The invisible women of the Civil Rights Movement

ListenTens of thousands of women participated in the March on Washington on Aug. 28, 1963. But none of the female civil rights leaders marched in the procession with Dr. King, nor were any of them invited to speak to the enormous crowd.

Instead, these women were asked to march on an adjacent street with the wives of the male leaders and to stay in the background.

The small role allowed female civil rights leaders in the activities of that day was the exact opposite of the central role these women played in planning the strategies, tactics and actions of the movement — including the march itself! In fact, many of the most iconic campaigns of the civil rights movement were coordinated by women, including nonviolent sit-ins at segregated lunch counters, forced integration of Central High School by the Little Rock Nine, and the voter registration drives of 1964’s Freedom Summer.

Let’s celebrate the legacy of Martin Luther King by learning about and remembering the overlooked women leading the struggle for equal rights right by his side.

Daisy Bates and the Little Rock Nine

Daisy Bates (1914 – 1999) was the force behind the integration of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957. She recruited, organized and supported the nine teenagers — six girls and three boys — and their families who were chosen to desegregate the school under court order. White mobs rallied at the school in the early days, hurling insults and threatening violence. Ultimately, it took the U.S. Army to escort the black students to school and keep them safe, which showed the nation that the federal government was serious about enforcing integration.

Daisy Bates (1914 – 1999) was the force behind the integration of Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1957. She recruited, organized and supported the nine teenagers — six girls and three boys — and their families who were chosen to desegregate the school under court order. White mobs rallied at the school in the early days, hurling insults and threatening violence. Ultimately, it took the U.S. Army to escort the black students to school and keep them safe, which showed the nation that the federal government was serious about enforcing integration.

It was Daisy Bates and the local NAACP who planned, coordinated and executed the Little Rock Nine strategy. Bates was rewarded for her efforts with rocks thrown through her windows, a cross burned on her roof and the financial demise of the newspaper she and her husband owned.

Segregation opponent Pauli Murray

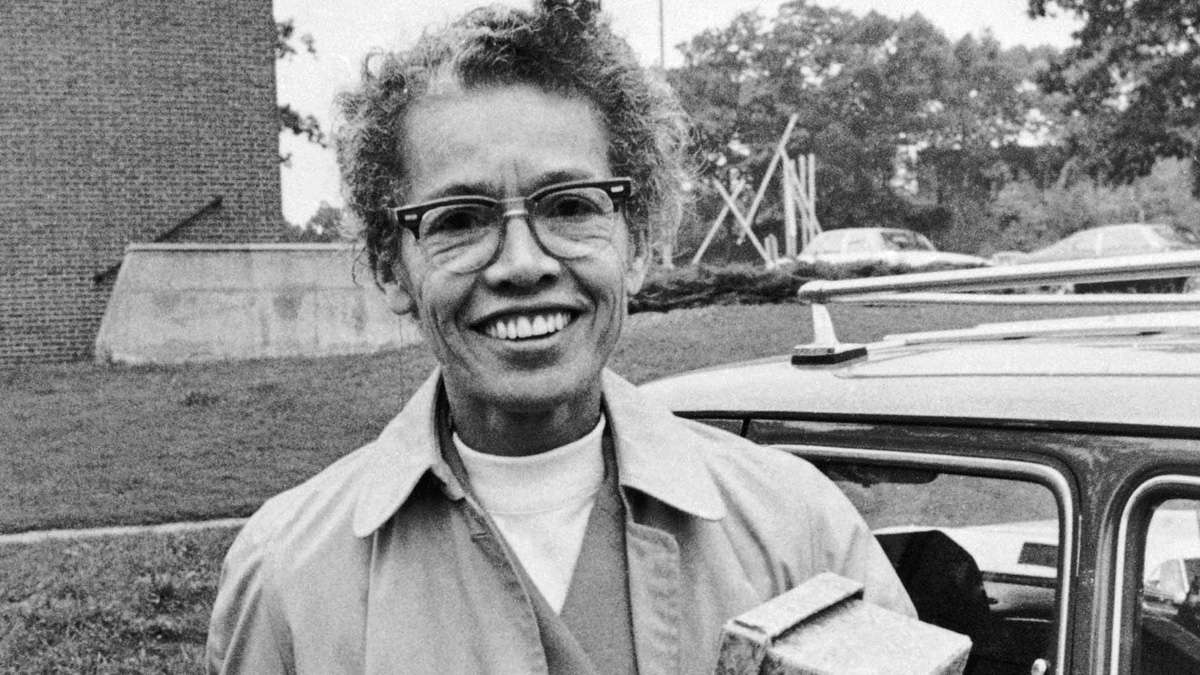

Pauli Murray (1910 – 1985) was a groundbreaking legal scholar, lifelong activist for civil rights and women’s rights and, in her later years, the first African-American woman ordained as an Episcopal priest.

Pauli Murray (1910 – 1985) was a groundbreaking legal scholar, lifelong activist for civil rights and women’s rights and, in her later years, the first African-American woman ordained as an Episcopal priest.

In 1950, Murray published a legal study of the segregation laws in the states. In it, she argued that civil rights lawyers should stop taking a gradual approach to changing segregation and should instead argue straightforwardly that segregation itself violated the U.S. Constitution. Thurgood Marshall, lead counsel in Brown v. Board of Education and later, a justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, called this book the “bible” of the Civil Rights movement.

Murray also turned her sharp legal mind to gender discrimination. In 1961, as a member of the Presidential Commission on the Status of Women, she wrote a memo arguing that the 14th Amendment to the Constitution outlawed gender discrimination as well as race discrimination. In 1963, she became one of the first to criticize the leaders of the civil rights movement for its overt sexism.

In 1966, she became a co-founder of the National Organization for Women.

Fannie Lou Hamer: every voter counts

Fannie Lou Hamer (1917 – 1977) was one of the founders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and deeply committed to helping African-Americans gain their voting rights. In the deep south at that time such activity was often met with violence. She was well known for singing hymns to keep up the spirits of the people who were putting themselves in danger to register themselves or others to vote.

Fannie Lou Hamer (1917 – 1977) was one of the founders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and deeply committed to helping African-Americans gain their voting rights. In the deep south at that time such activity was often met with violence. She was well known for singing hymns to keep up the spirits of the people who were putting themselves in danger to register themselves or others to vote.

In July 1963, she and a group of activists were returning by bus from a workshop when they were stopped, arrested and then savagely beaten. Despite this ordeal, Hamer continued her advocacy work, including organizing the Freedom Summer campaign in the summer of 1964.

Also in the summer of 1964, Hamer attended the Democratic National Convention as the vice chair of the Mississippi “Freedom Democrats.” Their goal was to challenge the all-white, anti-civil-rights Mississippi delegation to the convention as not representative of Mississippi Democrats. Their challenge drew national attention, and a speech given by Hamer was seen on national television. Her eloquence and passion changed the tenor of the debate at the convention.

Dorothy Height, champion of racial justice

Dorothy Height (1912 – 2010) was a social worker, educator and activist for civil rights and women’s rights. Among Height’s achievements was coordinating the integration of the facilities of the YMCA in 1946. She also co-founded the Center for Racial Justice in 1965. She served as president of the National Council of Negro Women from 1957 to 1997. During the 1960s, she organized “Wednesdays in Mississippi” to bring together white and black women for conversation and to increase understanding. She has been described as one of the “Big Six” in the civil rights movement.

Dorothy Height (1912 – 2010) was a social worker, educator and activist for civil rights and women’s rights. Among Height’s achievements was coordinating the integration of the facilities of the YMCA in 1946. She also co-founded the Center for Racial Justice in 1965. She served as president of the National Council of Negro Women from 1957 to 1997. During the 1960s, she organized “Wednesdays in Mississippi” to bring together white and black women for conversation and to increase understanding. She has been described as one of the “Big Six” in the civil rights movement.

Height described her experience of the sexism of the March on Washington as an “eye-opening experience.” She turned at least some of her attention to women’s rights, and in 1971 she helped found the National Women’s Political Caucus with Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan and Shirley Chisholm.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.