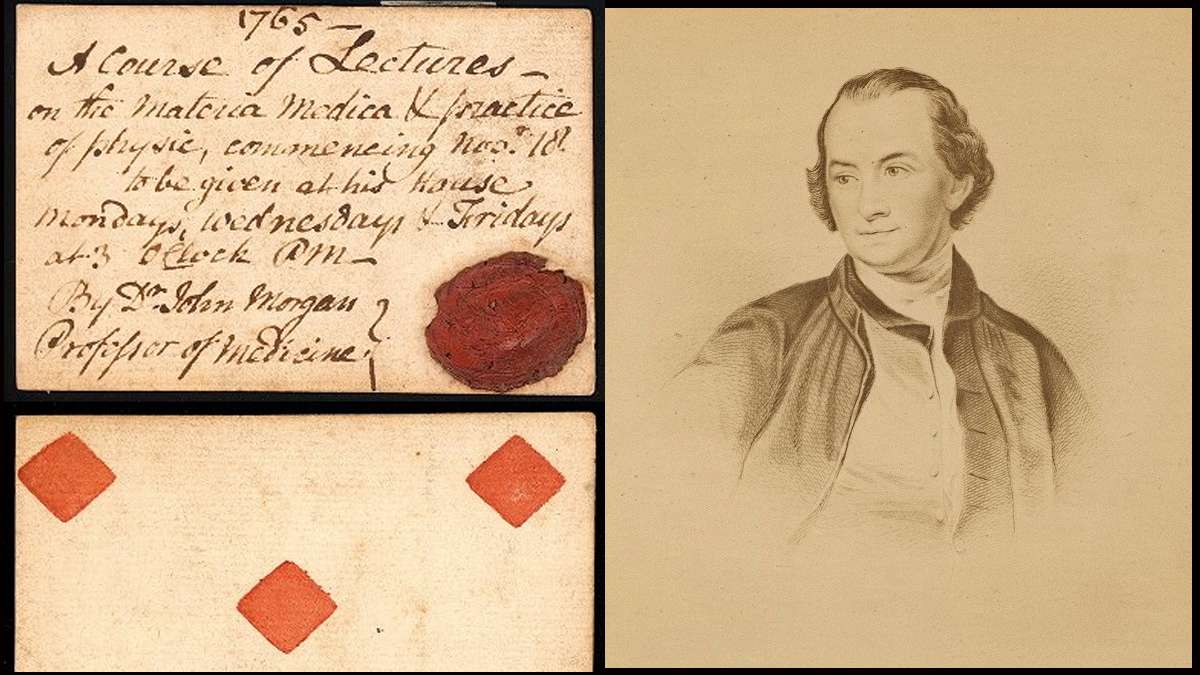

Penn’s School of Medicine — nation’s oldest — turns 250

ListenOn May 30, 1765, Dr. John Morgan stood before hundreds at the College of Philadelphia’s Fourth and Arch streets campus.

The school, which would become the University of Pennsylvania, had invited Morgan as the featured speaker to read his essay, “A discourse upon the institution of medical schools in America.”

“What I am to propose is a scheme for transplanting medical science into this seminary and for the improvement of the healing arts,” he stated.

Morgan’s essay was 113 pages based on one publication (though the pages were small), but University of Pennsylvania archive director Mark Lloyd points out commencement lasted two days.

Morgan’s moment in the spotlight was important, as the college had just green-lighted his proposal to create a medical school. It would be the first in the Colonies. (Kings College in New York followed shortly thereafter.)

What is now officially known as Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania is celebrating the school’s 250th anniversary this month. It’s out with a new book commemorating that history.

Morgan first studied medicine under the wing of Dr. John Redman, a good friend of Ben Franklin, who at the time was also focused on improving the region’s health system.

Morgan went on to the esteemed University of Edinburgh in Scotland, where he and another friend, William Shippen, discussed plans to establish a medical school back in Philadelphia.

At that time, just about anyone could practice medicine in Colonial America. People would apprentice with a doctor who’d then sign off on them.

When he returned to Pennsylvania, Morgan went to leaders of the College of Philadelphia to make his case, saying, “We need a medical school that is a link to a university, a link to some kind of hospital system, that understands and will talk about how what is going on in the body can be determined from anatomy, so that we will understand disease,” according to Dr. Gail Morrison, senior vice dean for education and an alumna of the school.

The college loved the idea, appointed the young Morgan as its first professor of medicine, and started classes that fall.

It was a fairly bare-boned operation at the start. Students would buy tickets to hear doctors lecture on anatomy, surgery, chemistry and pharmacology.

“Today we would chide them for being amateurish,” said Lloyd, Penn’s archivist. “There was not even an organized faculty.”

The American Revolution also hampered the school’s development. Additionally, doctors at that time had yet to discover germ theory and didn’t understand how diseases spread.

“Heaven knows what happened when women were giving birth,” said Morrison.

Despite the many stumbling blocks, Morrison said the model Morgan set up — affiliating medical education with a school and a hospital — was an extremely important start, and one that laid the foundation for medical education today.

Politics, war, a doctor rivalry and depression all played into Morgan’s quickly fading from the school’s leadership, according to Lloyd and Garrison.

He died at the age of 54.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.