Part Three: A system of support, how Ontario sets its teachers up to succeed

Part Three of our Ontario series

When Erica Brunato decided to become a teacher in Ontario, she knew the road ahead would be long and steep.

“We all knew coming into this program — even just applying for the program — what it was going to be like, right? And I said, ‘I wanted to be a teacher since I was a little girl.’ So that didn’t stop me,” she said.

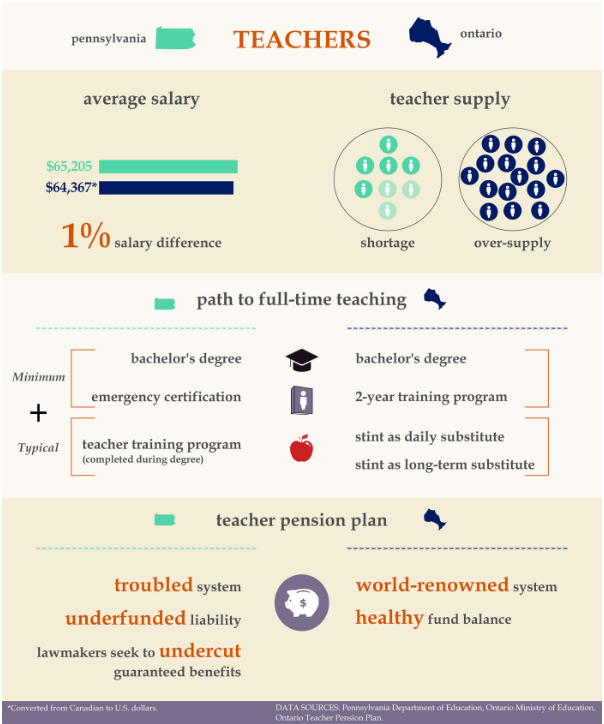

Compared to Pennsylvania, teacher preparation in Ontario is more rigorous and the job market is much more competitive.

There, students must earn a four-year college degree and then complete a teacher training program that includes a lot of classroom practice.

That training program used to be one year, but the ministry recently doubled it — moving in the direction of countries like Finland and Singapore, which are thought to be leaders in teacher prep.

For a student like Brunato, completing that program is only one in a series of steps to becoming a classroom teacher.

Because there’s currently a surplus of teachers in Ontario, students typically must do prolonged stints as substitutes, which they call “supply” teaching, before being considered for a full-time gig.

“No one right now graduates and gets a permanent teaching job,” she said. “You do your time in a supply teacher position.”

Top education officials in Canada tout this as a major boon for their system.

They say that by the time a student like Brunato is responsible for a group of students full-time, she’s proven both her commitment to the profession and her ability to put theory into practice.

And school principals largely agree.

“When I’m looking at the teachers entering the profession, they’re ridiculous. They’re masters,” said Rose Avenue elementary principal David Crichton. “They’ve got great skills in technology. They might have had a second career. I mean, they’re just outstanding people.”

Shortage in Pa.

Pennsylvania’s system is in a much different place right now. A few alarming trends suggest that teaching has become a much less attractive career.

The number of certifications given out by the state department of education has dropped 60 percent over the past few years, and the number of students majoring in education at the state’s public universities has also plummeted.

Vacancies abound in the schools that serve the neediest kids. In Philadelphia, for instance, the district struggles every year to fully staff many of its schools, even after aggressive public relations blitzes.

This means many children who need the most support are educated by a patchwork of teachers and substitutes who sometimes aren’t certified in the subject matter.

The minimum path to full-time teaching in Pa. is also much easier. College grads of any major can get emergency certifications with as little as a few weeks of training. Most of them take jobs in high-needs areas — such as Philadelphia — that perpetually have open positions.

Pennsylvania also has more colleges that confer degrees of education than all of Canada. Some say that decreases opportunities for robust quality controls.

Overall, many argue that Pennsylvania’s approach disincentivizes the best and brightest from entering the profession and then pursuing the toughest, arguably most crucial jobs.

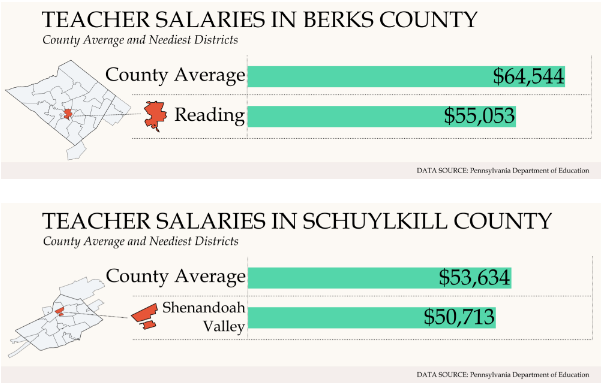

Schools carrying the greatest burdens don’t get the most fiscal support, educator ratings are in part tied to student performance, and better teacher pay awaits in posher districts.

Overall, teacher pay in Pennsylvania and Ontario is roughly equivalent, but the median average salary in the richest 20 percent of districts in Pa. ($72,793) is nearly $16,000 better than that in the poorest 20 percent ($57,059).

In Ontario, because all school funding is centrally allocated through the province, there’s much less variation in pay among boards.

Of the poorest 100 districts in Pennsylvania, 70 percent pay teachers less than their county’s average – incentivizing teachers to look nearby for higher salaries.

This, of course, makes it even harder for the most challenged districts to attract and retain top talent, and handicaps their ability provide the neediest students with stability and continuity.

The effects of this bear out when looking at the average years of service among current teachers. In poor districts that pay below county average, years of service is below state average. In rich districts, there’s significantly less turnover.

Another spot where the systems diverge is teacher pensions. Ontario’s teacher pension plan has consistently run a surplus.

In Pennsylvania, the state government has allowed pension funds to amass a large underfunded liability. And dealing with this has meant fewer resources available for classrooms, and growing calls to rethink the system — weakening retirement security for future teachers.

Building ‘capacity’

In the first story in this series, Keystone Crossroads looked at Ontario’s commitment to “equity” as a cornerstone of its approach to public education.

In the second story, we delved into the system’s celebration of diversity, and its struggles and successes in closing racial achievement gaps.

In this story, illustrated by Ontario’s views on teaching, we see another core component of the province’s overall philosophy: a commitment to building the “capacity” of its people.

A 2010 report on Ontario by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development highlighted how leaders arrived at this strategy.

“From the beginning, Ontario’s theory of change centered on the fact that school systems are easily distracted and drawn into many questions and controversies that have little or no relationship to improving student learning and educational attainment. They also believed that creating systemic change across several layers of government and 5,000 schools would require a very limited number of goals that would serve as a focus for coherent effort.”

In doing so, Ontario has eschewed much of what has become the norm in Pennsylvania — especially in regard to how it thinks about teachers.

Standardized testing happens far less frequently in Ontario, and leaders expressly discourage using scores to rank schools or shame educators.

“We know that everyone who goes to work at school each day wants to do a good job. That’s our starting point,” said John Malloy, Director of the Toronto District School Board. “And when we have factors that seem to be getting in the way of that, we try to actually go into that school to figure out…how might we actually support the teachers to meet the needs where the students are. It’s more a question of getting more precise.”

The province produces annual in-depth reports about each of its schools which — in addition to showing standardized test scores — feature a wealth of qualitative data about things such as student perspective and home life.

Anecdotally, educators in Ontario say this relative de-emphasis on standardized testing makes them much more willing to enter the profession, work in the most challenged schools, and teach holistically.

Veteran teacher Jenny Lee Shee is a great example. She recently left a cushier school in Toronto to teach at one with lower scores, and didn’t feel the need to second guess how that would impact her career.

“[Standardized testing is] not necessarily really testing what the kids can do, or what the teachers are doing,” she said. “I feel there’s a lot of problems with it, so I don’t spend too much time thinking about it.”

Lack of urgency

The flip side of this line of thinking is that educators could become too complacent with poor student results.

This idea is embraced in Pennsylvania. As such, standardized test scores are used regularly for high-stakes decisions such as firing teachers, converting schools to charters, or closing them outright.

Compared to Ontario, Pa.’s approach, especially in its neediest areas, reflects a market-reform ideology that’s centered on the idea that competition among different sectors of schools drives progress.

Some charter schools in Pa. and across the U.S. have posted impressive results for high-needs children. And, especially in the midst of large districts, these examples have shown the benefits of smaller, more nimble organizations.

And many families have embraced them as life-lines.

Other charters, though, have done little to distinguish themselves from the poor performing traditional public schools they were intended to replace.

And in failing to live up to expectations, they’ve largely duplicated an existing service while contributing to the closure of many neighborhood schools — leaving some families with fewer options.

As the previous story in this series highlighted, for all the differences in their two systems, both Ontario and Pennsylvania continue to grapple with a common, troubling fact.

Despite decades of effort, both have struggled to close the achievement gaps between their neediest students and their peers.

Ontario leaders believe that the commitment to building educator capacity will ultimately prove a wiser course. Charter schools are non-existent there, and educators don’t believe their creation would push student outcomes higher.

TDSB director Malloy is a native of Ohio who’s very familiar with U.S.-based education reform.

“The strategy of telling a school that they aren’t any good, and they have to stop, and we have to rebuild, is not our strategy at all,” he said. “In fact our strategy I would suggest in some ways is the direct opposite to that. We actually try to provide support to that school in a much more inviting hospitable way with clear expectations.”

Internal pushback

Some educators in Ontario, though, do have complaints about the province’s approach that mirror points often heard in debates about Pennsylvania schools.

Entering the teaching profession in Ontario is centered around seniority. That’s part of the reason why it takes education-school graduates so long to secure full-time employment. When new jobs open, boards must hire those who have been substituting with them the longest.

“I think it’s a terrible thing,” said Sachin Maharaj,” a high school teacher in Toronto who’s working on a Ph.D. at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE). “Just because a particular candidate has more seniority than you does not mean they are going to be a better teacher or more effective.”

Crescent Town Elementary principal Harpreet Ghuman also complained about recently losing one of his favorite young teachers during a staff reduction.

“Their seniority ranking is so low that, even if they get hired, they’re not always able to hold positions, so they get bumped out,” he said. “So, definitely, I think it can be a bit of a detriment to the system.”

Catherine Inglis, a teacher who represents the union at Rose Avenue elementary, praised the positive, productive culture that’s been fostered at her current school.

But she worries about the trajectory of her former school, and believes that a drastic staffing intervention could be of benefit.

Unlike Rose Avenue, her former school is plagued by much larger numbers of students coming from deep, generational poverty. And in the face of the challenges, she says a few “rotten apples” on the staff have been undercutting the school’s progress.

“At that school I think it was a cultural thing — some deficit thinkers among the teaching staff,” she said. “They’re certainly waiting for a couple of people to retire.”

Others complained that Ontario’s refusal to rank schools based on test scores misses important opportunities for schools to learn from one another.

Peter Cowley is a director at the Fraser Institute, a Canadian think-tank that publishes its own school ranking list.

“For any principal of a school, you got to be interested in asking the following question: ‘Out there among all the schools that are in the rankings, are there any serving similar populations of students to ours who are consistently over time doing better than we are?’” he said. “And if there are, wouldn’t it be incumbent upon that principal to go and be in touch with those other schools?”

For Erica Brunato and her classmates, there is rich debate to be had in hashing out the merits of these different Ontarian policies.

They agree, though, that it’s heartening to enter a system that prides itself on supporting educators.

And their professor, Arlo Kempf, says, this context is key when judging the quality of Ontario’s teachers and the effectiveness of its teacher preparation programs.

“If you were to swap, let’s say, five teachers from Philly with five teachers from Toronto who’ve gone through completely different training processes, are those five teachers from Philadelphia going to come here, and bring with them the challenges? No.” he said. “They’re going to come here and encounter a system that floats them up, that supports them.”

Keystone Crossroads explores the urgent challenges pressing upon Pennsylvania’s cities. Four public media newsrooms are collaborating to report in depth on the root causes of our state’s urban crisis – and on possible solutions.

‘Floats them up’

(Ian Willms / Boreal Collective)

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.