Princeton’s comic book exhibit spotlights superheroes of civil rights movement

From Rosa Parks to Martin Luther King Jr. to U.S. Rep. John Lewis, comics illustrate the fight for equality.

Listen 4:49

"Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story," a comic book written in 1958, tells the story of the Montgomery bus boycott and provides instruction on nonviolent resistance. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

“Not all superheros wear capes” is a common refrain these days.

That message was especially true during the civil rights movement, when ordinary citizens fought for basic dignities.

An exhibit at Princeton University focuses on a little-known tool activists used during those days: comics. Comic panels telling the story of civil rights milestones cover the 200 feet of wall space in the Bernstein Gallery at Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

They’re excerpts from two comics — a 1958 comic book and a graphic novel trilogy published in 2013 to 2016. Both chronicle nonviolent protests that were met with brutality and intimidation.

“Martin Luther King Jr. and the Montgomery Story” covers Rosa Parks momentous refusal to cede her bus seat to a white man and the ensuing bus boycott in 1955 led by Martin Luther King Jr.

While comic books might be considered frivolous, the Montgomery comic served as a tool to teach nonviolent resistance, according to the Rev. James Lawson of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the group that published the comic.

After three years in India studying Gandhi’s nonviolent movement, Lawson introduced the concept of peaceful resistance to many civil rights activists. With the help of the comic, he trained thousands through his workshops, preparing them for lunch counter sit-ins and the freedom rides.

“I used that in my travels around the South,” he said. “In my teaching, I passed out hundreds of them, to the Little Rock Nine, people in Nashville, in Huntsville and wherever I went.”

In 1958, the term nonviolence was largely unheard of, said the United Methodist minister.

“Remember we did not have much literature on nonviolence at that time,” Lawson said. “So developing a story about nonviolence was part of the creative work that I myself did and others like me did at that time. So it was but one tool, but it was a good and important tool.”

Sy Barry, a cartoonist for the precursors to the DC and Marvel studios, illustrated the Montgomery comic as a congressional subcommittee tried to link comics with juvenile delinquency.

“It was a sin to have a comic book around or have a newspaper with comics in it. Kids in the back would be reading the comic strip in the back of the textbooks,” the Long Island, New York, native said. “You couldn’t even read the Daily News because they knew that it had comics … So that was the attitude towards comics. It was looked on with great disdain by teachers.”

Known for his work on Flash Gordon and, eventually, The Phantom, Barry said he wasn’t sure how the Montgomery comic would be received.

“I knew it would be held with some disregard down in the South, and there would be resistance to it probably,” he said.

With its mass appeal and ability to reach readers of many levels, however, the format was a success.

“Their goal was to make a work that would appeal to and educate both the adults and the children in the South and in the North. Both audiences were critical for propelling the civil rights movement,” said Mary Oestereicher Hamill, co-director of the Bernstein Gallery.

Also part of the exhibit is a graphic novel series written by and about U.S. Rep. John Lewis of Georgia. It chronicles the 1965 march he led across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, on a day known as Bloody Sunday because of the violent beatings demonstrators suffered at the hands of state troopers.

The illustrations in “March” don’t downplay the violence, said Hamill.

“As with superheroes in comic books, the violence of those who hated the black people is powerfully conveyed,” she said.

Hamill says the exhibit, open until Nov. 15, was scheduled during election season on purpose.

“The principle of ‘one man, one vote’ is extraordinarily important,” she said. “As students walk through this gallery, it’s appropriate for them to be reminded that they need to vote. People have lost their lives over this issue, and it’s a right not to be wasted.”

The Princeton exhibit took two years to put together and is directly derived from the 2016 exhibit, “From MLK to March: Civil Rights in Comics,” at the August Wilson Center for African American Culture. The original show was curated by art historian Sylvia Rhor, funded by the Pittsburgh Foundation and organized by Rob Rogers, past president of the now-closed ToonSeum: Pittsburgh Museum of Comics and Cartoon Art.

The comic books’ intersection

Rev. Lawson trained John Lewis when he was a teen, giving him the Montgomery comic. Lewis has said it had a profound effect on him.

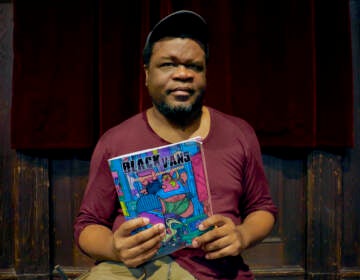

Andrew Aydin, who created and co-wrote “March,” serves as the congressman’s digital director and policy adviser. He said the work was born as Lewis reflected on Barack Obama’s election as president.

“It was a very real question in John Lewis’ world … how do you teach young people about the civil rights movement and how do you explain to them what John Lewis’ contribution was,” he said.

Lewis also wanted to address the lack of civil rights education in the United States, an oversight the Southern Poverty Law Center has called “deplorable.”

Most U.S. students graduate from high school knowing only nine words about the civil rights movement: Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King and “I Have A Dream,” a center study found in 2014.

Aydin, a comic book aficionado, suggested that format, hoping it might influence a new generation to become civically engaged — much the way the Montgomery comic did.

“I just started saying, I think there should be a John Lewis comic book, and everybody thought I was nuts,” Aydin said.

“March” won the National Book Award, American Library Association awards and many other honors. Aydin and Lewis are currently working on a sequel, “Run.”

The Montgomery comic illustrating nonviolent demonstrations continues to make its way around the world. It helped shape anti-apartheid sentiment in South Africa, as well as inspire nonviolent demonstrations in Latin America, Vietnam and Egypt.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.