Philly police begin limited launch of body cameras

Listen-

-

-

-

-

-

-

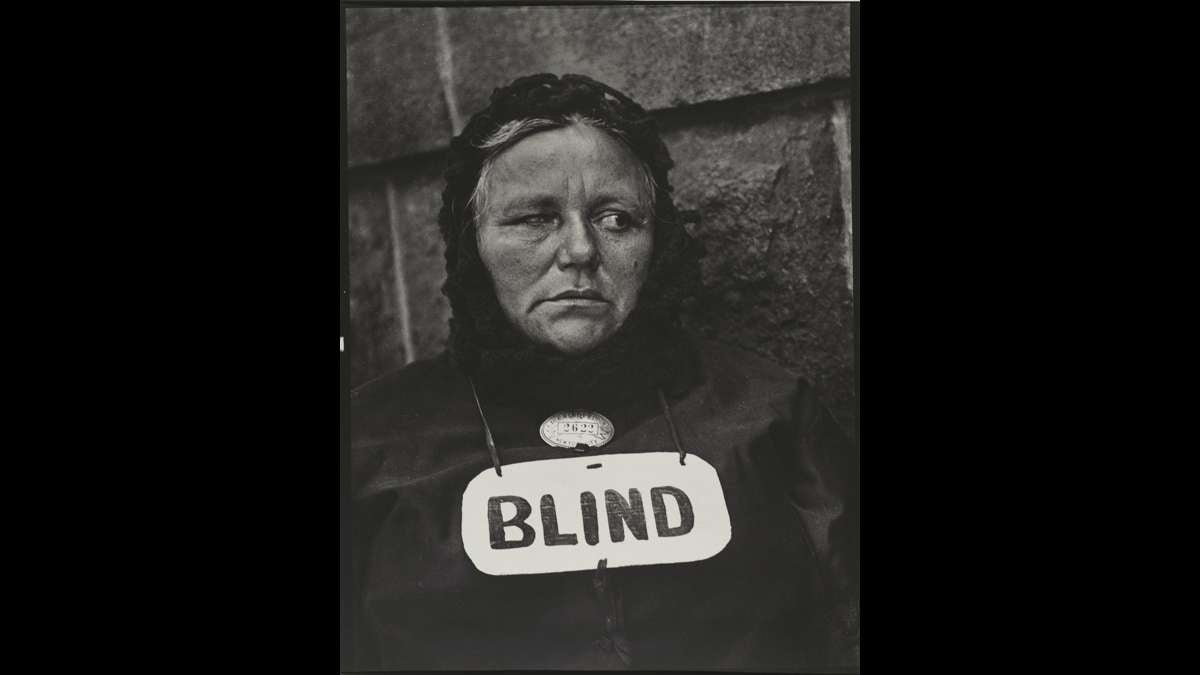

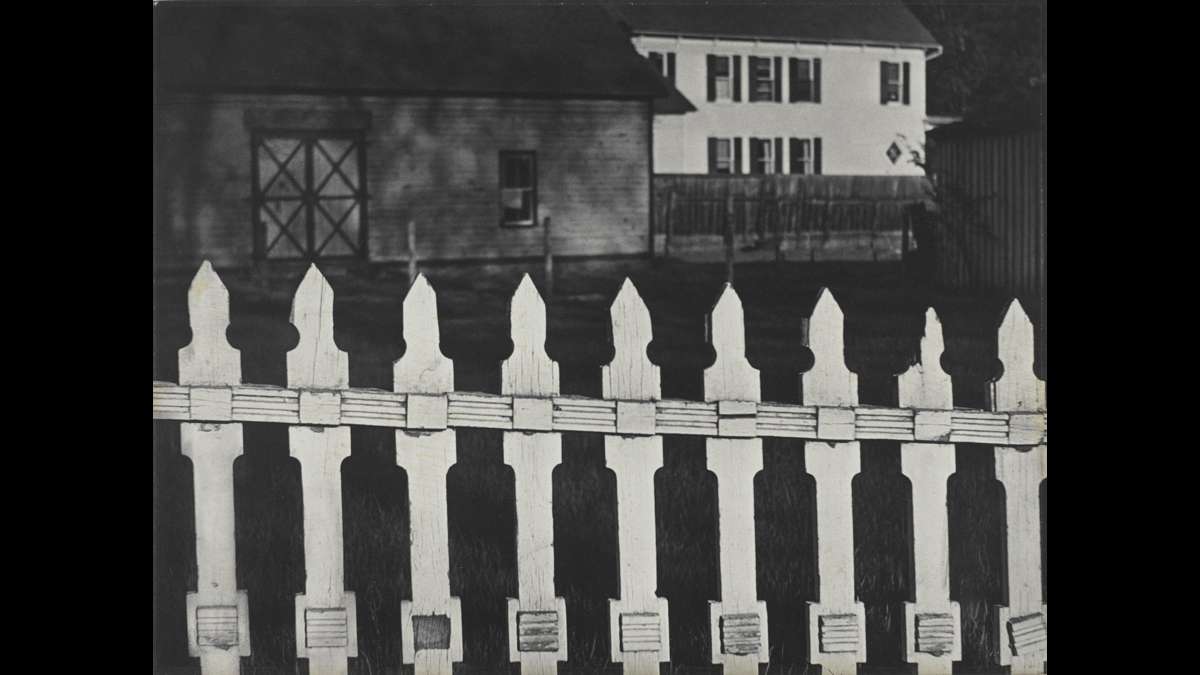

Wall Street, New York, 1915. (Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art)

-

The Philadelphia Police Department launched its body camera program this week, with about 30 officers wearing cameras in North Philadelphia.

The approach has been praised by everyone from community leaders to President Barack Obama. But making cameras work, analysts say, is more than just a technical challenge.

Lindsay Miller, a researcher with the Police Executive Research Forum in Washington, D.C., recently analyzed camera programs for the U.S. Department of Justice. There’s no question that body cameras help keep police officers and citizens on their best behavior, she said.

Among the most comprehensive studies to date, she said, was conducted in Rialto, California, with a population of about 100,000. During the year-long study, officers’ use of force fell by 60 percent, while citizens’ complaints fell by more than 80 percent.

These changes appear to reflect real improvement in relations between police and civilians, Miller said. Officers are less likely to bend the rules and use force unnecessarily, and civilians are less likely to make unfounded complaints.

But implementing a camera program effectively means more than buying cameras, she said. Police departments must consider a number of factors — “everything from when to turn the cameras off and on, how long to keep the data, what to consider when you’re thinking about storing data, responding to public disclosure requests, things like that,” Miller said.

To take just one example, the more video police have, the more video citizens want.

“More and more people know these cameras exist, so more and more people will be requesting videos,” Miller said. “So what happens if an agency says, ‘Well, this is evidence, we can’t release it.’ Or, ‘What are the parameters in which we need to release the videos?’ So those are some of the big challenges when it relates to privacy.”

Her bottom line is that police should plan carefully and implement gradually.

Here in Philadelphia, Councilman Curtis Jones, chair of City Council’s committee on public safety, said he’s glad Philadelphia is starting slow with its six-month pilot camera program. That will help break down mutual distrust between police and civilians, he said.

But important groundwork remains to be done, Jones added. Among his concerns is the effectiveness of the Police Advisory Commission, the civilian panel charged with handling complaints. “Nobody likes it,” Jones said. “So what we want to do is take a look at all the tools available to restore a sense of fairness on both ends.”

The commission has long been criticized by civilians (for being ineffectual) and police (for being intrusive), Jones said. But with cameras on the way, it will be more important than ever that the commission do its job well.

“I care about the police officer that wants to go home to his family after a shift – but I also care about the college kid mistaken for a thug at two in the morning, who gets pulled over and disrespected or worse,” Jones said. “We have to strike a balance.”

Jones sponsored a city charter amendment two years ago that would have strengthened the commission. The good-government watchdog group the Committee of Seventy endorsed Jones’ proposal, but so far it hasn’t gone anywhere.

But the councilman sees an opportunity to go back to the drawing board and give the commission a clearly defined role in handling video-based complaints. Right now, he said, “nobody knows where to deposit a complaint. Nobody knows what their rights and responsibilities are. So there might be a new role for the Police Advisory [Commission] that is not a traditional role, to serve as a conduit to say, ‘This is a complaint that needs to go here, and we’ll track it.'”

Jones said he’ll be meeting with community members, police administrators and representatives of the police officers’ union to try to determine how best to improve the commission.

But he said he worries that budget constraints will undercut the departments’ ability to effectively handle all the new data a full-scale camera program would bring in.

Meanwhile, news from New York City, where a grand jury declined to indict an officer who was filmed choking a suspect to death, points to the limitations of video. As comedian Chris Rock tweeted just hours after that decision: “This one was on film.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that the commission lacks subpoena powers. In fact it can issue subpoenas, but lacks the power to order disciplinary measures based on its findings.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.