South Philly High five years later: stability replaces ‘deliberate indifference’

ListenThe costumed lions roared. The drumlines marched. Young and old mixed over traditional food, music and game.

For the second year running, the Philadelphia’s Vietnamese population held its lunar new year celebration in the gymnasium at South Philadelphia High School.

It’s a fact that many in South Philly’s Asian community would have thought impossible just five years ago.

Chief among them would be Duong Ly, who was a junior during what many consider the high school’s darkest period.

“I went to school every day, looking down, waiting for school to be over,” he said, “waiting for the day I would graduate from the school, so I could just get out.”

Ly says the school’s culture back then was one of “institutionalized violence.”

“Anti-asian, anti-immigrant sentiment and violence happened pretty much on a regular, like daily basis,” he said.

On December 3rd, 2009, racial tensions at the school reached a fever point, as more than two dozen asian students were attacked inside the building one day by a group of mostly african american students.

In some cases, kids were literally drug out of classrooms.

A subsequent attack took place after school on Broad street. In all, seven asian students ended up in the hospital.

A federal report later charged that school leaders were “deliberately indifferent” to the violence perpetrated against the school’s asian community.

But at the event held Sunday, that once marginalized community, Ly included, now says the school’s culture has been completely transformed.

‘Not about who beat whom’

Multiple voices say the changes at Southern are real and encouraging. They began with a stand taken by a few brave students, grew thanks to support from adults inside and outside the school, and have taken root thanks to a widely praised principal who decided to dig in.

But in the months and years leading up to that violent December day, a toxic school atmosphere steeped in the halls of the building.

Ly’s brother, a year older, was physically attacked twice, once punched in the back of the head without any provocation.

Bringing grievances to staff rarely yielded any results, Ly said, and often just added insult to injury.

“They went and talked to police and they were told to write the whole report in English,” he said. “There was no language support for them at all. If they couldn’t do it, then the police would just ignore them.”

Even if victims did manage to write something, there’d be no follow up, no victim counseling, and often no consequences for perpetrators.

Former student Wei Chen, also long since graduated, says some lunchroom staffers would publicly make fun of the accents of Asian ancestry students.

“And when the other students saw it,” he said, “of course they would feel, ‘Yeah, if those can do it, why can’t I do it?”‘

The most dangerous areas in the building were the lunchroom and the two places out of sight of the security cameras: the basement and the bathrooms.

So for most of Chen’s high school career, he didn’t eat lunch or go to the bathroom at school.

“Go to the bathroom before you go school. Go to bathroom after you go to school,” he said. “That’s what happened to us.”

Still, Chen says he was attacked multiple times over the years.

Teachers who worked there at the time described a leadership culture of disorganization and poor communication that led to an “every-man-for-himself” attitude.

Several factors made the situation even worse. The school’s Asian immigrant students were effectively segregated from the rest of the student body, because English language learners were clustered on the second floor of the hulking five-story building.

A boycott attracts outside eyes

The day after the Dec, 3 attacks, South Philly’s then-principal LaGreta Brown attempted to downplay what happened.

An eight-day boycott ensued, with Chen, Ly and about 50 other students refusing to attend classes.

It was Chen who decided to alert the media.

“I felt: That’s enough for the Asian community and for the immigrant students in the school,” he said.

The story went national, with criticism and blame assigned to the highest ranks of district leadership, including then-Superintendent Arlene Ackerman. At the end of the year, principal Brown, who it was discovered didn’t have proper credentials, was let go.

Talking about that day now, Chen says it’s wrong to vilify any segments of the student body wholesale.

“It’s not about who beat whom,” he said. “It’s about who let this happen in the school. When I was a student and went to the lunch room, I had people throwing food at me. When the staff saw it, when we turn our heads to them, they turned their heads away.”

Chen is also quick to add that there were many good, actively-engaged adults in the school.

“I don’t blame everybody,” he said. “There’s good teachers and there’s irresponsible people.”

Stability, at last

Otis Hackney, an African American, came in as principal the following September, leaving a cushier gig in the suburbs because he felt like he could help reshape the school’s culture.

“When I consider where we were, or where South Philadelphia High was when I first got here to now, it’s huge,” he said at an interview at the New Year’s celebration.

Hackney had been there a few years prior as an assistant principal, and says he saw then the traces of what later festered into horror.

“When I chose to come back it was to tear down the systems that fed into creating that environment,” he said.

Nancy Nyugen, executive director of the Delaware Valley chapter of Boat People SOS, a national Vietnamese outreach and advocacy organization, credits Hackney with bringing badly needed stability to the school.

On Sunday, she stood on a stage in the school gym before the hundreds in the audience, introducing Hackney through a creaky PA system.

“This place was a different place five years ago,” she said, “and your leadership has transformed it.”

Nyugen says having the new year’s event at the high school has become an emblem of what can happen when leaders fight against entrenched attitudes.

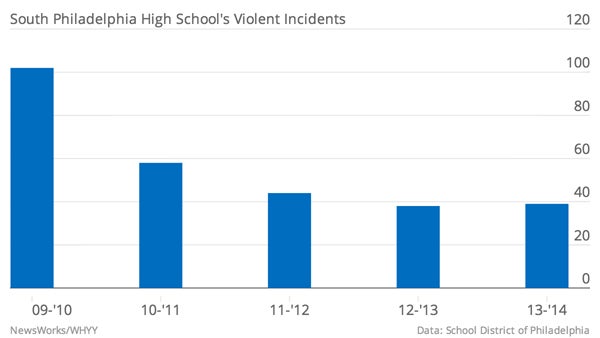

The Asian community, she says, could have pulled up stakes, but she’s proud it didn’t. And violent incidents at the school are now less than half what they were in 2009-10.

“What happened at South Philly High in 2009, it happens in degrees all over the city, and people generally flee, individually; they try to go to a different school,” she said. “But I think this is indicative of what happens when the choice that you make is not to leave but to stay and take on the harder work.”

A principal digs in

So what exactly led to change?

Hackney, who’s the first to admit that things still aren’t perfect, says opening the school’s doors to community groups like BPSOS and Victim/Witness services of South Philadelphia have had a tremendous impact.

Teachers also point to the arts-based community organizations that invested time and resources into the school, such as the Wilma Theatre, which staged a play students wrote based on their experiences, positive and negative.

The school’s English language learners are also no longer segregated on their own floor. The district overhauled Southern’s security staff and installed a brand-new $750,000 security camera system.

Another major driver of change has been the simple fact that Hackney has stuck around.

In a Philadelphia School District that’s been stripped by budget cuts – where principals and staffers are always asked to do more with less – five years is a long time.

Before Hackney, the school had four different principals in that same amount of time – far from a rarity in the district’s neighborhood schools.

Superintendent William Hite sees Hackney as an exemplar of leadership stability that he seeks to scale districtwide. He says he understands, though, the immense pressures faced by all educators in the city, pressures that often push employees to seek other options.

“They’re not in this alone,” said Hite, who said the district would work to provide its leaders with the resources they need to improve schools.

English teacher Barbara Keating, a 10-year Southern veteran, agrees that Hackney’s longevity has made a tremendous difference. Now there’s better communication, she says, and a much less insular attitude among faculty.

“What’s changed is that people are more cognizant of the energy in the building,” she said.

On Dec. 3, 2009, Keating was one of the teachers who helped shepherd Asian students to their parents’ cars after school. Other teachers, strictures of the law be damned, gave students rides home.

To Hackney, perhaps the most important driver of change has been making clear a set of expectations:

“Students will do what adults allow them to do. So if adults know that when they see certain behaviors, that behavior should be admonished immediately and publicly, so that way the victim says, ‘OK, people here care for me.’

“But then the other students know, ‘Oh, that’s not acceptable here. When that starts to happen, then you see a change in the students’ behavior.”

American dreamers

For Wei Chen and Duong Ly, all of these changes came too late.

Personally, they’ve done pretty well despite the adversity. Chen, who has been taking classes at community college, won a national peace award for his leadership that came with a $50,000 fellowship. Ly will graduate from the University of Pennsylvania in the Spring.

But Chen says they watched with sadness as peers who came to America in search of a better life have struggled to find it.

“It didn’t come true for a lot of people’s American dream,” he said. “Because many of my friends dropped out during high school because of school violence.”

Both Chen and Ly, though – who remain active in the Asian youth community – are encouraged by what they see now, and both have become role-models to the younger generation of students who were helped by their advocacy.

One of those kids is South Philly High freshman Toan Vong.

Walking the halls with Vong, it’s evident just how much the school has grown. He talks glowingly about his teachers and says he’s friendly with most of his classmates.

He admits that racial harmony still doesn’t come automatically, but says something that just couldn’t have been said before: He feels absolutely safe.

“It does take a little while, because we’re different races,” he said, “like we just don’t feel comfortable. Like I’m Asian, so I just don’t feel comfortable with other …but once you get to know them, they’re really friendly.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.