Remembering D-Day and the complex medical system that saved the boys

Seventy years ago, far from the beaches of Normandy, my grandfather, Captain Charles Felt, did his part. He was a dentist waiting for the wounded to arrive at a hastily constructed military hospital an hour outside of London — a small corner of the most quickly built medical system the world had ever seen.

Eighty miles south of him on the English coast, dozens of troop ships headed across the channel for France, though there were no soldiers on board. Instead, the LSTs (for “Landing Ship, Tank”) carried some 30,000 stretchers, 96,000 blankets and tons of supplies — blood, dressings, splints to name a few — for the 160,000 allied troops that would soon land at Normandy.

The troops arrived, of course, and down they went, many of them — bodies once strong, now vulnerable — with burns, fractures and blast injuries, to say nothing of the penetrating wounds to the head, face, neck and extremities. Several just-arriving soldiers had to load the wounded onto their boats before disembarking themselves.

Medics on the beach applied basic first aid and put the “transportable” — wounded that could wait for definitive treatment — onto the LSTs that had carried the blankets that now covered them. Across the channel at English ports, the soldiers were loaded onto trains destined for the more than 150 American-built hospitals across the countryside — one of which stationed my grandfather.

A battle to save lives

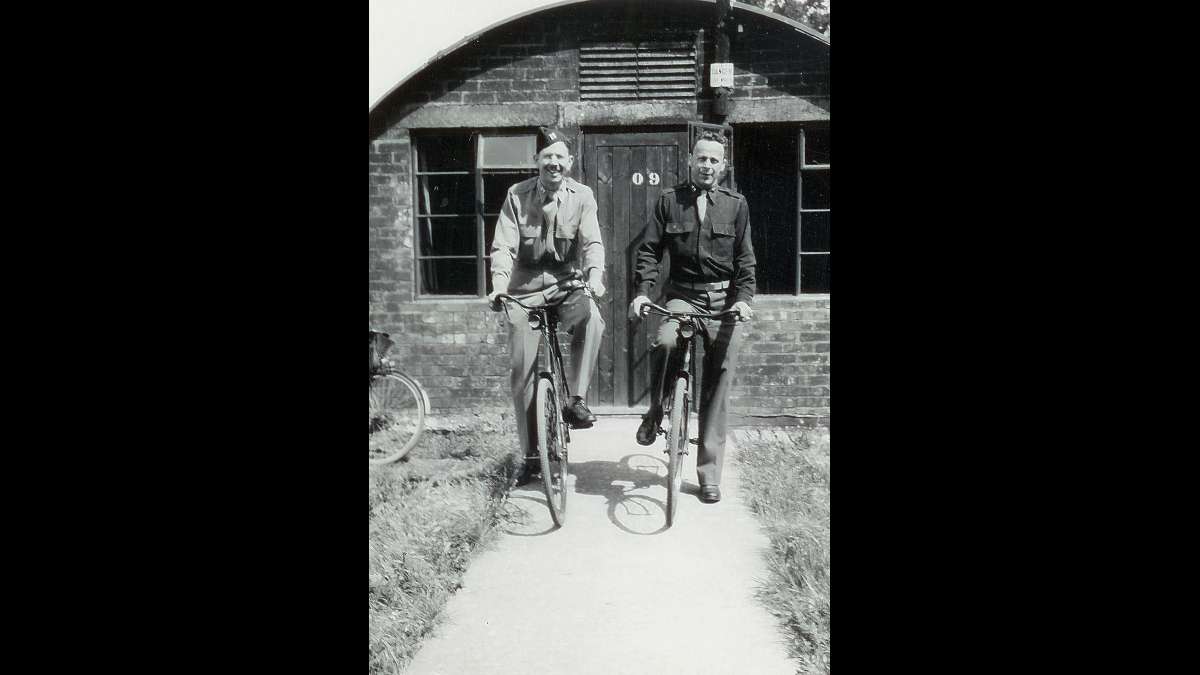

He and 500 other doctors, nurses and orderlies would finally receive the Normandy wounded five days after the invasion, on June 11. Victory for the 186th General Hospital meant getting the soldier into a bed within a half hour after his arrival at the Fairford train station in the Cotswolds.

“Doctors and nurses consider this time as their actual battle participation,” one medical official wrote. “All work long and hard hours on receipt of the casualties.” (Often working 14-hour-long shifts.) There was but one death that month reported by the hospital, which resembled nothing but a small city.

The 186th was built on a 91-acre former deer park, with 158 prefabricated, military-style buildings that housed surgical wards, a rehabilitation center and a dental clinic. There was a post office, beauty parlor and barber shop. While there was a radio “in every ward and dayroom,” a parts shortage made it impossible to “meet the musical demand.”

By the end of 1944, six months hence, there would be eight courts martial at the 186th General as well as five AWOLs (absent without leave) and 53 punishments. The chaplain would make 1,500 weekly contacts with patients. And in all, the hospital would take in and discharge more than 7,000 patients — from the severely disfigured to the traumatized, afraid of his own shadow.

Years of trauma

My grandfather, born in Mendon, Missouri, died nine years before I was born. He was a small-town Midwestern dentist before the war and had studiedmaxillofacial surgery in Kansas City. So the day the wounded arrived from Normandy, he helped the surgeons. He anchored metal posts into jaws that had been shattered by bullets; stitched together shrapnel-torn cheek muscles; pulled out stumps of once perfect teeth.

According to the hospital’s annual report I found in the National Archives, Captain Felt and his staff worked on more than 5,200 soldiers during the last six months of 1944 — an average of one patient every half-hour. They wired 17 jaws, sutured 34 mouth wounds, splinted eight, filled 1,345 cavities, pulled 973 teeth, and constructed 80 eyes: dentists were adept at painting and fitting prosthetic eyeballs made from the same resins used to fashion dentures.

Shortly after D-Day, Captain Felt transferred to a nearby hospital, the 96th General, and a month later, to the 55th General. In May 1945, the hospital crossed the English Channel and set up in Mourmelon-le-Grand, France. He remained in Europe after the war and worked in the 12th Field Hospital at the Citadel in Liege, Belgium, taking care of German prisoners and homeless civilians.

He wrote to my grandmother Trudy in Salem, Missouri, about his unhappiness that he couldn’t leave Europe. He sailed from France in April 1946, and finally came home to his wife and daughter — my mother Connie Jean, who was 6 at the time — with a puppy, “Midge,” smuggled in his fatigue jacket.

Building a new hospital system

On this 70th anniversary of the invasion, one doesn’t hear much about the ones behind the lines that day. Instead, there are the stories of the heroic infantry men, clamoring up the beach with bullets whizzing by. But the scope and ambition of the medical system was an astonishing part of our victory as a nation. Planners knew that treating the wounded among the first soldiers onto the beaches at Normandy would be hasty and incomplete, if it was possible at all — not to mention the nearly 1 million more expected to be in France by the end of June 1944.

Planners estimated that doctors and medics would treat and evacuate — by small boat-trucks (DUKWs), LSTs, British-supplied hospital ships and aircraft as available — more than 7,200 on D-Day itself with another 7,800 in the following two days. (About 450 would be too wounded to travel.) Each 330-foot-long LST — designed for troops, trucks and tanks — could carry more than 300 wounded soldiers.

On D-Day, for instance, LST No. 496 arrived at Omaha Beach and was unloading when small boats tossing in the choppy sea came alongside full of wounded. No. 496 spent three days and nights off the coast — its medics treating men and sending them back to fight. The others — about 100 — made it to England on June 10 with just one death, an accident. It was LST No. 496’s only evacuation trip. On her second voyage, she hit a mine in the Channel and sank.

After the evacuation to England, military planners needed to transport the wounded into the interior hospitals. The British had a rolling stock of 39 hospital trains to be staffed entirely with U.S. medical personnel. Each train held 256 patients with 16 cars, including one for officers, nurses, orderlies, kitchen, dining, surgery and pharmacy.

Then planners needed hospitals to accommodate more than 50,000 patients — a system that could easily move across France with the Army. Within about five months, they had to assemble and place on-site equipment for 30 general hospitals (1,000 beds each) and 20 station hospitals (750 beds). But the most efficient supply depot in late 1943 took three months to put together just over half of one 1,000-bed assembly.

“We’re in trouble,” one official wrote. “This was roughly the equivalent of shipping about 12 complete New York City Bellevue Hospitals, except the buildings.”

As if this were not enough, the depots would have to outfit still more incoming units, complete the equipment of organizations taking part in the assault, and pack dozens of waterproof maintenance units to supply the invasion force in its first weeks on shore. With the existing organization, personnel, and methods, officials feared these jobs could not be done in time. But they reorganized and threw in more resources — assembling many hospitals in the U.S., shipping them to England.

My grandfather trained with his hospital in the middle of Kansas at Camp Phillips. They crossed the Atlantic together on the same ship, the Esperance Bay, and were up and running at the 11th hour — barely a month before the invasion. But they pulled it off. By the end of June 1944, they admitted 922 soldiers, and more than 1,400 in July. After trial and error, their annual report noted that they were able to “dispose of as high as 464 patients a day without any dislocation of the hospital work and with minimal confusion.”

Indeed, by war’s end, the U.S. and its allies had trained a total of 324 hospitals with 422,000 beds, both fixed and mobile, in Africa, the Mediterranean, Europe, and the Pacific. And thanks to advances like penicillin, the number of deaths from wounds was cut in half compared to the First World War.

No peace at home

The large successes overseas turned out to be non-transportable to home, for countless of the Greatest Generation, and especially my grandfather. The war changed him irrevocably: My grandmother told me she “saw it in his eyes” the day she picked him up at Union Station in St. Louis.

Though he returned to his growing family, he was upset that he was not among the many others who had returned the year before. He was slowly going blind — following the sudden onset of neuritis in his left eye. While his dental practice was successful — he built a new house and purchased cars and boats — he was restless in the day and sleepless at night. He drove his cars fast and had nightmares. He turned, in part, to the sedatives he prescribed to his patients and died in a single-car accident 11 years after his return, just a day after the anniversary of his induction into the Army.

I wondered about the effect treating wounded American boys might have had upon my grandfather, by most accounts a gentle and easygoing man known affectionately as “Blacky” for his five-o’clock shadow. I called Jonathan Shay, a psychiatrist at the Department of Veteran Affairs, who has written several books on trauma and veterans. “A trauma dentist — in a sense what your grandfather was forced to do likely without a shred of training — has a constant diet of facial disfigurements,” Dr. Shay said. “Whole jaws shot away, sides of faces blown off, people with their eyes destroyed. It is horrific to think of what he likely had a steady diet of and could not get away from.”

I told Dr. Shay a story my grandfather had told my grandmother. He was walking outside when a shell exploded near him. He hit the ground and was covered in what appeared to be blood. It turned out to be mud and water from the blast. Dr. Shay replied that current thinking about trauma includes even the terror of dying or being wounded, though I couldn’t help but feel my grandfather’s experience seemed insignificant when placed against the experiences of thousands of infantryman actually wounded at Normandy.

I asked my great aunt about him. She said that he spoke to her about “triage” of mortally wounded patients at the war hospitals under which he served. “He told me that he had to make decisions in several cases, decisions that would end someone’s life. It really bothered him more than I had seen him bothered. Though he spoke about it as if it’s just what you had to do.”

The ones who remember

In April 2000, I attended a reunion of a dozen veterans from the 186th. It was held in Evansville, Indiana, home to the largest inland producer of the LST during the war.

One medical officer in his late 80s came from California. “At the hospital mess hall, I always sat at the dentists’ table,” he said. “We called ourselves ‘the intellectuals.’ We used to talk about the funny papers. Then a nurse — Ariel Powers, she was from Cedar Rapids, Iowa — did a dance out by the statue on the lawn. It was unforgettable.”

Another veteran, from Michigan, said that when my grandfather, Dr. Felt, worked at the dental clinic with Dr. Chott, he pulled a prank. “When a patient came in, the receptionist would ask, ‘Would you like to be felt or shot?’ Everyone got a kick out of that.”

One veteran came to the reunion from Philadelphia. On D-Day, he was painting a sign announcing a dance that Saturday night. The hospital had a stage, a movie theater and a nine-piece dance orchestra. “That went down the drain when I turned on the radio,” the technical sergeant said. “The next 10 days, well, it was like a living nightmare.”

He helped carry the litters to the operating room — stacked until the surgeons could get to them. “You’re not talking just about D-Day, you know, because to us that was just the beginning,” he said. “We spent days and days and then months and months and then years and years getting those boys back to the lines. And when one went back, here come a hundred more.”

Another veteran, Vincent Tricomi, said, “It was hard on all of us. When you get so busy, you don’t have time to step back and say, ‘That is terrible.'”

Dr. Tricomi, who was in charge of an operating room during the war, died in 2011. He came up to me later at that reunion in 2000. “Listen, I mean the poor young fellows were getting killed, and we were back from the front a little bit,” he said to me, holding my forearm. “So we were trying to do our part. That’s all. You know, we basically felt the war through them.”

—

Michael Carolan was born in Kansas City. He teaches writing and literature at Clark University. He lives in Western Massachusetts with his wife and two children.

A longer version of this article appeared in The Massachusetts Review, autumn 2008, and was awarded an Atlantic Monthly Writing Award.

Sources:

186th General Hospital Annual Report, 1944. National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. 103 pp.

“U.S. Army in World War II, Technical Services, Medical Department: Medical Service in the European Theater of Operations.” By Graham A. Cosmas and Albert E. Cowdrey. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, 1992.

“Return to Duty: An Account of Brickbarns Farm, Merebrook and Wood Farm, U.S. Army Hospitals in Malvern, Worcestershire, 1943-45.” By Fran and Martin Collins. Warwickshire, U.K.: Brewin Books, 2010.

WW2 U.S. Medical Research Centre

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.