Scientists mobilize to account for rise in mange among Pa. bears

Bears in Pennsylvania are struggling with mange they can't seem to kick. Scientists are studying what's unique about the disease in the state.

Bears in Pennsylvania are struggling with mange they can't seem to kick. (Brandon Wade/AP Images for The Humane Society of the United States)

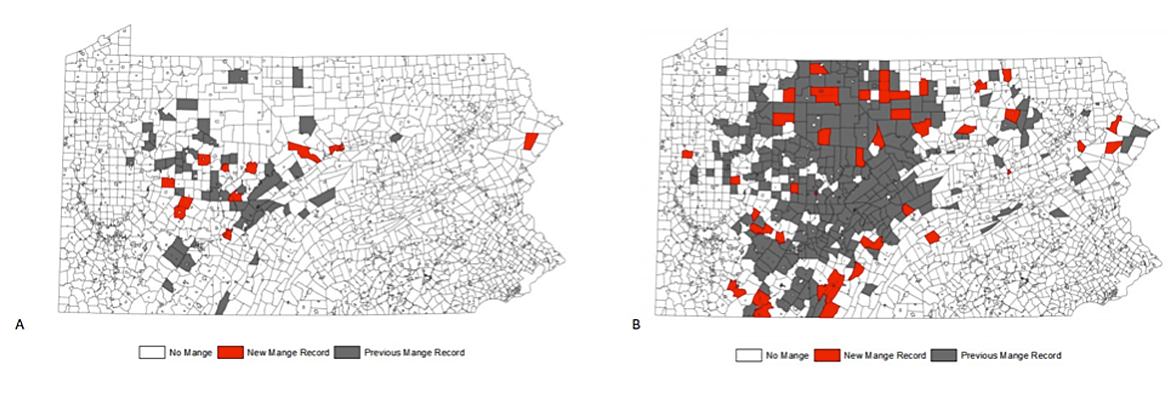

A surge in the number of Pennsylvania black bears with mange has researchers baffled.

From 2014 to 2017, about 230 black bears were euthanized because of the skin disease caused by mites. Bears all over the country contract mange, though usually the animals can fight it off.

But the bears in Pennsylvania are getting secondary infections, their immune systems are challenged, and life-sustaining behavior — such as an ability to forage efficiently — is changing. In at least one case, a mother bear abandoned her cubs because her mange prevented her from properly hibernating.

In the past few years, scientists have learned that the mites affecting bears in the Keystone State differ from those that mangy bears usually carry. This species — the sarcoptes mite — commonly appears on dogs, coyotes and other canids.

And that might be the key to what’s going on, said Erika Machtinger, lead researcher on the Pennsylvania State University project.

“One of our hypotheses is that the mite has actually jumped hosts from canids to bears,” she said. “Because it’s a new parasite on a new host, it hasn’t established a good relationship, and the bears’ immune systems can’t handle it. They don’t know how to deal with it.”

Human encroachment may be to blame for the mite migration. As canids and bears are squeezed into smaller, more fragmented parcels of land, the animals’ dwindling habitat could be allowing the jump to occur.

Pennsylvania Game Commission staff intend to collar 36 bears in three groups so scientists can study their behavior, ecology and immune systems. Healthy bears will make up the first group; bears with moderate mange will make up the second; and the third will consist of mangy bears dosed with medication.

The first bear was caught Thursday morning.

The work is to protect animal welfare, said Mark Ternent, bear biologist with the commission. At this point, he’s not concerned with bear populations — at 20,000, it’s the highest in modern times. Last year in Pennsylvania, hunters harvested more than 3,400 bears; cars hit another 400 bears. For now, mange is a minor mortality factor. But Ternent said he hopes to identify effective tools for helping the animals.

“Certainly a bear with no hair or a bear that’s emaciated catches the public’s attention. That’s something we hear about,” he said. “You know, ‘Can we help this animal?’ ”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.