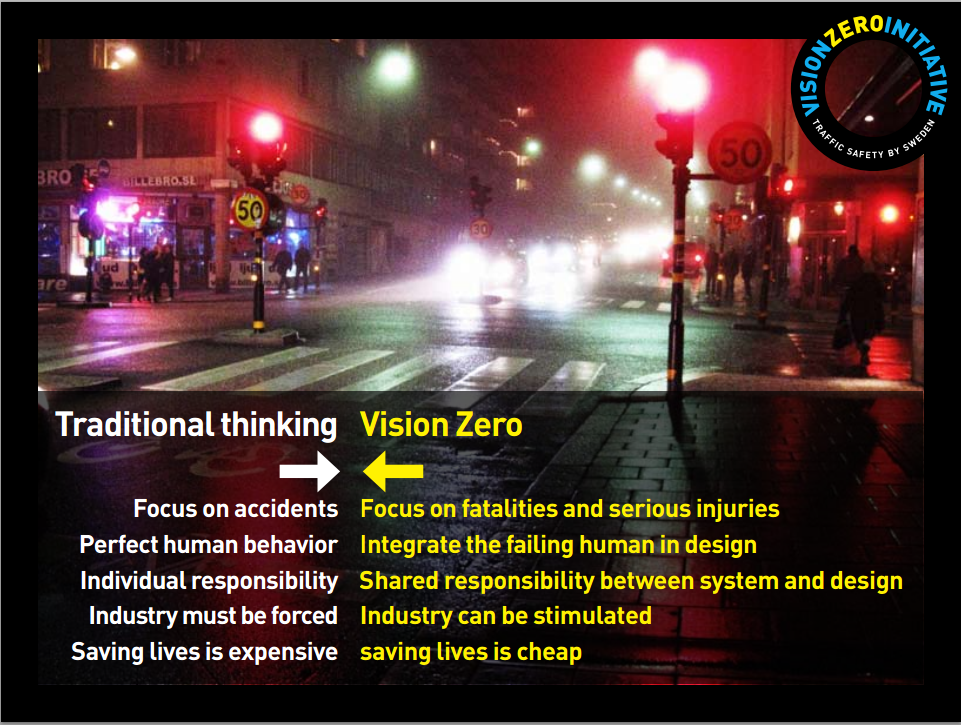

Invented in Sweden in 1997, the premise is that there’s no such thing as an accident, and “life and health can never be exchanged for other benefits within the society.” It’s a pretty radical and categorical rejection of the idea that fast travel speeds for cars on city streets can sometimes be allowed to impinge on safety goals.

The longer answer is that promising zero fatalities sets a politician up for certain failure, at least in the medium term, so the cities that have adopted this approach have set more achievable (but still aggressive) benchmarks for bringing down the death toll through changes to street design and engineering, stepped up law enforcement, and education for all street users. Equally important are efforts to change the culture within the various city agencies with relationships to streets policy.

The two US cities who have adopted the policy so far – New York City and San Francisco – have set different medium-term goals. New York City Mayor Bill DeBlasio has committed to reducing traffic deaths by half by 2030, and San Francisco wants to achieve the same goal by 2024.

Rather than create a new city agency or make dramatic changes to the structure of city government, DeBlasio established a Vision Zero Task Force tasked with coordinating changes to policies and procedures within a broad array of agencies including the NYPD, the Taxi and Limousine Commission, the Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities, the Department of Education, NYC Health, and the Department of Aging.

We’ll be reporting on their progress from a symposium hosted by NYC DOT this Friday, but the program appears to work where it is tried. Their Vision Zero action plan surveys the record:

In Sweden, the most famous example and originator of Vision Zero, traffic fatalities have dropped 30% since 1997. In Minnesota, Utah and Washington State, traffic fatalities have fallen steadily since the introduction of Vision Zero-style programs in the early 2000’s; a 43% reduction in Minnesota, 48% reduction in Utah and a 40% decrease in Washington. While traffic fatalities nationwide are falling, largely due to improvements in emergency/trauma care and vehicle enhancements such as airbags, fatality rates in Vision Zero states fell over 25% faster than the nation since 1997.

To put that in context, between 2008 and 2012, Philadelphia witnessed 8,690 collisions involving 9,051 pedestrians. Those collisions caused 376 major injuries and 158 deaths. Here is a map of the hot spots identified by Azavea’s Daniel McGlone:

Cutting those numbers in half will be a challenge, but whether the challenge is achieved in time is less important than, as the NYC DOT’s Vision Zero action plan puts it, a change in politicians’ and city officials’ mindset that “accepts no traffic fatality as inevitable.”

Changing the political values, and particularly the conception of these tragedies as blameless accidents, is the hardest part. But once the commitment is established, it makes the policy changes much easier to move.

Taken separately, any one of the policies Vision Zero could entail (narrower travel lanes to reduce car speeds, pinched intersections and raised crosswalks, more separated bike infrastructure, lower speed limits, and automated speed enforcement, to name a few) would be unlikely to pass City Council or the state legislature today. But working backward from an established commitment to zero fatalities or serious injuries, the total package becomes more difficult for politicians to turn down.

Is this going to work in Philly?

At a listening session for the Bicycle Coalition’s 2015 platform earlier this week, BCGP director Alex Doty said that all of Philadelphia’s advances in bicycle infrastructure over the years are the result of promises secured by cycling advocates from candidates during political campaign season.

Indeed, the situation has played out in similar fashion in New York City, where advocacy groups like Transportation Alternatives, Streetsblog New York City, StreetsPAC, and Families for Safe Streets largely foisted the street safety issue upon reluctant politicians, rather than politicians coming around to these positions of their own volition.

At the outset, the 2013 NYC Democratic primaries had the feel of a backlash election against Michael Bloomberg and his DOT head Janette Sadik-Khan’s aggressive traffic calming policies. Bloomberg’s potential successors were champing at the bit to run against an elitist “War on Cars,” as the New York Post had framed it. Ex-Congressman Anthony Weiner expected to ride the bikelash into office, memorably telling Bloomberg in 2011 he would “have a bunch of ribbon-cuttings tearing out your f……g bike lanes” and calling livable streets advocates “policy jihadists.”

But by the summer of 2013, a funny thing happened – months of focused advocacy by livable streets proponents, and the introduction of the Vision Zero issue had successfully reframed the debate over bike lanes and pedestrian infrastructure as an issue of safety for vulnerable populations, rather than promoting access to alternative transportation. Candidates for Mayor and City Council sensed a political opportunity to distinguish themselves by competing to be the most concerned about street safety. Even Congressman Weiner began posting pictures of himself riding a Citi bike to his Facebook page.

The idea of safety equity also played a role in changing the politics. In New York City, as in Philadelphia, pedestrian collisions are more likely to occur in economically distressed areas – a political fact that has helped to move the debate in NYC away from unwinnable terrain (middle class car commuters vs. white hipster cyclists) into a more winnable frame (grieving families and endangered schoolchildren vs. negligent drivers and out-of-touch traffic engineers.)

The result has been that the same, or even greater levels of traffic calming are happening in NYC, but where those interventions are primarily happening has changed. The best-known projects of the Sadik-Khan era at NYC DOT were in Times Square, Madison Square, Herald Square and other central locations. Now, Vision Zero’s focus on using crash data to direct the traffic calming resources means more spending on street improvements is going to poorer areas of New York. That commitment has been bolstered by federal dollars. Vision Zero was a big winner in the latest round of federal TIGER grants.

The groundwork for a similar reallocation of Philadelphia’s traffic calming resources was laid earlier this year when City Council announced their Community Sustainability Initiative (CSI) – a commitment to using economic and demographic data to guide funding and policy priorities, born out of a suspicion that Council districts with higher concentrations of economically distressed areas are not receiving an equitable share of public investment.

Judging by the outsized share of pedestrian collisions that occur in distressed neighborhoods, a Vision Zero approach would suggest that such places deserve a larger share of the city’s traffic calming and enforcement dollars. Whether the types of interventions required by a Vision Zero platform are embraced by a City Council notorious for its windshield perspective, though, remains to be seen.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.