The campaign finance of women’s suffrage

On June 4th, 1919, Congress passed the 19th Amendment, guaranteeing all women the right to vote. It would be another year, in August of 1920, before enough states ratified it.

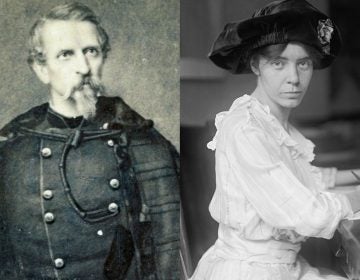

3rd May 1913: Grand Marshal Inez Milholland Boissevain (1886 - 1916) leads a parade of 30,000 representives of the various Women's Suffrage associations through New York City. (Photo by Paul Thompson/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

This story originally appeared on Marketplace. You can listen to Marketplace live on WHYY 90.9 FM Monday through Friday at 6:30 p.m.

—

On June 4th, 1919, Congress passed the 19th Amendment, guaranteeing all women the right to vote. It would be another year, in August of 1920, before enough states ratified the amendment for it to become law.

Women’s suffrage took more than seven decades of political struggle and included marches, hunger strikes, and arrests. And, like political campaigns of today, it required a lot of money. While women like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were on the front lines of the movement, there were other women working behind the scenes to fund it.

“We don’t tend to teach about the suffrage movement as a major lobbying force, a major well-funded organization in American political history — but it was,” said Corrine McConnaughy, an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, and author of “The Woman Suffrage Movement in America: A Reassessment.”

“You’re talking money on the order of what the major political parties had to spend,” said McConnaughy. “This is this is not just a few ladies sitting around signing petitions.”

Groups like the National Woman’s Party kept careful records of donations that came in from all over the country. Joan Marie Johnson, author of “Funding Feminism: Monied Women, Philanthropy, and the Women’s Movement, 1870-1967,” found records including “a typewritten 200-page list of all of the donors who gave to the organization between 1930 and 1920 and they’re recording gifts from 25 cents a dollar all the way up to Mrs. Alva Vanderbilt Belmont’s $76,000 that she gave over the course of that time.”

There were a number of wealthy women who Johnson said “clearly had outsized power through their financial contributions. And in some respects that caused tensions within the movement.”

The financial break for the suffragists came in 1914, when wealthy widow Mrs. Miriam (Frank) Leslie left her estate — worth more than a million dollars even then — to the movement. With the million or so that remained after legal challenges from the family, the suffragists did what interest groups in Washington do to this day: They hired a bunch of lobbyists.

These women descended on Capitol Hill to persuade members of Congress to support the 19th Amendment, building a lobbying operation from scratch.

“They began keeping note cards on all of the congressmen, and they would go in to see the senators and keep notes and give each other advice,” said Johnson. “Things like ‘Don’t go see a senator right before lunch — he’s too hungry and he’s not going to pay attention to you,’ but also ‘Don’t close the door when you’re in the office of a senator alone.’”

Suffragists also used the money to publish their own newspapers, cartoons, and silent films — an effort to counter the anti-suffrage messages in some mainstream press, and in popular culture.

“They are running their own propaganda machine,” said McConnaughy. “And in some sense [they] have an understanding that being seen as too politically savvy, or too politically sophisticated, or too much embedded in partisan politics might be bad for the cause.”

But not all were represented in these grand strategies. Sarah Bryner, research director at the Center for Responsive Politics, points out that the wealthy, white women who bankrolled the movement also shaped who was included in the outcome.

“So the wives of wealthy railroad tycoons and people who had access to power were the ones negotiating the discussions about who would be able to have access to power in a post suffrage world.

There were many black women active in the suffrage movement, and there are records of Madame C.J. Walker, who made her fortune in hair care, hosting meetings for black suffragists in her home in Indiana.

“She not only knew people who were suffragists and who were participating, she also was supporting it,” said A’Leila Bundles, Walker’s descendant and biographer.

But the history of the suffrage movement is rife with racism, from demands black women march in the back of a 1913 parade rather than with their state delegations, to Susan B. Anthony stating she “will cut off this right arm of mine before I will ever work or demand the ballot for the Negro and not the woman.”

And while they eventually gained enfranchisement for themselves, many of the woman leading and financing the suffrage movement didn’t push to end exclusionary practices like poll taxes or literacy tests, which continued to restrict voting for black and poor women for decades to come.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.