Reports: Stationing police in Philly schools costly, causes trauma for students of color

Some parents of kids in city schools firmly in favor of the police presence.

Listen 2:58

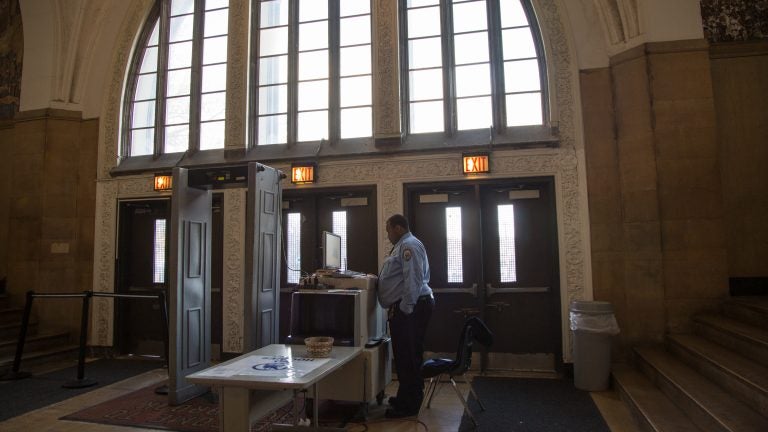

A metal detector and an x-ray machine sit at the entrance of Overbrook High School in Philadelphia. (Emily Cohen for WHYY, file)

The Advancement Project and the Alliance for Educational Justice want police out of schools, according to their new report.

The advocacy groups believe school police officers create a hostile environment for black and brown students and contribute to the trauma many experience outside of school.

Philadelphia was among the cities featured in the report, but idea of removing school police for some city parents is just unthinkable.

Terri Seward, whose daughter attends Bartram High School in Southwest Philadelphia, isn’t buying the argument that school police create a prisonlike atmosphere. She said those officers are a necessity.

“It’s a little bit comforting to me to see [the] presence of police here,” she said. “I would want to see them here. And that’s because of the environment that we live in. Unfortunately, that’s where we are.”

Robin Roberts, an active parent at Carver Engineering and Science, agreed with the report findings that school police officers can present a false sense of security while criminalizing students.

She said keeping the peace in schools has a different meaning for some students.

“That is something we hear in the black and brown community all the time, keep the peace,” she said. “But what it really means is we keep people in their places.”

Over the years, however, the district has worked to address such concerns.

As educators have moved away from zero-tolerance discipline, they have embraced trauma-informed training for faculty and school police, said Lee Whack, a district spokesman. That approach takes into account traumatic experiences students have had either inside outside of school when figuring out what to do when a student’s performance, attendance or behavior become a concern.

They’ve increased the number of school counselors and nurses, while implementing a diversion program to help reduce student arrests.

And, in partnership with student advocacy group Philadelphia Student Union, a member of the Alliance for Educational Justice created a process for students and parents to file a complaint against school police officers whom they feel abused their power.

The process was prompted by an incident used in the report as a case study, where one of their members, a student at Ben Franklin High School was allegedly attacked by a school police officer.

Whack said school police are key to the improvements in city schools.

“I would say that, here in Philadelphia, with the evolved role that we see school police having, we are seeing certain things working,” he said.

Spending priorities questioned

But some education advocates want to see more investments in students and staff.

The district has budgeted about $30 million to employ more than 350 school police who for a few years have outnumbered school counselors or school nurses. Even as the number of nurses and counselors rise, advocates say the district still has an imbalance.

And recent reports on unhealthy conditions in school buildings seem to fuel the argument for focusing on investing in schools instead of police.

“Once you start looking at the larger spectrum of the issues that exist within schools, I would have to say that student safety is very, very high,” said Julien Terrell, the executive director of Philadelphia Student Union.

“I won’t say that the presence of school police officers is actually meeting that need, though.”

Whack said he understands the concerns some may have about school police officers, but there is a demand for their presence in schools.

And even if advocates were to get their way, Terrell said, removing police from schools is a long-term commitment that requires a plan. Doing so overnight would be “irresponsible.”

Either way, it doesn’t seem likely school police will be leaving Philadelphia schools any time soon.

Sharon Childs, another parent at Bartram, said whether a school adds police or counselors, safety is not guaranteed.

“I just pray my kid is safe and makes the right decisions when they’re not with me, and go from there,” she said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.