The U.S. adoption system discriminates against darker-skinned children

When it comes to adoption, Americans might assume that each child is treated equally. But research shows that darker-skinned children are repeatedly discriminated against.

Children who have darker skin wait longer on average to leave foster care. (Stepan Popov/Shutterstock)

When it comes to adoption, Americans might assume that each child is treated equally. But research shows that darker-skinned children are repeatedly discriminated against, both by potential adoptive parents and the social workers who are charged with protecting their well-being.

Social workers are often called upon to assess a newborn’s skin color, because skin color influences potential for placement. As a 2013 NPR investigation found, dark-skinned black children cost less to adopt than light-skinned white children, as they are often ranked by social workers and the public as less preferred.

According to Washington University law school professor Kimberly Jade Norwood, “In the adoption market, race and color combine to create another preference hierarchy: white children are preferred over nonwhite. When African-American children are considered, the data suggest there is a preference for light skin and biracial children over dark-skinned children.”

As a social worker with an interest in the social effects of skin color, I believe that the social work profession must be held accountable for its discriminatory practices.

Light skin versus dark

Regardless of race, adopting parents prefer to adopt a light-skinned child. A 1999 study at the Institute of Black Parenting, a Los Angeles adoption agency, showed that as many as 40 percent of the African-American couples expressed a preference for a light-skinned or mixed-race child, regardless of their own complexion.

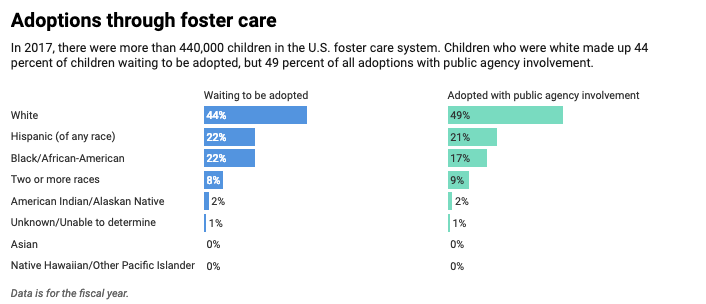

Children who are white are slightly more likely to be adopted out of foster care. Of the more than 400,000 children in foster care awaiting adoption in 2017, about 44 percent were white, while the majority were children of color. However, of those who were adopted with public agency involvement, 49 percent were white.

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services)

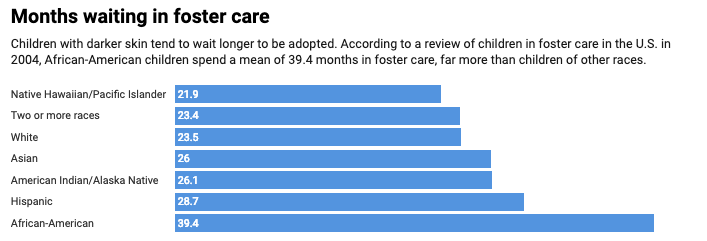

According to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 2004 data shows that children with lighter skin were adopted more quickly out of foster care. While white children waited 23.5 months on average, black children waited 39.4.

In preparing a paper on this subject in 2017, I found a 1999 report from the American Civil Liberties Union which conducted a court-authorized review of 50 adoption case files in New York City. They concluded that the practices of social workers favored children with more Caucasian features. When social workers were asked about this, they contended that it was to insulate dark-skinned children from rejection.

Research suggests that the skin color issue continues to be a problem across the U.S. A study similar to that of the ACLU’s was conducted in 2010 in the state of Michigan. This study looked at 1,183 adoptive Michigan families who adopted children from 2007 to 2009, through both public and private adoption agencies. According to the findings, 42 percent of adoptive parents’ most recently adopted children were “very fair or somewhat fair” in skin color, while 31 percent were “somewhat dark or very dark.”

Finally, research shows that it costs more to adopt a white child in the U.S. than it does to adopt a black child. According to the NPR investigation, it costs about US$35,000 to adopt a white child, absent legal fees. Meanwhile, a black child cost $18,000.

These prices, which are set internally at adoption agencies based on a number of factors, suggest that white children have a higher market value in the adoption marketplace and are more highly sought after by adoptive parents.

The dark side of adoptions

The evidence suggests that social workers do discriminate based on skin color. What’s more, private agencies that do not employ social workers no less enable skin color discrimination by referring to adoptees’ skin color.

Adopting parents may ask for a child who looks similar to them or who has lighter skin. Currently, even when skin color is not an official record, social workers are inclined to share such information casually in response to parents’ questions.

When social workers accommodate a preference regarding skin color – by evaluating a child’s skin color or by responding to parents’ questions about a potential adoptee – they are breaching their code of ethics. The official Code of Ethics for the National Association of Social Workers clearly states that social workers “should not practice, condone, facilitate, or collaborate with any form of discrimination” on the basis of race, ethnicity or color, along with other factors.

Assessing children by skin color allows for a ranked ordering, where dark-skinned children may be singled out as less valued. While it is not always a matter of formal record, children assessed as dark-skinned clearly have a different experience than white children in the adoption process.

No doubt, the significance of skin color requires it be noted in files – but, in my view, it should not be monetized. I feel that skin color should be maintained as a confidential record, unless social workers can establish a clear reason why sharing it would lead to the best adoptive outcome for the potential adoptee.

I believe that it’s important to expose the dark side of adoptions that children regardless of skin color be valued and safe from discrimination.

![]()

Ronald Hall, Professor of Social Work, Michigan State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.