Separated at the border, the story of Andrea and her son José

Fearing MS-13 gang, she sought asylum in U.S. after being separated by border officials, she and her son eventually were reunited and now live in N.J.

Andrea and her son (pseudonyms), who are awaiting an asylum hearing, live in central Jersey. (NJ Spotlight)

This article has originally appeared on NJ Spotlight.

–

Holding On is an occasional series on the effects of the Trump administration’s drive to remake immigration policy in the United States. Part Two recounts the journey from Central America of Andrea and her son, José, their separation by border officials and their case for asylum.

Following an arduous two-week journey that included walking, buses and a boat ride, in May 2018 Andrea and her 3-year-old son José arrived at the U.S. border port of entry in Rio Grande City, Texas; she was seeking asylum because she feared the wrath of the MS-13 crime gang. Four days later, immigration officials made her place her son in a truck. Then she could only watch as he cried and scrambled to get back to her as the vehicle drove away.

After spending about six weeks in a detention facility in Texas 2,000 miles from her son, Andrea was able to reclaim José from an immigrant children’s shelter in New York. At first, he wouldn’t look at her or talk to her. Later, after they settled in New Jersey, he was afraid to be away from her for more than a few minutes. Andrea said it took almost a year for José to fully trust her again, at least most of the time.

“Our relationship is difficult at times due to our past separation,” Andrea, which is not her real name, stated in an affidavit presented to the courts in support of her asylum case. NJ Spotlight is using pseudonyms and withholding some details about her background at the request of her lawyers to protect her identity because she could still be a target of MS-13 members in this country.

The separation of children from their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border created an uproar when it came to light in the spring of 2018 that separations were occurring as part of the Trump administration’s zero-tolerance immigration policy. Numerous mental health officials have said the separations have traumatized both children and parents, and that some may suffer the effects for the rest of their lives.

Public pressure prompted President Donald Trump to sign an order officially ending the policy on June 20, 2018, and days later a U.S. District Court judge in California issued a preliminary injunction against most detentions and ordered the reunification of all those separated within 30 days at most.

Children are still being separated

Despite the injunction, the separations continue. More than 1,100 children have been separated from their parents or guardians since that injunction; all told, since July 1, 2017, more than 5,000 migrating children have been taken from their parents and some still are awaiting reunification, said Catherine Weiss, a partner at the Roseland-based law firm Lowenstein Sandler and chair of the Lowenstein Center for the Public Interest.

“We’re still getting separated kids into the system and that is because the government is taking the position that the parents of those children are not in the class protected by the injunction,” said Weiss, who also works with the New Jersey Consortium for Immigrant Children, a group of nonprofit lawyers. “I think that position is wrong.”

Andrea and her son fled to the United States at the height of the controversy in May 2018. Now in her mid-20s, Andrea has settled in central Jersey, where one of her siblings lives. She made the hard decision to leave her home in Central America because she feared for her life.

“The person I was receiving death threats from is the father of (José),” Andrea said through an interpreter during an interview at her lawyer’s office. She said she fled to the U.S. “to keep him (José) safe, that was my objective.”

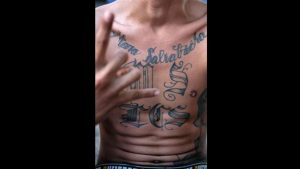

Targeted by MS-13 gang

Life in Central America became difficult and dangerous for Andrea after she began a relationship with another woman at age 16. Andrea said members of the MS-13 gang targeted her because she is a lesbian and they told her she had an “obligation” to join the gang. More than once, she was beaten by gang members, who surrounded her, punching and kicking her.

“By the end, I was lying on the floor trying to cover my face and chest from continuing to be punched and kicked,” she said when describing one beating for an affidavit filed with the court in her asylum case.

The local leader of the gang, who was in jail but still giving orders to members, learned about Andrea and ordered her to visit him.

“I was scared of him and afraid he would hurt me (or have someone hurt me) if I did not do what he said,” Andrea said in the court papers. “He had the power to order people on the outside to carry out ‘assignments’ for him.”

During a visit to the jail, Andrea said that the gang leader told her that he wanted to have sex with her. When she rejected him, he punched her repeatedly, threatened to have her killed and raped her, according to court papers.

Andrea got pregnant as a result of the rape. Still, she was forced to visit the gang leader and was raped and beaten on subsequent occasions.

“I could not refuse his order to come visit him because the gang would have harmed me and my unborn child for not obeying their leader’s orders,” she said in the affidavit.

Afraid her son would be kidnapped

After giving birth to her son, Andrea made excuses to avoid visiting the gang leader, but eventually he demanded she bring José to see him. She feared for her life and worried the gang leader would have her son kidnapped. That’s when she made the difficult decision to leave her home and her parents and make the arduous journey to the U.S.

Andrea’s father gave her some money and she set off with José in May 2018. They traveled for about two weeks until reaching Rio Grande City where they presented at the port of entry and asked for asylum. Her plan was to stay with family in New Jersey.

While the Trump administration’s immigration policies — and the family separation edict in particular — have been big news in this country, they were not necessarily major stories in Andrea’s home country. She said she did not realize when she set off that officials might take her son from her when she arrived at the border.

Andrea followed the proper procedure to gain admittance to the U.S., said her lawyer, Natalie Kraner.

“This is a very important fact,” Kraner said. “She actually presented at a port of entry. There was no illegal crossing. She did exactly what she was supposed to, and asked for asylum.”

But the policy of the U.S. Customs and Border Protection agency is to detain everyone who arrives at a border crossing without proper entry documents, even those who ask for asylum — at least until the individual can pass what is called a “credible fear” interview; the latter is used to determine whether they really face danger in their home country, said Raquiba Huq, assistant general counsel at Legal Services of New Jersey.

Customs and Border Protection data show that about 18% of all those apprehended by agents in the 2017 and 2018 fiscal years who, like Andrea, arrived at a crossing without proper documentation claimed “credible fear” to try to gain entry to the U.S.

Andrea said that she and her son were taken to a nearby processing center in Texas where she answered questions and provided documents. They were at the center for three days and were being transferred to another location when she and José were separated.

She was put into one truck, her son into another

“I was under the assumption that they were going to take us to the center together,” she said. But she went in one truck and José in another. “They didn’t tell me anything.”

The pain and fear of that moment are still hard for Andrea to talk about. Asked to describe it, she paused, then said quietly, “We were both crying because we didn’t know where he was going … Nobody explained to me what was happening.”

Andrea said she kept asking about her son but got no answers for three days. Kraner said that someone told Andrea she could lose José but would not say why. Andrea also was trying to cope with life in the detention center. She said there were about 50 women to a room crowded with bunk beds to accommodate everyone.

“There was no privacy, not even in the shower,” she said.

Andrea learned that José had been brought to a New York nonprofit shelter that assists children, including some migrants who either crossed the border alone or were separated from their families.

“He was placed in New York because there are very few shelters that can accommodate children under the age of five,” Kraner said. “Most of the tender-age kids wound up in New York.”

Eventually, Andrea was allowed to speak to José by phone, but the calls were difficult.

Crying on the phone

“He wouldn’t want to talk to me,” Andrea said. “He would always be crying on the phone. He would manage to get a couple of words out, like, ‘Hi,’ and then he would start crying.”

A social worker at the shelter told her the boy “was too upset to sleep.”

The separation profoundly impacted Andrea, as well.

“I became very depressed and anxious,” she stated in her affidavit. “I experienced terrible headaches and I couldn’t eat or sleep. Even after I was released from detention, I experienced effects of the separation — I became physically ill, experiencing headaches and fainting episodes, and I found that I couldn’t stop thinking about the separation. I would isolate myself and cry for much of the day.”

A federal judge’s injunction in the case known as Ms. L is what led to Andrea’s release from detention on July 11, 2018, Kraner said. A Texas-based advocacy organization then helped get her to an airport and paid for her plane ticket to New York, though she doesn’t know the name of the group and never met any of the members in person.

“It was a horrible experience, horrible,” Andrea recalled.

She was taken to see her son after a 41-day separation, but the reunion was difficult.

“For me, I had a lot of emotions,” Andrea said. “I was very happy to see him. But for (José), it was very hard for him. He didn’t want to be near me. He wouldn’t listen to me.”

That’s because her son blamed her for their separation, Andrea said.

Now with family members in New Jersey

Andrea and José went to live with family members in central Jersey. While their new home should have felt like a safe place, for a long time José would get upset if Andrea left him for more than a short time.

“In the beginning, he was very consistent with asking me, ‘Where are you going?’” Andrea said. “He wouldn’t want me to go work. He didn’t want me to be out of his sight. He would tell me, ‘Please don’t leave me again.’”

A number of psychologists, scientists and other professionals have warned about the effects of family separation on both children and parents. What Andrea describes follows the pattern of what professionals have seen in similar circumstances.

“Unwanted and unexpected separation from parents may have severe consequences in a child’s developmental processes and psychosocial functioning,” Cristina Muñiz, told a U.S. House Committee on Energy and Commerce subcommittee last February. Speaking on behalf of the American Psychological Association, Muñiz said, “The intense fear, sense of helplessness and vulnerability for the child associated with forced separation from their parent can lead to a state of hyperarousal, attention deficits, depressive symptoms and interference in their ability to communicate and relate to others.”

Writing for a group of scientists, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, a senior fellow with the Brookings Institute, used the term “toxic stress” to describe what immigrant children and their parents experience due to separation.

“The trauma that many of these parents and children are experiencing on American soil threatens to undermine their future development … we know that the cost to our societies can be enormously high,” Hirsh-Pasek wrote in a July 2018 blog post. “When traumatic experiences are imposed on young children, the impact on their bodies and brains can last a lifetime … Even short-term separations can be traumatic if they are sudden, unexpected, terrifying, and the child is not provided with other familiar adults who can provide comfort.”

Huq of Legal Services of New Jersey said LSNJ attorneys who are working to help young children separated from a parent wind up spending more time “just kind of sitting with them and talking to them about mommy or coloring with them” because the children are so upset and spend much of the time crying.

“Certainly, those newly separated young kids are completely terrified and out of their comfort zone,” she said. “It’s just so hard.”

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Hirsh-Pasek wrote that toxic stress “won’t simply dissipate without attention and care for both the children and the parents,” noting that many parents experienced trauma in their home countries and on their journey to the U.S., even before their children were taken from them.

Andrea has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, Kraner said, yet getting Andrea and her son health and social services can be difficult because there are not many providers who speak Spanish where they live.

Andrea has been granted permission to stay in this country and to work pending a hearing on her asylum claim, but due to backlogs in the immigration court system, her case will not be heard until the fall of 2021. Her attorneys think she has a good chance of being allowed to stay because of the violence and threats she endured. Data on all cases, however, show that only slightly more than a quarter of close to 53,000 asylum applicants who claimed credible fear in the last two fiscal years had their applications granted.

While heart-wrenching, Andrea’s story so far has a happier ending than many others. Some children were separated from parents for far longer, others remain in youth shelters throughout the country, at least temporarily, and still others remain sheltered or are in foster care because their parents either have not been located or were sent back to their home countries.

“There are now efforts to find those families,” Weiss said. “Many, many of the parents were deported and we, as the lawyers in that case … are looking for the parents of those children to inquire about reunification.”

Weiss is one of the lawyers involved in the Ms. L v. ICE class action lawsuit, which began as a single action on behalf of an asylum seeker from the Democratic Republic of Congo separated from her 7-year old daughter for several months and by 2,000 miles while the woman was detained by immigration officials. On June 26, 2018, U.S. District Court Judge Dana Sabraw granted a preliminary injunction against detentions unless the parent is “unfit or presents a danger to the child,” writing, “Extraordinary relief is requested, and is warranted.” He also ordered federal officials not to deport a parent without their child unless the parent agrees.

Thousands of children

From July 2017 through the date of the injunction, 4,370 children had been separated from parents. Since then, according to the latest court figures, at least another 1,100 have been held apart from their parents, Weiss said. The American Civil Liberties Union and other lawyers involved in the case are asking Sabraw to enforce the preliminary injunction, which they say the U.S. is violating. The judge is considering the case.

“The government alleges that there is criminal history in the parents’ background,” Weiss said in explaining why most of the separations continue to occur. “They also assert doubt about heritage. In some cases, they think it’s not the parents, but somebody else. And, in fact, we have lots of children who are raised by grandmothers, older sisters, uncles and so forth.”

Customs and Border Protection officials say they are complying with the injunction and that child separations that are occurring now are permitted by the injunction or other laws, including the federal Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act.

Any undocumented child brought to the border by someone who is not a parent or legal guardian, even if that person is another family member, is processed as an unaccompanied child and placed with a family member or friend already in the U.S. or in a youth facility contracted by the Department of Health and Human Services. CBP does not consider these to be family separations.

Officials also contend they can separate a child from a parent or guardian to ensure the child’s safety both under the anti-trafficking law and the Ms. L case when:

- The adult presents a danger to the child;

- The parent has a criminal history, an outstanding criminal warrant or is criminally charged on narcotics smuggling or other activity related to entry into the country;

- The adult has a communicable disease;

- The guardianship claim may be fraudulent.

Kraner disputed the government’s assertions that on-going separations are only being done to protect children.

“We’ve seen cases where mom or dad had a conviction for a $5 destruction of property 20 years ago where they’re separating the child,” she said. “That really has nothing to do with safety.”

Proud parent of a kindergartner

In the case of Andrea and her son, now nearly 18 months after their ordeal, Andrea can say that life has improved for her.

“I can’t say it’s 100 percent but it’s much much better” and safer than in Central America, she said. Like a typical proud parent, she showed off a first-day-of-school picture of José sporting a backpack about half as tall as him. “He’s very happy,” Andrea said of José, who started kindergarten in September.

Still, she said life in the United States is harder than many in Central America imagine it is. But Andrea is doing whatever she can to do what’s best for her son.

“I don’t need to have luxuries in life,” she said. “I just need to provide a better future for my child.”

Part One of the Holding On series tells the story of “Dreamer” Itzel Hernandez, one of thousands of young undocumented immigrants in New Jersey who were brought to the United States as children.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.