Record turnout to kick off West District Plan

Last Thursday, at West Philadelphia High School, the Philadelphia City Planning Commission commenced its second to last district planning process.

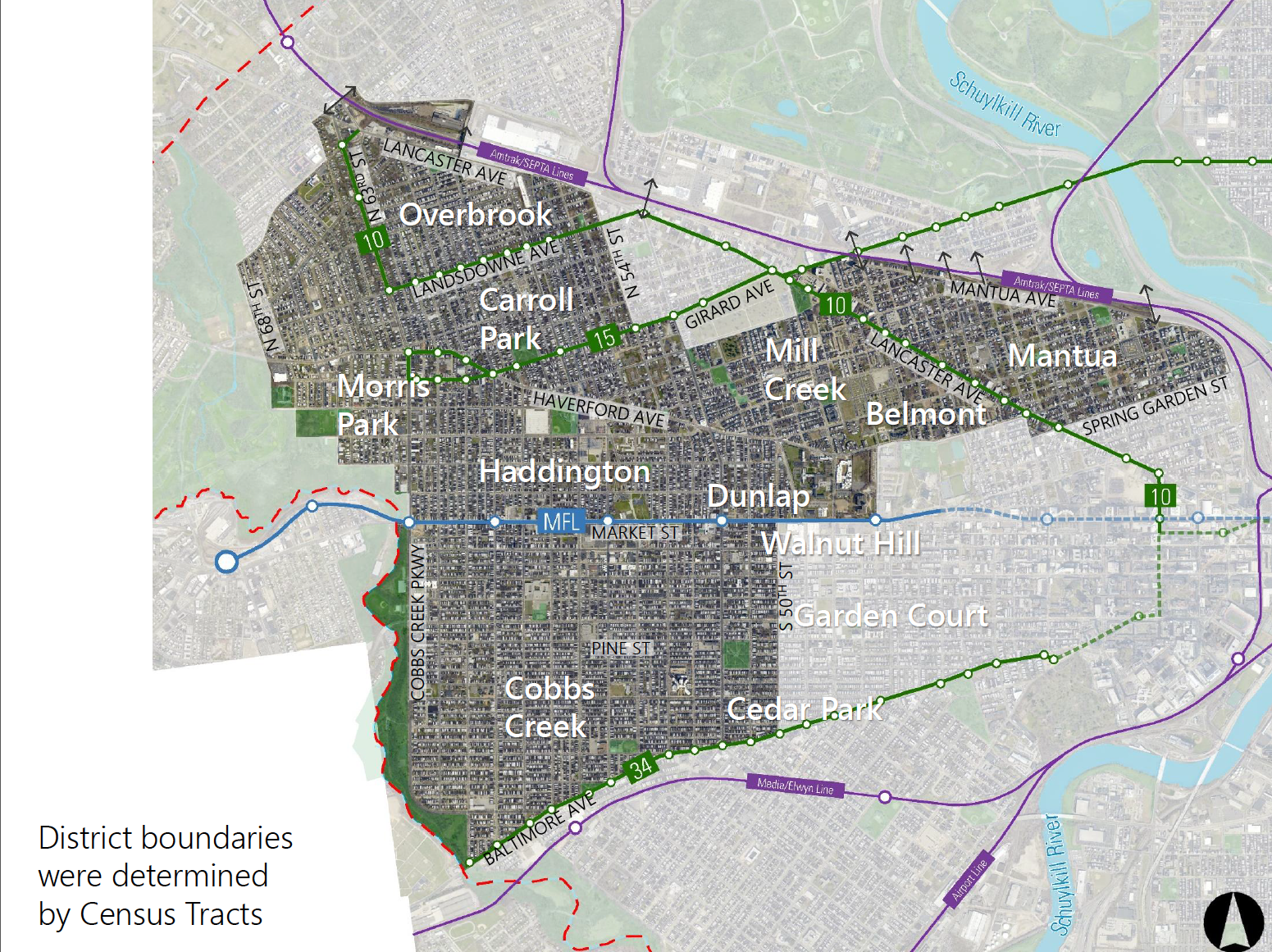

The commission began crafting district plans for every corner of the city in 2011. Over the course of three community meetings, commission staffers work with residents to hammer out the priority areas and issues for each region in the city. Five and a half years later, only three districts remain: the North District (undergoing the public engagement process), the Upper Northwest (set to begin in the fall), and the West District (which began last week).

The inaugural West District meeting enjoyed the largest turnout ever recorded, with almost 300 attendees. Community members packed the school’s cafeteria and its surrounding hallways. A dozen tables were covered with maps of the district. Residents crowded around each one, arguing companionably—and occasionally heatedly—about West Philadelphia’s strengths and challenges.

There were some tense moments over the course of the 90-minute gathering. Numerous attendees were overheard denouncing the University of Pennsylvania’s influence on their neighborhoods. Jobs were brought up again and again as a pressing need in the community, with many people expressing frustration that Mayor Jim Kenney’s equitable economic agenda hadn’t yet reached their neighborhoods. (The soda tax, notably, never came up although the mayor’s Rebuild initiative was the subject of much speculation.)

One man, visibly agitated, said he didn’t understand the point of the exercise. Where was the mayor? Where was councilwoman Jannie Blackwell, who has represented much of the district for a quarter century?

“We can’t make them do anything, but we can be very persuasive,” said Laura Spina, one of the planners in charge of the process. “This kind of a turnout means we can go to them and say that the community really cares.”

Spina told PlanPhilly that concerns about jobs and vacancy dominated the event. Asked about why so many attendees seemed so fired up, especially about issues related to the city’s role in job creation—which isn’t strictly the purview of the Planning Commission—she said that the event is understandably seen as a place to bring concerns to the municipal government writ large.

“We try to get the message out about what this is but there is a lot of confusion,” said Spina. “We know a lot of people just think that we are from the city.”

As she acknowledged the myriad challenges attendees brought before the commission staff, district resident Larry Farmbry approached her to ask about the racial diversity of the team in charge of the West District planning process.

“I was looking at that board featuring the staff and I see only one African American,” said Farmbry, noting that the West District is vast majority black. “How do you come to a neighborhood like this and only have one African American?”

Spina acknowledged the imbalance and tried to explain the complexity of its roots, like the lack of racial diversity among planning and architecture graduates and the job’s civil service requirements. But Farmbry still seemed skeptical as he moved towards the placards detailing statistics about the area that were on display.

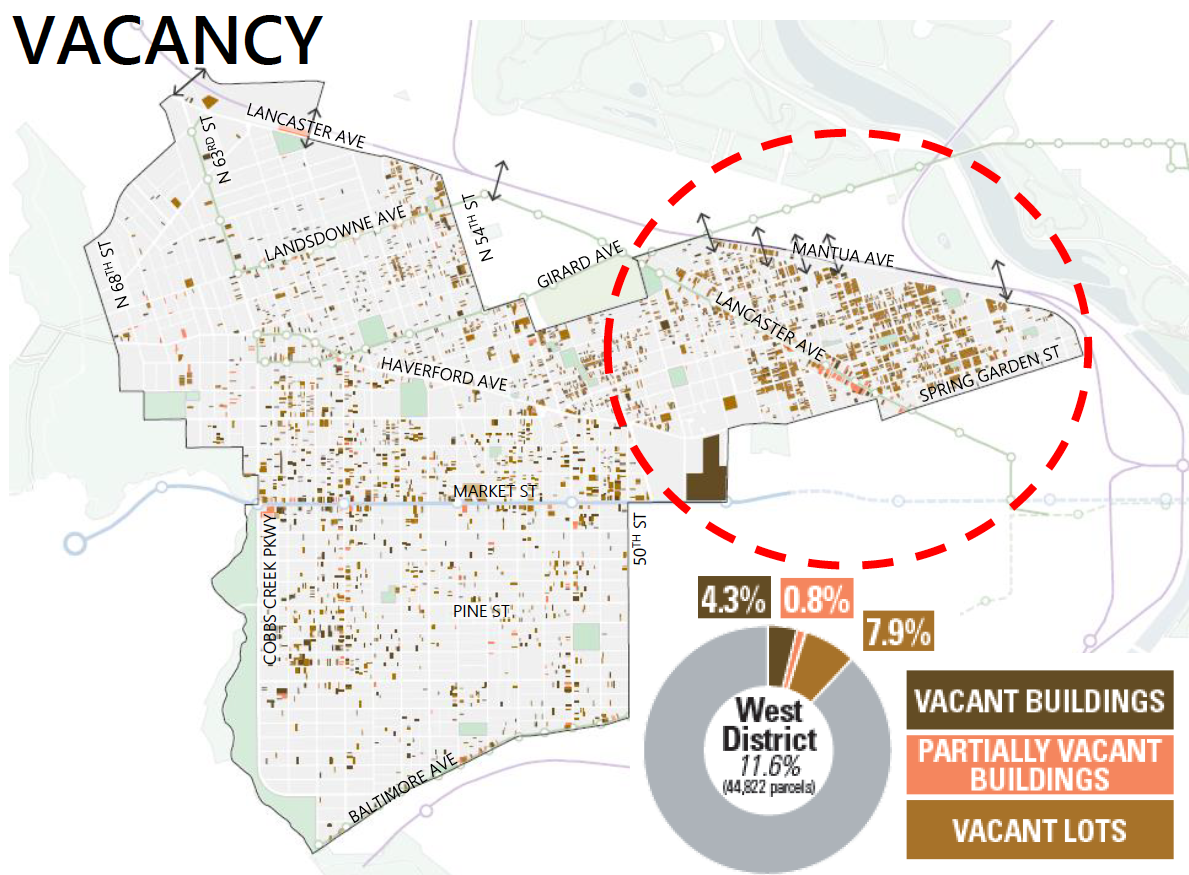

Much of the data presented to the public was extremely sobering.

In the West District 11.6 percent of the land is vacant, to some degree, with 7.9 percent comprised of empty lots, 4.3 percent unoccupied buildings, and 0.8 percent partly occupied buildings.

In some neighborhoods, especially to the north of Drexel University, the vacancy rates are staggeringly high. Mantua experiences the highest rates in the district, with 34 percent vacancy, and neighboring Belmont suffers a 33.7 percent vacancy rate. No other neighborhoods in the district even came close, but areas like Mill Creek (19.4 percent) and Haddington (11.6 percent) still experience worryingly high rates. The lowest vacancy rate is in Overbrook, with 3.3 percent.

“I had no idea it was this bad,” said Lisa Howard, who recently moved back to West Philadelphia from another state. “Even Overbrook? It’s so historic and residential, I’m surprised by that.”

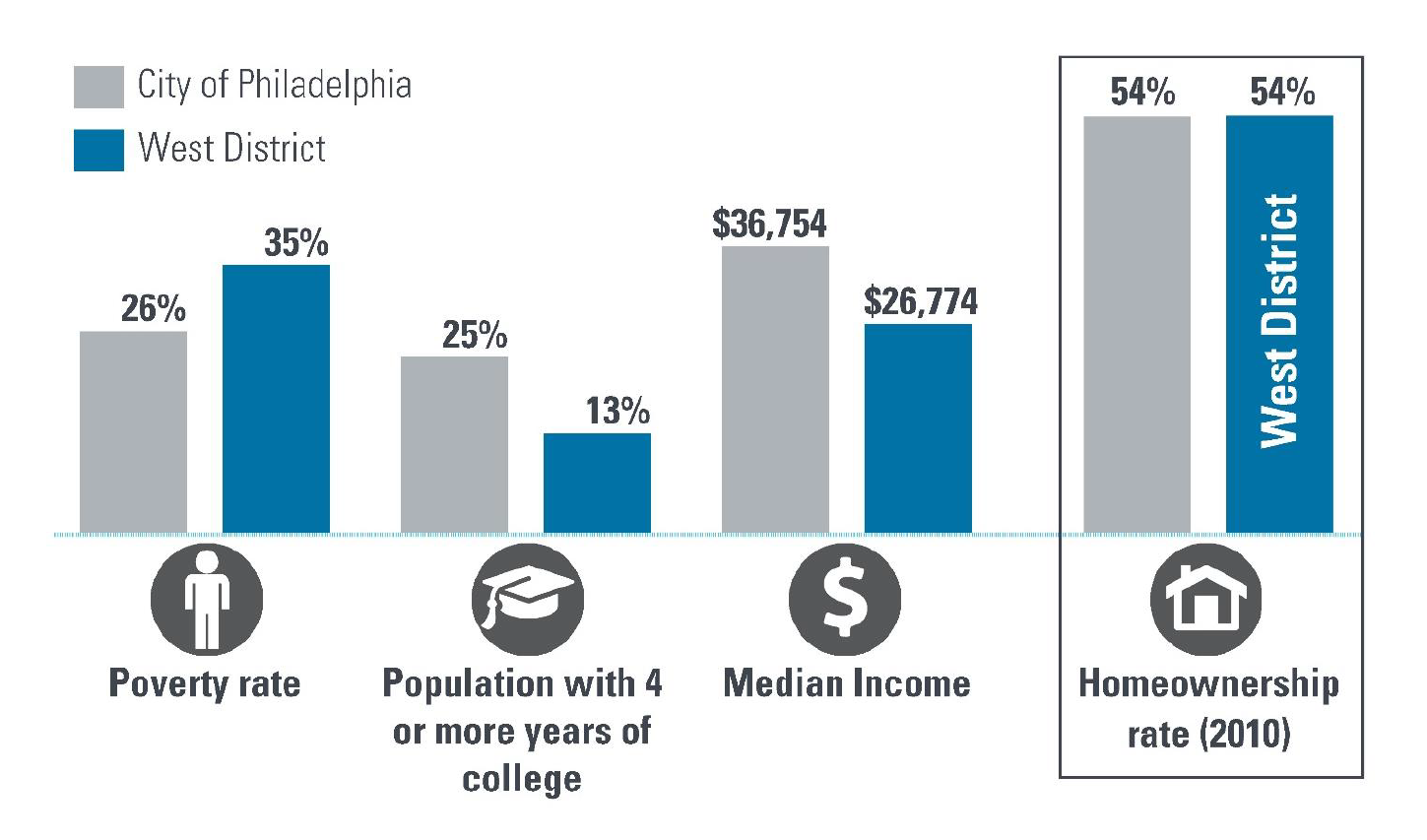

Nearly three-quarters of housing in the West District was built before 1949 and new construction remains low. Home ownership rates, meanwhile, have plunged since the turn of the new century. Between 1980 and 2000 the rate remained well above 60 percent, before plunging nearly ten points to 54 percent between 2000 and 2010—no doubt as a result of the foreclosure crisis.

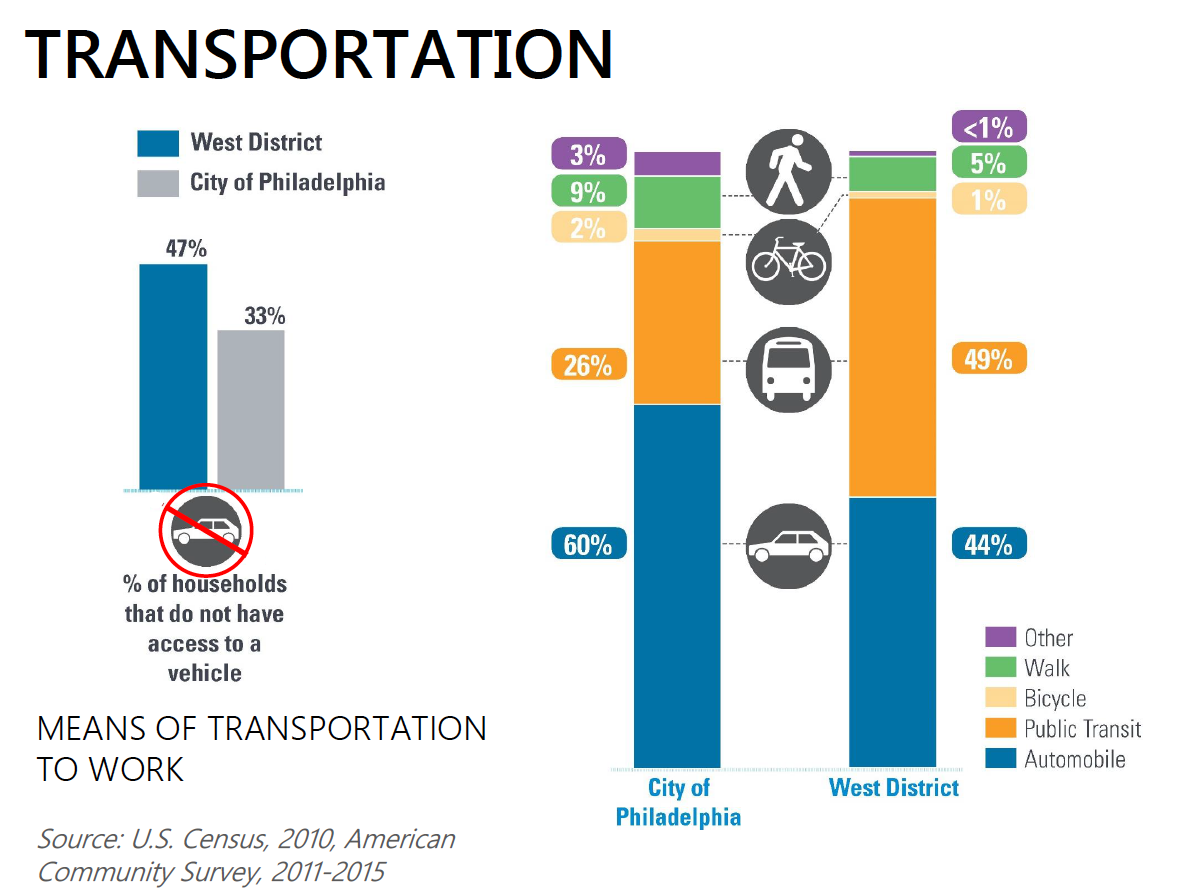

Meeting attendees generally agreed that SEPTA’s coverage of the area is one of the district’s strengths. With 12 bus routes, three trolley routes, and five Market-Frankford line stops, there are 50,000 daily SEPTA rides.

Public transit and automobiles are the dominant commuting modes, at 49 percent and 44 percent respectively. (Only 1 percent of the district’s workers walk to their jobs and 5 percent bike.) Forty-seven percent of households do not own cars, as compared to 33 percent of households in the city at large.

“Philadelphia has great transportation,” said Howard. “It may take you a while sometimes, but you can get anywhere you need to go.”

A full quarter of the area’s workforce is employed in Center City, 9 percent in University City, and 8.1 percent within the district itself. Both Montgomery and Delaware counties attract 11.8 percent of the workforce apiece, while the largest segment, 35.8 percent, go “elsewhere” for work.

Even though such a small percentage of the district’s workforce is employed in University City, the eds and meds sector employs a lion’s share of the employees: 44 percent work in “health care and social assistance” and 20 percent in education.

Thirteen percent of the district’s population has a college degree or more. The poverty rate is almost ten percent higher, at 35 percent, than that of the city overall.

For local business owner Arnett Woodall, all the placards show that sustained economic development is what’s needed. He says the city hasn’t been providing it.

Woodall’s ticks off a variety of public projects in West Philadelphia that he claims haven’t employed enough local residents. The most recent is the $50 million renovation of the Provident Mutual Life Insurance building, at 46th and Market. He said that more projects were coming, including the Rebuild initiative, and that they needed to be handled differently.

“We want jobs,” said Woodall. “The mayor promised inclusion when he ran. If he doesn’t deliver, and deliver jobs, he’s going to have a much harder time winning reelection next time. And you can tell him Arnett Woodall said so.”

The second public meeting in the West District planning process will be pushed back until September, to avoid the vacation-heavy summer months. But those who weren’t able to participate last week are invited to engage online through the end of July.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.