Penn Museum’s ‘touch tours’ offer blind visitors grasp of ancient history

“We are going to go back 5,000 years, to the first dynasty of Egypt,” said Theresa Joniec, setting her “wayback machine” to 2800 BCE.

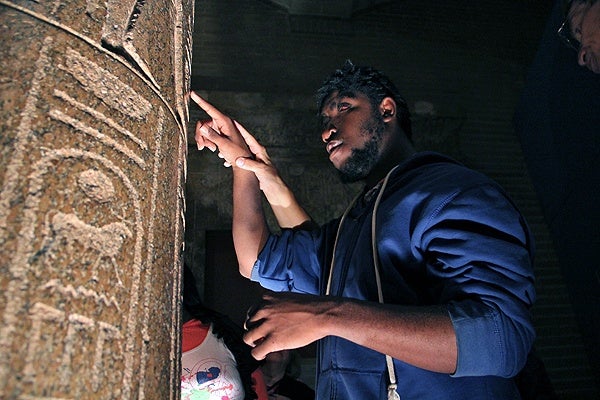

Joniec, a docent in the Egyptian gallery at the University Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, was showing a group of visually impaired visitors a large carved stela — a kind of tombstone made of black basalt commemorating the ancient Pharaoh Qa-a. “DO NOT TOUCH” signs are posted on the walls.

“Go ahead, touch it,” said Joniec. “I’m going to touch it, because I don’t get this privilege. This is 5,000 years old.”

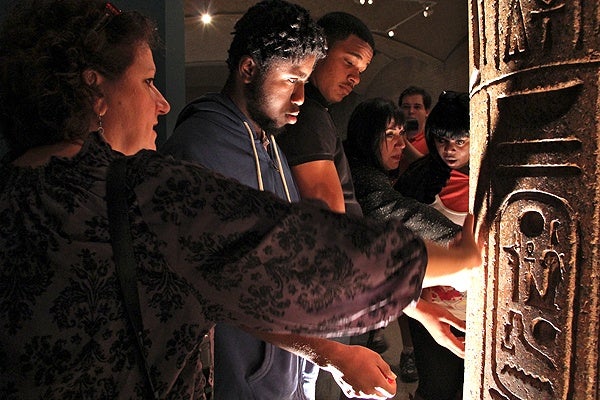

The Penn Museum allows patrons to handle artifacts as part of their new “touch tours” for the blind and visually impaired. After thoroughly washing with sanitizing wipes, several sets of hands roamed over the curve of stone, and poked fingers into carved hieroglyphs. They traced cracks, discovered sand erosion, and felt where gaps in the original carved stone has been filled in by conservators.

“Touch it to the side. See the different texture? This is repaired,” said Joniec, guiding the hands of blind patrons. “They wanted you to know it’s repaired. That’s why it’s a different material.”

Only selected objects in the Egyptian exhibition were available for touching, and only during designated touch tours. Out of the several dozen Egyptian artifacts on display, the visitors were able to handle six, including carved columns, a granite statue, and a sphinx. The tour took over an hour.

“One of the first things we learned was to slow down. We look at things so rapidly, and we don’t stop to pay attention,” said Trish Maunder, the Museum’s coordinator of special tours. “People who use touch will look at an object for much longer, and really look at the details.

“The visually impaired see the comparisons between the constructed and the ancient, and the texture, asking questions — how was it put together and when was it put together. I’ve seen sighted groups go through and they whiz past it in a few minutes.”

Selecting suitable touchstones of ancient Egyptians

With the help of curators, conservators, and blind focus groups, Maunder selected certain objects to be part of the touch tour based on texture, temperature (granite is colder than limestone, for example), body scale (“things that weren’t too high, and that weren’t too wide”), and the ability to tell the story of the ancient Egyptians.

Anthony Coughlan, 19, a senior at Overbrook School for the Blind, used both hands to feel the rounded shape of a large, 4,000-year-old stone vase. He was literally hugging it.

“It kind of cool how it’s made and how they could do it,” said Coughlan. “I never seen anybody nowadays do something like this.”

A Spanish teacher at Overbrook, Rebecca Ilniski, was allowed to bring her seeing-eye dog into the exhibition hall, a serious no-no at any other time.

“It was awesome because we can feel the artifacts. It brings them to life,” said Ilniski.

The docents do not normally get reactions as excited as blind patrons discovering the face of a god carved in stone.

“Touch is our mother sense, and it tends to be the one that we have forgotten how to use in an active sense,” said Maunder. “I think it’s great for everybody. You don’t have to be blind or visually impaired to get pleasure from that.”

However, you do have to be blind or visually impaired to experience that kind of pleasure at the Penn Museum. Touch tours are restricted to those who are blind or visually impaired, and available on select Mondays, when the museum is normally closed to visitors.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.