Preservation awards honor major tax credit projects

Adaptive reuse of large-scale historic properties will be spotlighted when the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia presents its annual achievement awards on May 15. Three of the projects also took great advantage of the federal preservation tax credit program to make their restoration possible.

Historic neighborhood

The transformation of the Lafayette Building, 5th and Chestnut Streets, into the Kimpton Hotel Monaco was “a great introduction of new life to the Washington Square neighborhood,” explained Patrick Hauck, director of the Neighborhood Preservation Program at the Preservation Alliance. “The interior has been changed, but the exterior is beautifully restored. This is a great example of how a historic building can be reused to enliven an important public space.”

The 11-story Lafayette, named for the preservation-minded Revolutionary War hero General Marquis de Lafayette, was one of the few office buildings in the Independence Mall area when it went up in 1907. Plans to convert the building into condominiums fell through, and the Lafayette sat vacant for several years before the Kimpton company considered the property.

Jack Paruta, of Gensler Architects, led the Hotel Monaco project.

“This was a pivotal project for our client,” Paruta said, “and it was such a key location. Kimpton had previously renovated the Architects Building [at 17th and Sansom] into the Palomar, and they were open to the idea of another property in Philly. Two hotels are better than one for them, and the market was right for this project. The location was more than optimal, with its proximity to the historic district,” Paruta said. “Kimpton liked the historical significance of the building and the chance to improve its presence in Philadelphia.”

There were a variety of challenges at the Lafayette, including the condition of the building after three years sitting fallow. “It had been very neglected. The interior and exterior were in fairly poor condition, so making the assessment was very key,” Paruta said.

Applying for federal tax credits provided financial benefits, but also raised challenges. “The downside is some of the limitations to what you can do to the building,” he continued. “We had to be very sensitive in everything we did. We had to follow the federal standards for rehabilitation, and we were under the jurisdiction of the Philadelphia Historical Commission” because of the building’s historic designation.

Gensler had to pay attention to any material that was removed, what historic fabric had to remain and be preserved, any details that were replaced or altered, color schemes, entrances, signage, storefronts, and “anything with regards to putting things on the roof,” Paruta said.

The electrical and plumbing systems had been previously removed from the building, so major equipment had to be installed on the roof. “The sightlines had to be considered throughout the project because it is in such a prominent location. The equipment on the roof couldn’t be too conspicuous or dominate the appearance of the building,” Paruta said. “We also put a rooftop bar on top and a large outdoor terrace. Instead of building up, we removed a portion of the roof and almost built down to keep the presence of this thing as inconspicuous as possible.”

An unexpected challenge arose on the street level as well. The sidewalks surrounding the building sat over the basement. And the structure below the sidewalk, “unbeknownst to us, had deteriorated past the point of being able to save it,” Paruta said. Gensler had to replace the old structure with new steel and decking and new concrete sidewalks.

The entire project took two years, “from due diligence to opening,” he said.

The cost: $50 million.

But the historic tax credits totaled about $10 million. “That made the project financially feasible. With a project of this size, without credits, maybe it doesn’t happen,” Paruta said.

The hotel also received LEED Gold rating, though “the rating system, we found, plays no favorites for doing historic building renovations. The constraints don’t lend themselves to the fact that we’re reusing an existing building. We were very ambitious with efforts to reduce water and power usage and many other aspects with regard to LEED rating. Adaptive reuse is a very sustainable practice, but it doesn’t translate so much in the LEED rating system – at least not yet,” Paruta said.

In any case, there were no regrets.

“The building was dying, and Kimpton was very ambitious in its development goals. It was looking for this kind of historic building stock. This kind of project is a win-win for them, and for the cities where these buildings reside.”

A commercial corner

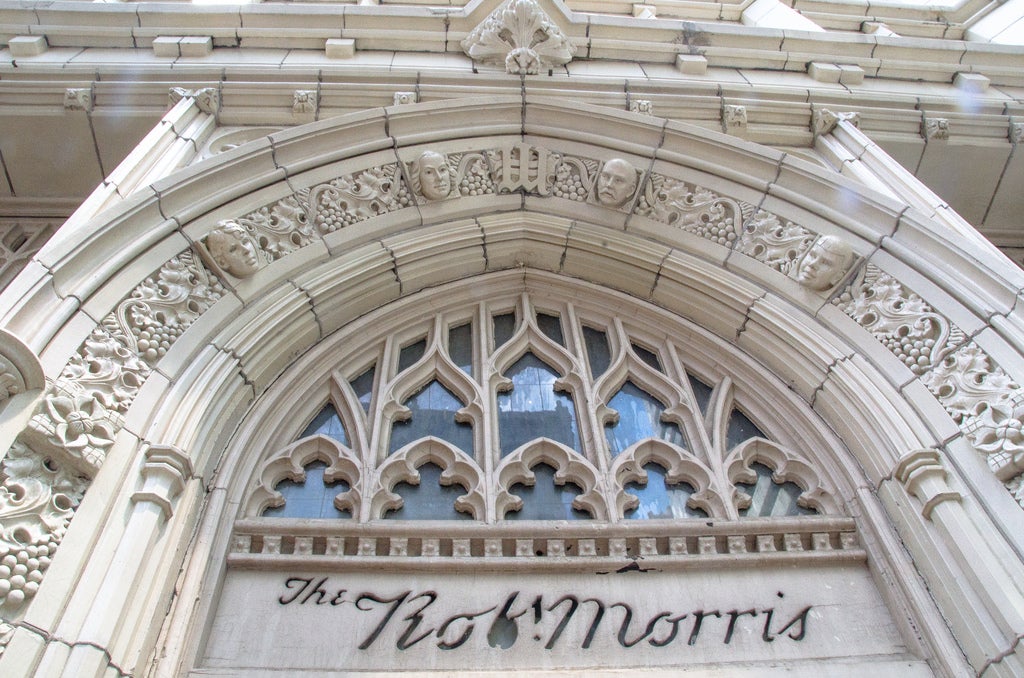

A building in another important neighborhood – and named after another Revolutionary War figure — will also be cited this week by the Preservation Alliance. The Robert Morris Building, at 17th and Arch Streets, whose neighbors are mainly new office towers like the Comcast Center, is another “great example of adaptive reuse,” Hauck said.

In addition to returning the beautiful entrances to their original condition and restoring the elaborate terra-cotta work that covers the facades, “this was a complex building that made it a complicated project to take on technically,” Hauck said. “It is a great example of a low-rise building of its day that has been given new life.”

Originally named the Wesley Building, it was erected in phases in 1914-15 and 1921-22 by the firm of Ballinger & Perrot (later the Ballinger Company). The top eight floors were added six years after construction of the first six. The architects chose the Gothic style for the early skyscraper, which contained offices as well as the Robert Morris Hotel, owned by the Methodist church.

The building was purchased in 2007 by 806 Capital, which considered turning the Robert Morris into student housing or a hotel. In 2012, 806 Capital and Federal Capital Partners decided to convert it into a complex of 111 apartments called The Arch.

Leo Addimando, of 806 Capital, said there were many challenges in restoring what he described as “a C office building in an A location.”

Among the toughest issues was the restoration of the second-floor ballroom in a way that met historic preservation guidelines. “The ballroom used upset beams, which is a fancy way of saying the structural support was on the third floor for a second-floor space,” Addimando said. “Above the ballroom we built three apartments, and we had to be very creative in running the utility systems. We also had [Americans with Disabilities Act] issues; we put a ramp in to get people up to those three apartments. We had elevator issues, too, because we couldn’t increase the shaft size. We had to use every centimeter to make them ADA-compliant.”

On the north and west sides, the building’s old steel windows were made operable and energy efficient. To the south and west, the original wood windows were replaced in similar style.

“We also had structurally compromised sidewalks. So we replaced the steel structure for safety and for water infiltration reasons,” Addimando said.

Another big challenge was the terra-cotta decoration that gives the building its distinctive appearance. The project had to follow state and federal preservation standards, in addition to guidelines from the Historical Commission and Preservation Alliance. “How we dealt with certain architectural details were heavily dissected” and required careful negotiations, Addimando said.

Cost for the terra-cotta restoration alone was $2 million. Total “hard cost” for the 12-month restoration, Addimando said, was $23 million. The Arch project received $7 million in federal preservation tax credits.

“We’ve done a lot of historic renovation,” he said. “This project was gratifying because the building had not been touched for over 30 years. This is a very important corner in Philadelphia, and it had become an eyesore on that block.” By bringing in new retail tenants and residential tenants, “we’ve really activated that corner and the streetscape.”

An overlooked area

The third major project to be honored by the Preservation Alliance is the Pennsylvania State Office Building at 1400 Spring Garden St. “This is one of the first Mid-Century Modern projects to be done with historic tax credits,” Hauck said. “It might have gotten remodeled anyway, but it might have lost some of the character. It’s exciting to see some of these Mid-Century buildings become rehab tax credit projects.”

Added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2010, the State Office Building went up in 1957-58. According to its nomination to the National Register, it was designed by some of “the brightest stars of the period,” the architectural firms of Caroll, Grisdale & Van Alen; Harbeson, Hough, Livingston & Larson; and Nolen & Swinburne. The landscape design was by the internationally renowned landscape architect Ian McHarg. They created an 18-story, steel-frame and reinforced concrete structure, covered in white marble exterior panels. The building contained 400 offices for 2,000 state employees.

The state sold the building in 2008 to Bart Blatstein’s Tower Investments for $25 million. Blatstein said the building had been vacant for a year before his company took ownership.

This was Tower’s first work on a historic property, Blatstein said. “This was an undervalued, overlooked section of the city” that needed rehabilitation, he said.

“The building had been neglected for many years. There was water seepage into the basement from the platforms above. The whole project involved a general tightening up of the building,” he said.

He declined to reveal the overall cost of the project, or the federal tax credits he received for the work. Philly.com reported in January that the new 204-unit apartment building, called Tower Place, was a $70 million renovation that received under $10 million in historic tax credits.

The grand jury award from the Preservation Alliance for his first historic building was a “great honor,” Blatstein said. “It’s nice to be recognized for our work on this very cool building. People are passionate about this building. Some don’t like it. But it definitely evokes some kind of feeling.”

For the full list of Preservation Award winners and the May 15 ceremony, go to www.preservationalliance.com.

All photos courtesy of the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.