Prison death shows system ill-equipped to handle mentally ill, East Oak Lane family says

-

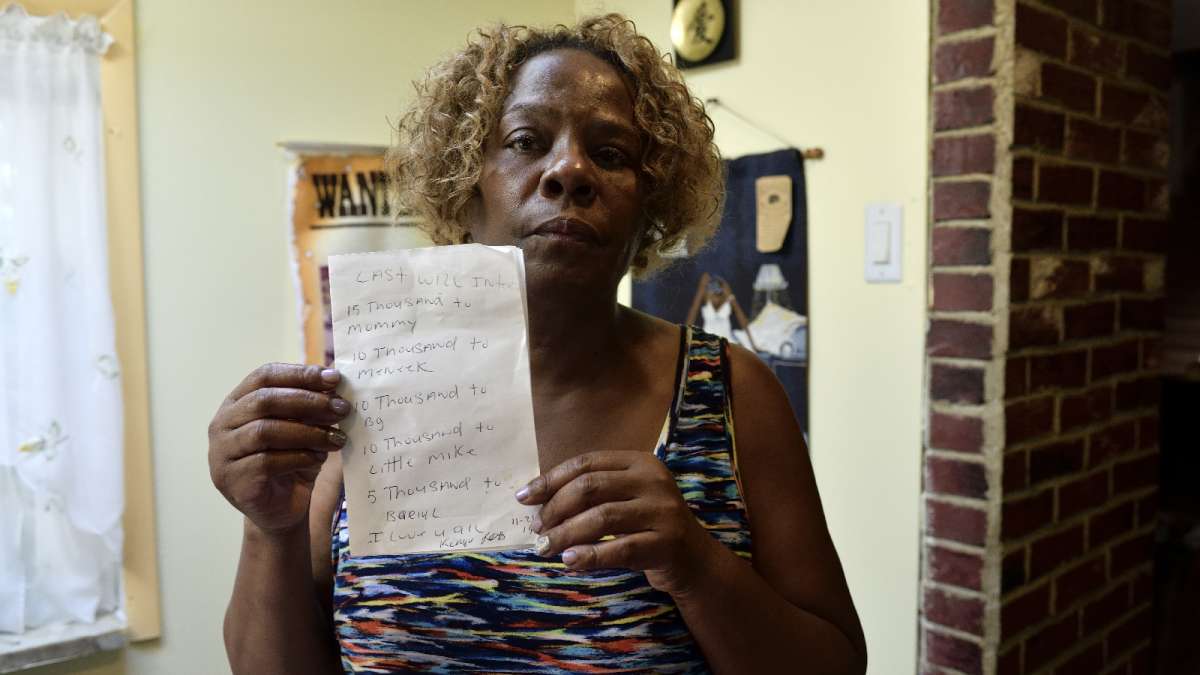

Michell Witherspoon shows a handwritten will made by her son, Kenyada Jones, in 2014. Jones died at Curran-Fromhold Correctional Facility on July 2. (Bastiaan Slabbers for NewsWorks)

-

Michelle Witherspoon with her son, Kenyada Jones. (Family photo)

-

Surrounded by medicine canisters, a photo of Kenyada Jones as a young boy lies on the dinner table at his mother's house. (Bastiaan Slabbers for NewsWorks)

-

Younger brother Meneek Jones and mother Michelle Witherspoon listen to the last voicemail recording they have of Kenyada Jones. (Bastiaan Slabbers for NewsWorks)

-

Meneek Jones shows a picture on his phone of his brother.

-

Michelle Witherspoon holds up a picture frame with photos of Kenyada Jones. (Bastiaan Slabbers for NewsWorks)

-

Michell Witherspoon holds prescription drugs belonging to her deceased son. (Bastiaan Slabbers for NewsWorks)

-

Meneek Jones expresses frustration as he talks about his search for answers in his brother's death. (Bastiaan Slabbers for NewsWorks)

-

Michelle Witherspoon recalls the last days of her son’s life. (Bastiaan Slabbers for NewsWorks)

-

Meneek Jones and Michelle Witherspoon go through a collection of framed family pictures. (Bastiaan Slabbers for NewsWorks)

Kenyada Jones was off his meds.

His mother couldn’t persuade him to come home, and mental health workers told her they wouldn’t chase a moving target. But Michelle Witherspoon knew her son was, at heart, a rules follower. So she called him and told him to go to his probation officer, where she planned to pick him up and take him for psychiatric care herself.

But Witherspoon’s plan to save her son backfired when the probation officer instead sent Jones to jail, where correctional officers found him five days later in his cell, dead of a suspected drug overdose.

As his grieving family awaits the autopsy results in Jones’ July 2 death, they can’t contain their anger at a system that treats mental illness as a crime.

And they remain tormented by questions no one will answer because, they suspect, officials regard them as potential plaintiffs. Most pressing: How did Jones get the blood-pressure medication that a forensic pathologist found at a toxic level in his system?

“My brother died because someone made a judgment call to put a person who was mentally ill — but who didn’t commit a crime — in jail,” said his brother Meneek Jones, 42, of Queens. “And he’s dead today! How can you think a jail would be better for mental illness than a hospital?”

He added: “There’s no transparency, no compassion, no common decency for people whose family died in prison. Everyone I have talked to has dismissed me like I was just going to walk away from it. That means the family, while we’re mourning, have to be investigators also.”

Shawn Hawes, a prisons spokeswoman, said she couldn’t discuss details of Jones’ death because it remains under investigation.

A system that favors prison over care?

When Jones, 45, of East Oak Lane, first began showing signs of what doctors later would diagnose as schizophrenia, they called it a “chemical imbalance of the brain.”

That was more than 20 years ago. Since then his family had become experts at not only treating his mental illness — but also foiling his plans when his confused mind plotted something that could threaten his safety.

So when Jones asked his mother for the car keys one morning in late June, she handed them over with a secretive smile, knowing her other son and daughter had removed fuses from under the steering wheel to disable the car and keep him home. Problem was, Jones’ siblings weren’t mechanics. So their well-intentioned sabotage didn’t stop the engine from starting, and Jones drove away.

It was the last time Witherspoon saw her son alive.

As she frantically made calls to corral him home, she thought of his probation officer. Jones had been in and out of criminal trouble for years, most recently for a driving-under-the-influence offense in February. She called her son and told him to go to the probation office, alerted the officer that Jones would be making an unscheduled visit, and then headed to the train station for the 20-minute ride to Center City.

But by the time she got there, he was gone, his car parked at the curb the only sign he was ever there.

“They said: ‘To be truthful, we didn’t even want him with you; he was very manic, very excitable.’ They said: ‘He kept going to the elevator (to leave), so we put him in custody.’ They said: ‘We put him in custody so he could get his medicine regulated in jail,’” Witherspoon said. “I can understand that they didn’t want him to leave. I didn’t want him to leave either. But they knew I was coming. They couldn’t put him in a locked room for 20 minutes? They couldn’t take him to the hospital?”

Meneek Jones added: “He wasn’t being aggressive. He was sick. He didn’t break any laws or violate probation. He just needed help managing his medication. He needed to go to a mental health place where people know how to handle people with his problem.”

Marty O’Rourke, a spokesman for the First Judicial District, acknowledged that the committing paperwork noted no crime nor probation violation.

“A determination was made that based on his erratic behavior, he posed an imminent danger to himself as well as other people, and based on that determination, he was detained,” O’Rourke said.

O’Rourke couldn’t explain why officers opted for prison instead of a psychiatric placement.

But Angus Love bets he can.

“It is extremely easy to take somebody to prison, and it is extremely hard to take them to a mental institution, in terms of paperwork, hearings, that sort of thing,” said Love, executive director of the Pennsylvania Institutional Law Project. “It’s just the way the system is set up – it favors prison.”

In fact, 42 percent of the city’s 7,330 inmates have some sort of mental illness, with 33 percent considered “seriously mentally ill,” Hawes said.

Jones’ story might have ended there, as just another man taken to prison in a city so quick to incarcerate that lawyers have repeatedly sued for prison crowding and a $3.5 million effort is underway to cut the city’s bloated prison population.

But five days after he went into Curran-Fromhold Correctional Facility, he died in his cell.

A family hunts for clues in the absence of answers

Deaths in prison aren’t unusual — inmates’ poor habits, addictions or lack of health care in the community make them a medically vulnerable population. Jones was one of seven inmates to die in city prisons so far this year, down from 19 in 2015.

But Jones’ family never expected he would die in prison. Had he perished at the hands of police, that would have been less surprising, Meneek Jones said, with so many high-profile cases nationally of police shooting mentally ill people to death.

Jones behaved oddly often enough that his family endured a constant undercurrent of stress over how his mental illness might land him in trouble.

“What scares me the most is that people don’t understand mental illness,” Meneek Jones said. “If he doesn’t take his medication the right way, he doesn’t act right. But he doesn’t need to be manhandled. He needs medical care.”

The last time Witherspoon talked to her son, he called from prison to tell her he didn’t feel well. He’d thrown up his meal, and his belly was burning, he told her. He was hyper and confused, convinced he’d been in jail 14 days when it’d been just four days. “Call somebody,” he begged her.

Witherspoon called the probation officer who had sent her son to jail.

“I told her: ‘I don’t want you to kill my son. Get him help,’” Witherspoon said.

“The next day, I’m driving — I went to Burlington Coat Factory to do some shopping — and I get this phone call, and this chaplain from the prison says, ‘Is this Michelle Witherspoon? I’m sorry to inform you that your son passed away,’” Witherspoon recalled. “I said: ‘What are you talking about?!’ I thought I was hallucinating.”

The chaplain and other prison officials gave Jones’ family no details.

But as they began investigating, they learned from police that correctional officers found him collapsed with packets of pills in his cell, and that toxicology tests showed Jones had 289 milligrams per milliliter — nearly 30 times the recommended maximum daily dose — of Amlodipine, a blood-pressure medication, in his body.

Still, Jones’ cause and manner of death remain “pending,” because the Medical Examiner hasn’t yet ruled in the case, spokesman Jeff Moran said.

The family doesn’t know if medical professionals in the prison administered a fatal dose of medication, or if Jones was given a “keep on person” supply of medication and overdosed.

“We don’t know anything,” Meneek Jones said. “We haven’t really been able to find out how things work in the prison system.”

Many prisons allow low-risk inmates to self-administer some medications. In Philadelphia, the “Keep on Person,” or KOP, policy permits medical staff to give inmates without a history of self-harming behavior or addiction a 30-day supply of medication, excluding narcotics and psychotropic, HIV, seizure and such drugs.

If Jones was given medication to self-administer, his brother said, “that would be a problem because he wasn’t of sound mind. He didn’t know what was going on; he wouldn’t know what dosage was correct or incorrect.”

New inmates typically spend their first five days in quarantine, as medical staff screens them and sorts out their various needs. Quarantined inmates also generally wouldn’t be given medication to self-administer, Hawes said. It was unclear whether Jones was still in quarantine when he died on his fifth day behind bars.

Corizon, the Tennessee-based, for-profit private firm that provides healthcare to the city’s inmates, has endured criticism — and lawsuits — for alleged deficiencies in its corrections care, both in Philadelphia and elsewhere. Philly officials contracted with Corizon four years ago, at $42 million annually, to provide prison healthcare, Hawes said. Virginia-based MHM Services, Inc., which provides mental health services in city prisons, has a $13 million annual contract, Hawes added.

As the Jones family continues hunting for answers, one thing remains clear.

“A lot of people who go to prison may not have family that cares, and so it’s just swept under the rug,” Witherspoon said.

“But they messed with the wrong person here. We loved Kenyada. They’re not going to get away with killing my son.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.