Penn T cell immunotherapy shows promise for myeloma

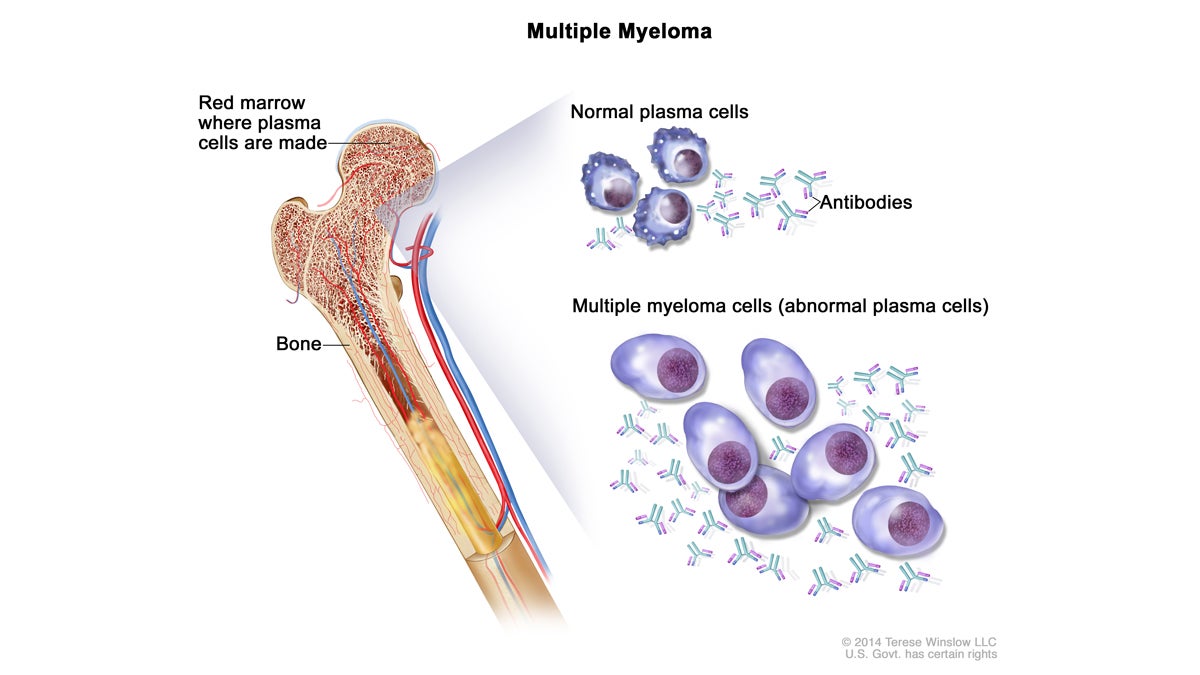

Multiple myeloma cells are abnormal plasma cells (a type of white blood cell) that build up in the bone marrow and form tumors in many bones of the body. (Image via NIH/Cancer.gov)

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have had great success using reprogrammed T cells to treat leukemia. That effort is now expanding to other types of cancers, with encouraging results in the first clinical trial for multiple myeloma patients.

Multiple myeloma is a cancer of bone marrow plasma cells, which spew out antibodies in response to infection.

“Their plasma cells go screwy and start reproducing themselves,” said Edward Stadtmauer, the chief of hematological malignancies at Penn and co-lead author on the new study. “Instead of making lots of different antibodies, you make one useless antibody.”

That extra protein gums up kidneys, and those abnormal cells crowd out good immune cells, leaving patients anemic and prone to infection. Bones become painful and crumbly.

Sometimes, the disease can be treated with a bone marrow transplant. But that option comes with substantial risks.

“Anytime you give someone someone else’s bone marrow, those cells can go into you and see you as foreign and can attack you,” said Stadtmauer.

To get around that problem, researchers turned to patients’ own bone marrow. Then, with genetic engineering, the team also gave certain T cells an extra weapon: a receptor that recognizes myeloma cells, transforming them into targeted warheads.

“Somewhere in the neighborhood of 80 percent of the patients went into beautiful remission,” said Stadtmauer of the trial, covered this week in the journal Nature Medicine. “And at this point, there is a substantial group of patients who have still not progressed their disease, despite having very high risk a disease.”

The results are preliminary, he said, because the trial included just 20 patients. But so far, the treatment appears relatively safe, without some of the major side effects of other cellular immunotherapies.

Compared with previous efforts to use modified T cells as cancer-killing weapons, the myeloma target is highly specific. But it’s not present in all cases of the disease, and it must be matched with other aspects of a patient’s immune system. As a result, Stadtmauer said, the approach is suitable only for about a quarter of multiple myeloma patients.

Patients who did not respond as well were more likely to have quickly lost the reprogrammed T cells from their system — something the team is currently working to better understand so that cell longevity can improve.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.