Covering cannabis: Four takeaways for journalists reporting on pot and communities of color

The Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists hosted a workshop for journalists on covering cannabis in a new legal, cultural and economic landscape.

Imani Dawson moderates a panel with William Cobb, David Nathan and Desiree Ivey, at a cannabis in the media workshop at WHYY. (Bastiaan Slabbers for WHYY)

For a long time, if you read a story about marijuana in the newspaper, it was likely to be about crime. You wouldn’t find pot coverage in the business or the health sections. But as states have legalized marijuana for medical use over the past decade and more recently for recreational use, its context has changed: Marijuana is a multimillion-dollar industry. It’s a small-business generator and an area of growth for medicine.

Last week, Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf announced his support for the legalization of marijuana. Attorney General Josh Shapiro followed suit. But some are worried that the way we talk about weed hasn’t caught up to its newfound cultural status — the old narrative came at the expense of people of color, who are disproportionately affected by marijuana’s criminalization.

How will those communities be centered as the conversation shifts? Wednesday night, a group of journalists supported by the Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists came together at WHYY to discuss how marijuana coverage should adapt to reflect the changing culture, economy and social context of cannabis, without marginalizing communities of color.

Here are four takeaways from the training:

Keep history in mind

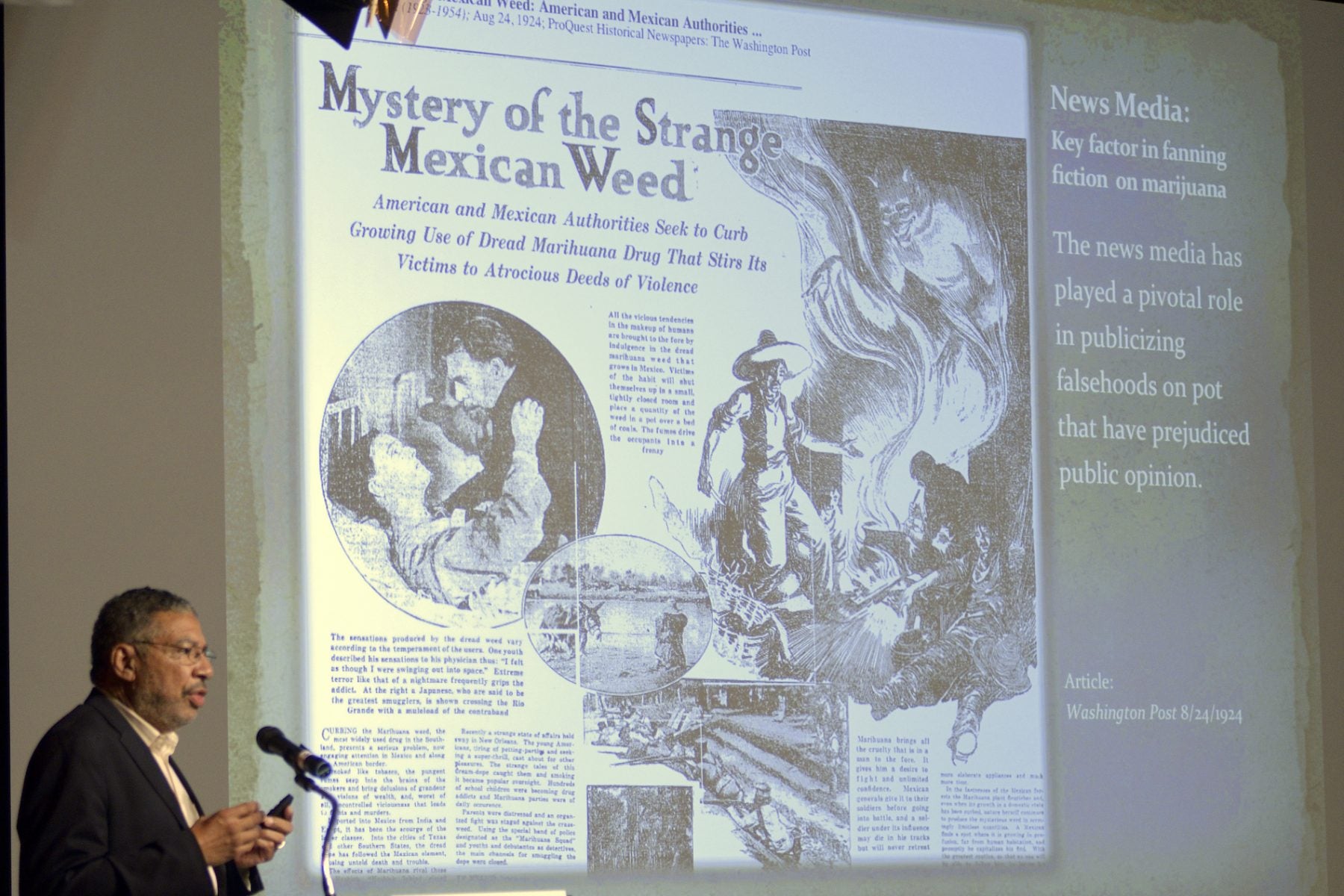

When weed was illegal, the people who used and sold it were framed as criminals. Discriminatory drug policies of the 1980s led to disproportionately high incarceration rates among communities of color, a trend that many state and local governments are trying to undo now by reducing sentences for low-level drug crimes. But historically, the association between black and brown working-class people and marijuana use has been a negative one.

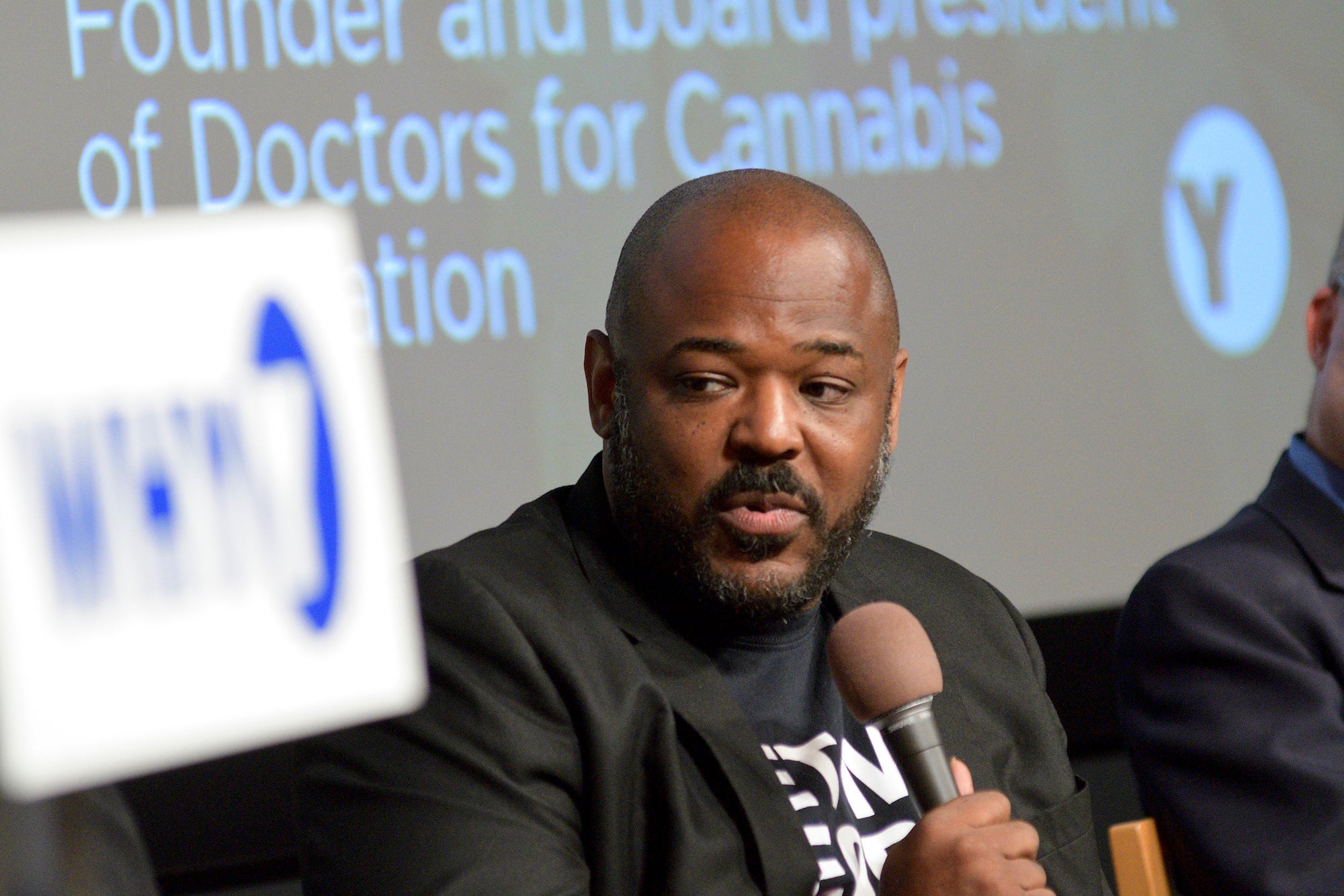

Now that weed is more mainstream, those who sell and grow are considered entrepreneurs. But journalists don’t always acknowledge that contradiction, said Bill Cobb, former deputy director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s Campaign for Smart Justice.

“For everyone whose back the industry was built on to be excluded — it’s extremely frustrating,” Cobb said.

It’s difficult for poor and working-class people of color, many of whom may have served time for drug offenses, to become involved in the legal marijuana industry because of their past criminal records, he said. The financial barrier to entry for starting a small business in the marijuana industry is high. Cobb himself served more than six years in state prison and stressed that by pointing to the hypocrisy that someone who was charged with selling weed when it was illegal is now unable to do so legally, journalists can help change the narrative.

Take the reporting seriously

In 2016, Massachusetts residents voted to legalize marijuana. Voters demanded a well-regulated recreational marijuana market. So when he questions public officials, reviews government policies, and digs into financial records, Boston Globe cannabis reporter Dan Adams feels he’s holding the authorities to account for that mandate.

Adams suggested that reporting on weed is too often reactive to new laws, policies, and bans coming down the pike when it should be proactive. He said marijuana coverage warrants a full-time reporter, who can build sources, know the beat inside and out, and ask the right questions.

He gave the example of two different styles of vaping devices used for marijuana consumption: Research shows the health impacts of each is very different, but all were banned last week in response to a series of lung illnesses and deaths related to vaping. Armed with the research, a marijuana reporter could question with authority whether the policy was truly evidence-based, but a business reporter parachuting in might not have time to take such a nuanced approach.

Adams said raising the bar for story quality fuels healthy competition in local news markets.

“It’s much harder in Boston to write a stupid story about marijuana because you’re surrounded by good stories, and you’d look stupid,” he said.

He urged journalists to use all the traditional tools in a reporter’s toolbox for scrutinizing the marijuana business: campaign contributions from industry players to local politicians; zoning laws around dispensaries; which people licensing requirements are designed to benefit, and who they exclude. He cautioned reporters not to fall for authority bias by simply trusting new policies without scrutinizing the research that backs them.

Mind the language

It can be hard to resist puns about smoking marijuana in headlines, but doing so can ensure that the practice remains in the realm of a joke, instead of being considered a real economy with real impact, Adams said. While it might seem like puns will lighten the tone and make an audience more comfortable with the material, so many use marijuana every day in this country for such a variety of reasons that making puns can actually end up alienating people, he said.

It’s not just jokes. Terms like “black market” should be avoided, said Imani Dawson, who runs her own communications company with a specialty in cannabis coverage. She said the term reinforced the notion that when people of color use marijuana it’s illegal, but when it’s done in spaces that are above-board — from which people of color are often excluded — it’s legitimate.

“If we’re fighting for inclusion, we don’t want to label the pioneers, in terms of getting people access to the plant, [as] just drug pushers,” Dawson said.

Center people

Don’t sit at your desk and wait for pitches from CBD companies to flood your inbox, said Boston Globe’s Adams. Come back to your newsroom reeking of weed once a week, he suggested, half-joking.

“Think of how far a teetotaler would get reporting on brewers,” Adams said.

Figure out what’s happening in communities using cannabis. As with anything, the people with the most lived experience are experts.

The ACLU’s Cobb added that fuller narratives with long arcs can capture complexities necessary to understand the way marijuana is changing culturally and economically. He said tracing an individual’s trajectory with marijuana distribution, the criminal justice system, and an attempt, whether successful or not, to get back into the industry, can be the best way to demonstrate how the system continues to exclude communities of color.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.