Philadelphia refinery capitalizes on the shale boom

Listen

The Point Breeze refinery sits along the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia. (Kellie McGinn/Philadelphia Energy Solutions)

The Valley Forge toll plaza is where route 76 splits from the Pennsylvania Turnpike and becomes the Schuylkill Expressway to Philadelphia. It’s one of the busiest turnpike interchanges with more than 60,000 cars passing through every day. And there’s a good chance the gasoline those cars are running on was made at the 148-year-old oil refinery in South Philadelphia.

[Part five of five]

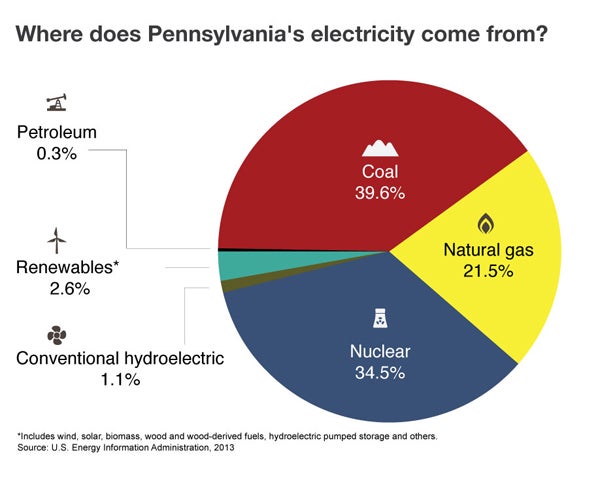

Pennsylvania is third in the nation for energy production. It’s also in third place for carbon dioxide emissions. As the federal government pushes states to cut emissions that are leading to climate change, StateImpact Pennsylvania profiled five major energy sources: coal, wind, nuclear, solar and oil.

Philadelphia Energy Solutions

The Valley Forge toll plaza is where route 76 splits from the Pennsylvania Turnpike and becomes the Schuylkill Expressway to Philadelphia. It’s one of the busiest turnpike interchanges with more than 60,000 cars passing through every day. And there’s a good change the gasoline those cars are running on was made at the 148-year-old oil refinery in South Philadelphia.

Capitalizing on the shale boom

The round drums that store the crude oil can be seen from the Expressway. Inside, the refinery complex sprawls like a city on both sides of the Schuylkill River. It’s one of the oldest and largest refineries on the East Coast. Here, up to 350,000 barrels of raw crude oil get turned into gasoline, jet fuel, heating oil, diesel and chemicals every day.

Most of that raw crude comes to the refinery by train from the Bakken Shale in North Dakota.

“What we don’t have right now is the copious quantities of the Marcellus [Shale] gas,” says Phil Rinaldi, CEO of Philadelphia Energy Solutions. “It sits 100 miles away or 150 miles away.”

Rinaldi is leading a group of business leaders and politicians advocating to build a pipeline to bring that shale gas to Philadelphia. The refinery would use it to generate electricity and to make new products like nitrate fertilizer, but the group hopes a natural gas pipeline could help turn the city – with its ports, rail lines, and proximity to major markets – into a job-rich energy hub.

“I think there’s an opportunity for greater Philadelphia to really develop industrially like we’ve seen in a couple of other places around the world when abundant natural gas was available – the U.S. Gulf Coast, 50 years ago and Saudi Arabia, 25 or 30 years ago,” Rinaldi says.

Refineries third for carbon emissions

But not everyone in and around Philadelphia wants the city to become the next Houston.

At a recent climate change rally outside city hall, Sue Edwards, of Swarthmore, gets choked up thinking about her children.

“I don’t want them to live in a planet where lots of people are drowning and dying of starvation because of droughts, huge storms that swamp people’s houses and threaten their lives,” she says. “I think that’s what we’re facing if we don’t stop using as much carbon fuel.”

Under a new proposal from the federal Environmental Protection Agency, Pennsylvania would be required to cut 32 percent of carbon dioxide emissions from its power plants over the next 15 years.

After power plants, oil and natural gas wells and pipelines are the second largest source of carbon emissions with refineries coming in third, according to the EPA. For now, the agency says it is not planning to regulate carbon emissions from those sectors.

The federal Clean Power Plan has been seen as a win for natural gas, which burns cleaner than coal. However, the petroleum industry has gotten in line to fight the rule.

Back at the climate rally, East Falls resident Karen Melton doesn’t expect the world to move away from fossil fuels in her lifetime.

“It’s not that we can’t do it,” she says. “We’re really up against the people who control much of the economy, much of the political power.”

‘We have choices in Pennsylvania’

Workers in the refinery see things differently.

Two years ago, the energy business in Philadelphia was in trouble. This refinery, once owned by Sunoco, was on the verge of closure until the shale boom unleashed record-breaking amounts of cheap, domestic oil and gas.

John Clark is business manager of the local boilermakers union. Many of his members perform regular maintenance in the refinery, such as welding new pollution controls and scrubbers.

“We live here, we want to breathe fresh clean air like you do, too,” Clark says, “But we also need employment and we need heating oil, diesel fuel, gasoline.”

Many environmentalists see CEOs like Rinaldi as enablers of the country’s dependence on fossil fuels, which is leading to climate change. I ask him how he sees himself.

“Energy is the lifeblood of the world and it’s what makes a difference, and the form of that energy is not destroying. The form of that energy is enabling.” Rinaldi says. “It’s enabling people to live better lives, longer lives, more fulfilled lives.”

Mark Alan Hughes is Director of the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy at the University of Pennsylvania. He says the state has become a microcosm of America’s love-hate relationship with energy. But he argues it could also be the place to reconcile that ambivalence.

“We have choices in Pennsylvania across every possible source of energy generation– of oil, of gas, of coal, of hydro, of solar, of wind and nuclear,” he says. “And so we are the necessary place to work through these issues.”

Otherwise, Hughes says we could all end up paying a much bigger toll down the road.

Credit: Rachel Feierman for NewsWorks/WHYY

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.