Ransom notes from landmark 1874 kidnapping in Germantown to be auctioned off

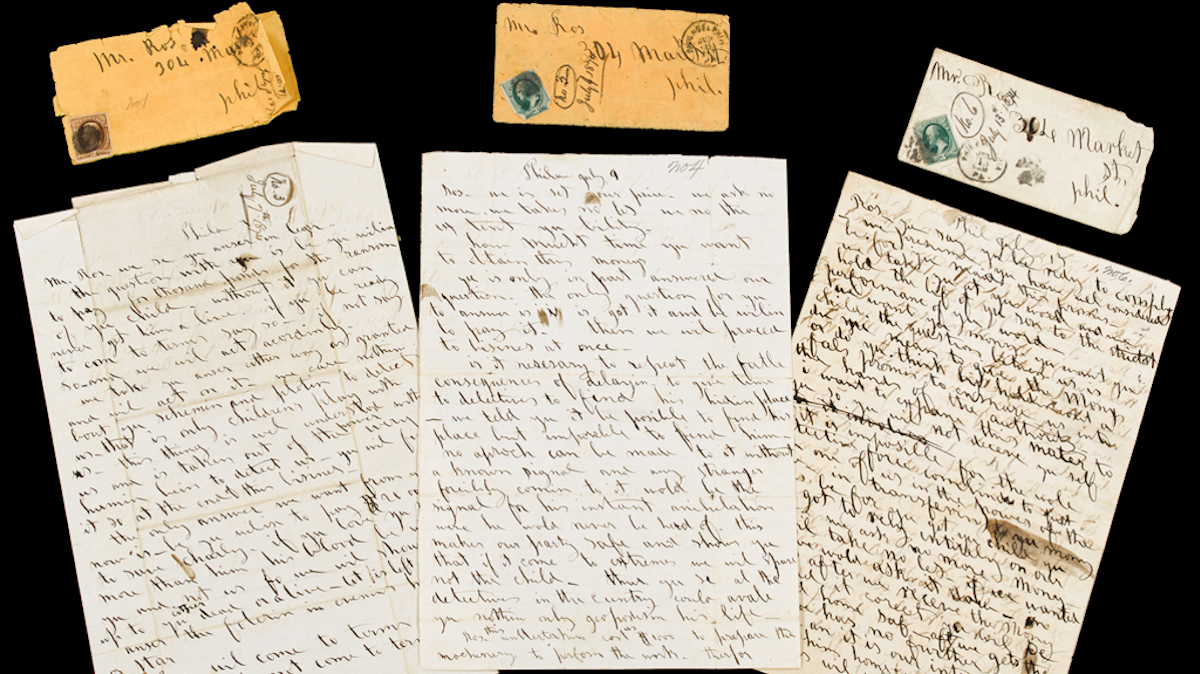

Rare finds, three of 23 ransom letters from an 1874 kidnapping that will be auctioned off on Nov. 14. (Image courtesy of Freeman's)

On July 1, 1874, two men took a little boy named Charley Ross from his father Christian’s front lawn on Washington Lane in Germantown. Three days later, a ransom letter arrived. “[B]e not uneasy,” the kidnappers wrote. “[W]e is got him.”

A second letter which arrived five days later stated their demand: $20,000.

After a five-month investigation that fueled a national manhunt and instigated more than 20 additional ransom notes, the kidnappers were killed in a botched burglary attempt.

Charley Ross never returned home.

Monumental crime

Historians identify the Ross case as the first recorded ransom kidnapping in American history.

In 1876, Christian Ross penned a memoir that included facsimiles of several of the ransom notes, but for more than a century, researchers were unable to obtain original copies of America’s first ransom kidnapping letters.

Now, they can bid on them.

An unexpected discovery

On Nov. 14, Freeman’s Auctioneers and Appraisers (1808 Chestnut St.) will auction the letters as a lot in its annual Pennsylvania Sale.

David Bloom, Freeman’s vice president and head of the Rare Books, Maps and Manuscripts department, says the sellers — residents of Northwest Philadelphia — first contacted him about a year ago.

Bridget Flynn and David Meketon of Mount Airy had “no idea” that they had America’s first ransom kidnapping letters in their basement.

Flynn’s family has lived in Germantown for generations. Her sister inherited the family documents, and after storing them in her cellar for awhile, offered Flynn their grandmother’s papers.

Knowing that her grandmother was “a good record keeper,” Flynn put the stacks of letters and old Germantown photos in her basement. She knew that a time would come when she would delve into the family’s history.

More than a year ago, Flynn and her adult daughter began sifting through the correspondence. It was then that they found the kidnappers’ ransom notes.

“When we encountered these,” said Flynn, “we were looking very specifically for something else.”

The women were searching for love letters that Flynn’s grandparents had exchanged. Flynn thought she had found them when she came across a set of old papers tied together with a black shoelace. She handed them to her daughter and asked her to read the first one aloud.

“Mom,” her daughter said, “this is a ransom note.”

Flynn and her husband then went online, typed in the name “Christian Ross” and found the facsimiles that Ross put into his 1876 memoir.

After comparing the handwriting and the contents of the letters, they realized what they had. Flynn said she doesn’t understand how her family came to possess these papers.

“I really have no idea,” she told NewsWorks.

She wonders if perhaps her grandfather, a stamp collector, purchased the letters because of the position of the stamp on the envelopes. In 1874, there was no standard stamp placement, and the kidnappers stuck theirs in the lower left-hand corners of the envelopes.

Due diligence

Bloom, who was seen various Ross memorabilia come through Freeman’s during his 30-year career, said he was initially “dubious yet hopeful” about the letters’ authenticity.

“I needed a chance to really sit with them alone for a day or so, looking to see if I could find any inconsistencies,” he said.

To review the case, Bloom ordered a copy of Christian Ross’s 1876 memoir and “We Is Got Him,” my 2011 narrative of the investigation. He then spent several hours studying the artifacts.

“I always ask, ‘What else could this possibly be?'” said Bloom.

After evaluating the paper quality and comparing the handwriting and ink smudges to those facsimiles in the books, Bloom had “a harder and harder time thinking why [the authenticity claim] wouldn’t be right.”

‘Exciting’ revelation, auction

Barbara Hogue, executive director at Historic Germantown, called the discovery “exciting and thrilling.”

The contents, she said, “tell an important story in Germantown’s history” and are “expressive, coldly calculating, and, at times, both chilling and poetic.”

Freeman’s estimates the value of the lot at $3,000 to 5,000. The contents include 23 of the original 24 letters and 20 of the original envelopes.

The auction house has also valued a period reward poster advertising details of the abduction at $100-150.

Readers can find more information about The Pennsylvania Sale, which begins at 10 a.m. on Nov. 14, at www.freemansauction.com.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.