Philly’s Civic Engagement Academy expanding to meet booming demand

Since late November, the city’s Office of Civic Engagement and Volunteer Service has received at least one request per day from people interested in volunteer opportunities—a rate that far surpasses the number of opportunities the Office has available.

“The political environment is now reminding people that they need to give back to their community and engage with neighbors,” said Chief Service Officer Stephanie Monahon. “Everyone is hearing people say, ‘I want to know how to be more engaged in my government, my community,’ so how do we open those doors?”

Amanda Finch, Deputy Service Officer for Civic Engagement in the Office of Civic Engagement and Volunteer Service, said she even received an email from a person who had quit a job to do volunteer work around the country and wanted to know how to help in Philadelphia.

“People want to feel like they’re making a difference,” Finch said. “They want to do something to combat what they’re seeing in the media and respond to the change from an administration on the federal level who really cared about individuals to what we have now.”

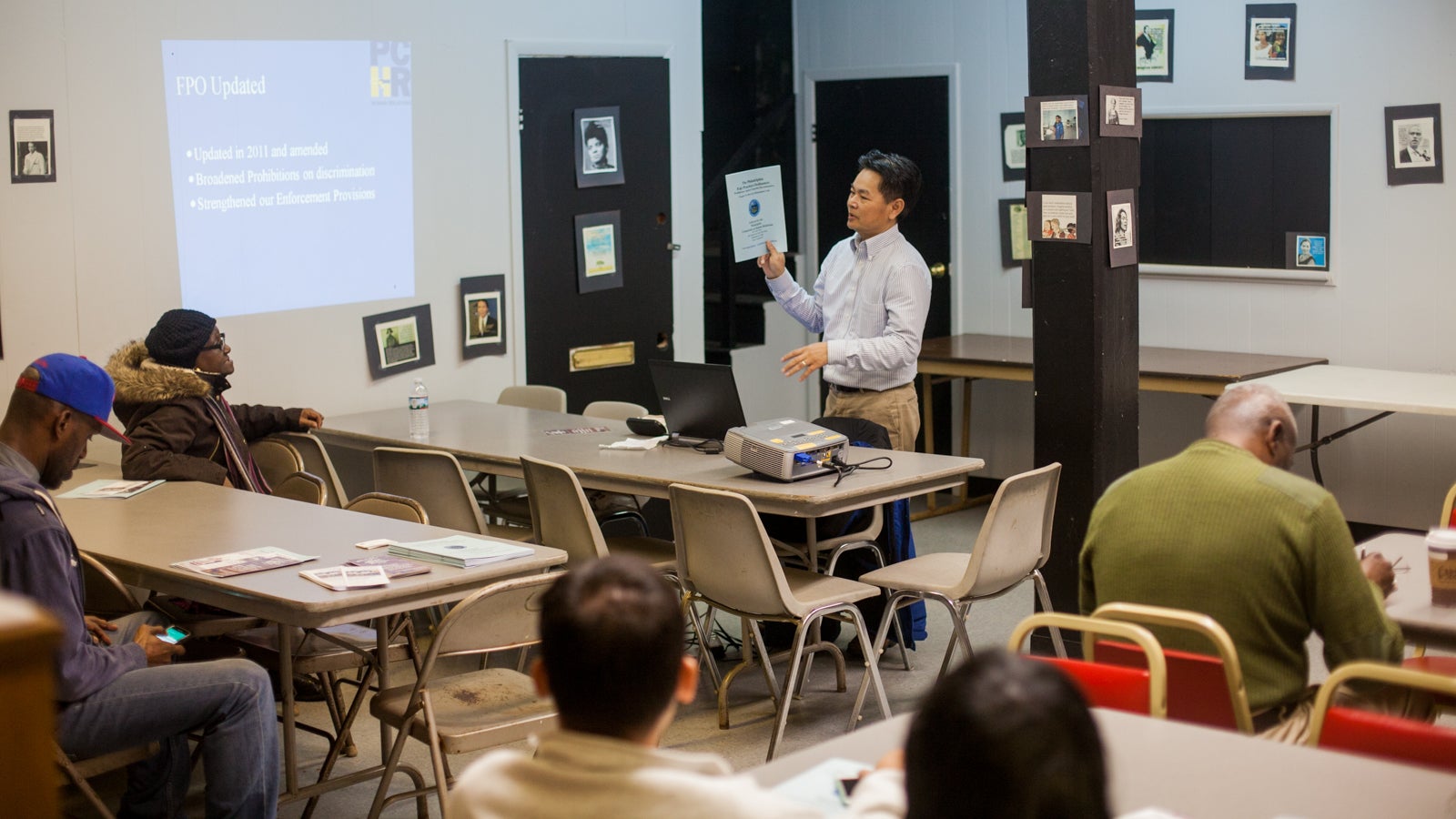

In response to a new outpouring of interest, the office started ramping up civic engagement offerings. It began by publicizing a little-known program it has been running since 2010: the Civic Engagement Academy (CEA). The CEA brings representatives from different city departments—including Licenses and Inspections, the District Attorney’s office, the Managing Director’s Office, and the Streets Department—to community centers, schools, and churches in underserved neighborhoods in an eight-week long course that meets once a week. The program is designed to introduce residents to various city departments, provide information about how to effectively access their services, and encourage residents to share the information with their networks. CEA works with community organizers upon request, and the office of civic engagement tries to tailor CEA sessions to the particular interests and needs of the community.

To publicize the CEA program to more Philadelphians, Mayor Kenney sent a citywide email on February 13 encouraging people to sign up. In the first week, 576 people signed up for the CEA—almost double the number of people who graduated from CEAs between 2010 and 2016. “It’s more interest than we ever thought,” Finch said.

To meet this need, the Office of Civic Engagement is planning 10 CEAs in various neighborhoods in 2017. Upcoming spring courses are scheduled in Upper North Philadelphia, Frankford, and Elmwood. And this Saturday (March 18) the city is hosting the CEA in a Day, which will take place in at the Municipal Services Building from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. for up to 300 participants. The Office has been collaborating with the Committee of Seventy and Young Involved Philadelphia to expand outreach and to incorporate “Government 101” (a crash course on government structure) and information about elections into the CEA in a Day. There have also been efforts to make the CEA more interactive than it’s been, with assignments and activities for participants.

Dan Gabor, a professional organizer around workers’ rights and LGBTQ nondiscrimination, is one of the people who signed up for a CEA in April after reading the citywide email. “Even as someone who’s been involved in government and around appointed leaders, there’s still so much more to learn,” Gabor said. “My familiarity with city government is only in a few specific areas. It’s a daunting task to figure out how to navigate.”

Gabor’s said he’s interested in learning how to better use the tools and services the city provides to advance the causes he cares about—both personally and professionally—including gaining back local control of the public education system, reforming the criminal justice system, and protecting the environment. He also wants to know more about the issues in Port Richmond, where he’s lived for a year, by becoming a more involved neighbor.

The Civic Engagement Academy aims to demystify how city services work and how to take advantage of what’s available. For example, the Community Life Improvement Programs (CLIP) removes graffiti that the public reports and allows tools to be checked out and used for community cleanups. The Office of Immigrant Affairs might warn an immigrant-heavy community about Notario fraud and go over people’s rights. Most CEAs also address questions about how to use the city’s 311 system, what happens with trash pickup on holidays, how to get a recycling bin, how to tell the difference between (and respond to) litter and illegal dumping, and how to deal with vacant properties. Some presenters attempt to ameliorate frustration by explaining processes behind bureaucracy, such as why it takes 90 days for a vacant lot to be cleaned up.

The classes also encourage block-level engagement, such as checking in on neighbors during heat waves, and offer concrete ways for residents to be involved: becoming a block captain, joining a friends group of a park, or sitting on an rec center advisory council. Daniel Ramos, Philly311’s Community Engagement Coordinator, said that after the Philly311 session course of the CEA, about 75 percent of participants go on to complete additional training to become neighborhood liaisons, volunteers who record concerns voiced during community meetings and report them to 311.

Residents in Grays Ferry have just finished their CEA and are interested in tapping into more resources and communicating directly with representatives from the government.

“I’m here to learn more and give information back to my community,” said Charles Reeves, President of the Resident Action Committee of Grays Ferry, who attended each course in their CEA. “Our community needs a lot of help. We’ve got a lot of violence, schools failing.”

For resident Ralanda King it’s about finding new access to resources her neighbors need “This area is always going underserved, and we’ve been trying to find out ways to be relevant in all these trying times of changes,” she said, giving a side-eye. “What I need is some empathy and understanding to help my people and just need some resources to change people’s lives. There’s a lot going on, a lot our elected officials will not address. That’s our reality for people who look like me. There’s no accountability, so how do we teach people to make their elected officials accountable?”

After a CEA session in late February on the Commission on Human Relations, King deemed the CEA “a regurgitation of BS.”

Finch acknowledges that the CEA might not fully address the challenges that people face in their neighborhoods—from language barriers and mistrust of government, to violence and a lack of programming for kids. “The CEA isn’t’ enough, but in a lot of cases, it can be beginning of something,” she said.

But, she says, the CEA can serve as an opportunity for neighbors to come together, have conversations, and start to organize—or at least make personal connections within city agency staff, who in turn, learn more about communities by participating in CEA sessions.

This holds true for Marsha Wall, head of the Southwest Community Advisory Group and founder of Southwest Community Partners, who graduated from a CEA in 2014. She found the CEA useful in providing her contact information for individuals in various city departments whom she could call if she had a complaint. She incorporated the departments’ resources and services to advance her goals for her neighborhood, particularly those related to improving public safety, removing blight, and cleaning up the streets.

“When you’re civically engaged in your neighborhood, resources come to you,” Wall said. “These agencies work for you! You’re their employer. You’re paying their salary. Make them work! Make them earn their pay.”

The city’s hope for the CEA is to empower residents to build deeper, more caring relationships within their communities and use government resources and services to make Philadelphia a better place to live.

“A lot of what we’re seeing in protests here in Philadelphia or nationally is people showing up who have never engaged in political process before, people who see this as turning point,” Dan Gabor said. “It’s either get engaged and shape the future or sit back and accept the end result.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.