Princeton exhibit explores Jewish roots in Antebellum America

We tend to think of the first Jews coming to America in the late 1800s, forced out of Eastern Europe by the pograms, but Jews began emigrating to the Americas much earlier, seeking religious freedom and economic opportunity. The first Jews settled permanently in New Amsterdam in 1654. By the time of the Civil War, it is estimated there were 150,000 Jews living in America.

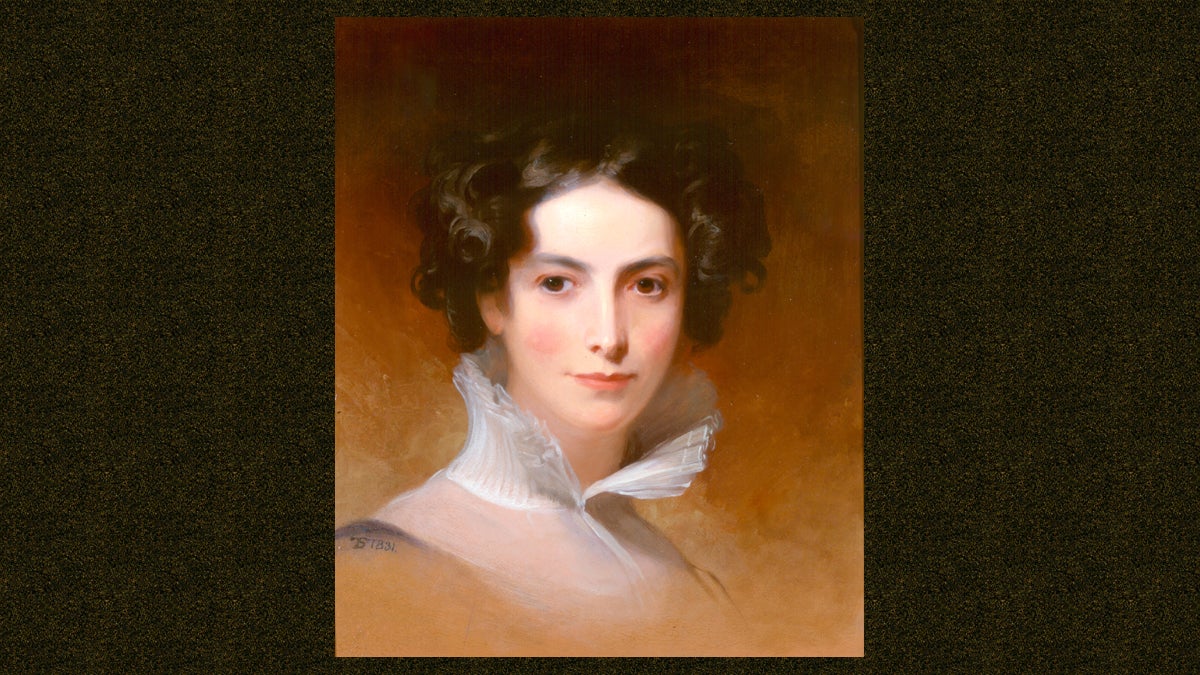

The first Jewish settlements in the New World were 17th-century offshoots of the diaspora of Sephardic Jews, who traced their origins to Portugal and Spain, according to a Princeton University Library exhibition at the Princeton University Art Museum. By Dawn’s Early Light: Jewish Contributions to American Culture from the Nation’s Founding to the Civil War, on view Feb. 13-June 12, explores how, in the earliest days of the United States, Jews began to grapple with what it meant to be Jewish and American.

Jews adopted and adapted American cultural idioms to express themselves in new ways, inventing American Jewish culture. The exhibit showcases Jewish voices through more than 150 early novels, poems, plays, newspapers, photographs, scientific treatises, religious works and paintings produced by Jews in the United States. These works illuminate the creativity of Jews in the new Republic, as well as the birth of American Jewish culture.

“Living in an age when Jews are fully integrated into so much of America’s public and popular culture, it is difficult to imagine a time before they shone on the stage, screen, and printed page,” says Curator Adam D. Mendelsohn in his catalog essay. Mendelsohn is Director of the Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies and Research at the University of Cape Town, South Africa, and author of “The Rag Race: How Jews Sewed Their Way to Success in America and the British Empire.”

The materials for Dawn’s Early Light come largely from the Princeton University Library’s Leonard L. Milberg ’53 Jewish American Writers Collection. Among the writers in the Milberg collection, books by whom he began donating to the Princeton University Library in 1999, are Woody Allen, Hannah Arendt, Paul Auster, Saul Bellow, E.L. Doctorow, Jonathan Safran Foer, Allen Ginsburg, Joseph Heller, Lillian Hellman, Norman Mailer, Arthur Miller, Dorothy Parker, Gary Schteyngart, Art Spiegelman, Wendy Wasserstein, C.K. Williams and many others.

“I hope to demonstrate that America’s extraordinary and unique freedom of religion,speech and movement, and also being a country offering economic opportunity and political participation to all, created an atmosphere which enabled Jews to thrive and consequently be able to contribute to America’s cultural Life,” Milberg writes in the introduction to the exhibition catalog.

The Jews earliest to arrive in the New World settled in the Caribbean islands and South America. “Most of the newcomers were from German-speaking lands, but also from Russia, France and England,” says Mendelsohn, a South Africa native. In distant outposts of British and Dutch empires, Jews could find more freedom than in Europe. Men and women could dream of prosperity, moving freely among port cities. Fashions, books, newspapers, ritual objects, kosher meat and ideas traveled with them.

By the 1840s, after hurricanes, tsunamis and earthquakes leveled cities and their synagogues, Jews began migrating to North America.

“As individuals, [Jews] were free to participate as full citizens in the hurly-burly of the new nation’s political and social life,” writes Mendelsohn. Although they were few in number, Jews in Colonial American attracted attention. The concept of the Promised Land in the Old Testament seemed like America itself.

With the Jews came music. American Jews were composers and performers of classical music and opera. Henry Russell, who began life as Henry Levy, studied opera as a teenager in Italy before touring as America’s most popular balladeer. As the musical tastes of Jews evolved, Reform Judaism got its start when a Charleston synagogue installed an organ to accompany religious worship.

In order for Jewish identity to continue in this culture, pedagogical materials were developed to teach the Hebrew language and Jewish history. American Jews had little tradition of writing fiction and secular poetry at the dawn of the 19th century, even less so for women. Over the next five decades, authors began to experiment with genres and styles and the Jewish reading public expanded. Some of the new writing was for and by women. With new pressures on Jewish life, female writers could help female readers understand the world in which they were living. Male editors and publishers were interested in this poetry and prose that would entertain and edify American Jews, leading to an American Jewish literary revolution.

“The two fields in which early American Jews were in the forefront were theater and publishing,” writes Milberg. “Jews were active in every aspect of the theater, from opposing Protestant moral objections, building new theaters, acting, playwriting, criticism and patronage.”

Jews participated in the political dialogue in this country as early as the 1700s. They vocalized their views in public but often turned to print. Jews played a prominent role in newspaper publishing, writing and edited works of general interest. But as the Jewish population grew dramatically and the steam-powered press made mass printing cheaper, publications related to Judaism and Jewish culture increased in number. And as Jews began turning away from the synagogue, some religious leaders used the Jewish press as a way to reach them.

It became a continuing struggle for religious leaders to keep Jews in the synagogue as they began affiliating with non-Jews. Even as Jewish immigrants began to arrive in increasing numbers, they were less inclined to be religious and were marrying outside of their faith in significant numbers. As Reform Judaism grew, services and prayer books were offered in English.

In 1818, Thomas Jefferson wrote that American Jews should pursue education as the most powerful antidote against prejudice. Areas of medicine and science opened to ambitious and inquisitive Jewish men and they achieved renown in areas of innovation.

America was never perfect, says Milberg; one of the last of his purchases was an 1850 anti Semitic Mother Goose. But, he adds, anti-Semitism did not prevent Jews from achieving success in media, theater, law and the judicial system, prison reform and founding universities and museums.

_______________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.