Penn Medicine residents are demanding better working conditions amid growing unionization efforts

Residents at the Hospital of University of Pennsylvania and Pennsylvania Hospital have joined a growing number of physician unionization efforts.

Listen 4:30

Leah Rethy is an internal medicine resident with Penn Medicine. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Dr. Leah Rethy was pregnant during the first year of her internal medicine residency at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. She gave birth during her second year. She worked through her 40th week so she could save her time off and spend more time with her newborn.

Now she’s back at work, and needs child care. But residents often work long and irregular hours, sometimes as many as 80 hours a week. At the same time, she lamented the wait times for child care affiliated with Penn Medicine are impossible, and finding her own child care or a nanny is prohibitively expensive.

“The cost of day care … in a month is about half of my salary in total, and the cost of a nanny is essentially the entirety of my salary.”

She said this is not an unusual problem — residency follows undergraduate education, and usually four years of medical school, so it overlaps with childbearing years for most women.

“I know a lot of people who’ve delayed having children. And I also have heard a number of stories of people delaying having children and then ultimately having real challenges getting pregnant because of being older and various factors.”

She said this experience led her to support the unionization efforts, believing it’s the best way for residents to demand better working conditions and higher pay, which would ultimately lead to better patient care.

Last month, most residents at the Hospital of University of Pennsylvania and Pennsylvania Hospital decided to form a union. They join other residents at programs around the country, most recently at Montefiore Hospital in New York, and George Washington University in Washington, DC.

Dr. Chantal Tapé, a third-year resident in family medicine, said residents expect the work to be hard, with long hours, but they would also like to be able to be healthy and financially stable so they can focus on taking care of patients.

She said it is “frustrating as someone who is a prenatal care provider … to watch my colleagues and the people that I care about have less access to the kind of care that we would recommend for our patients.”

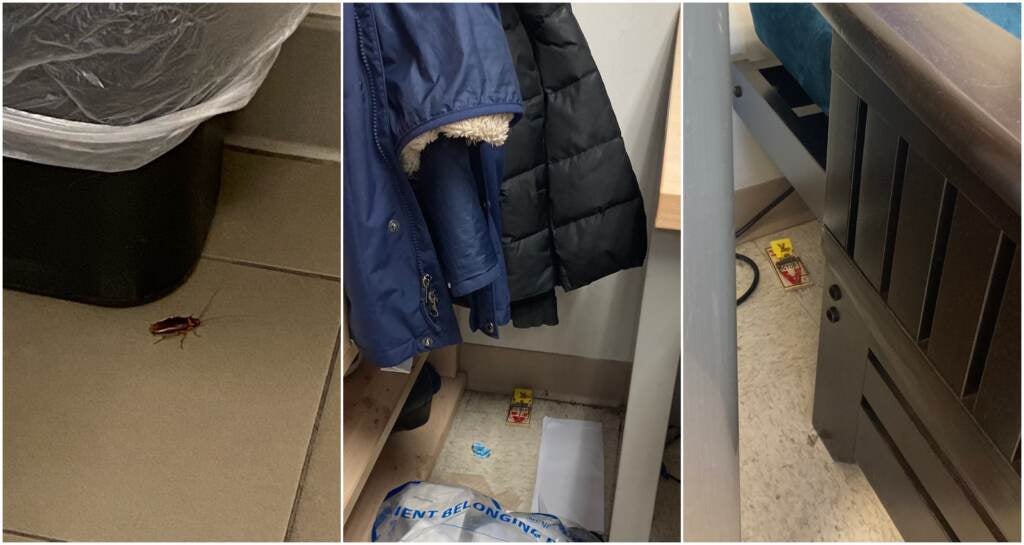

Access to child care is one of many issues residents cite for their decision to form a union. Others include the upcoming loss of parking benefits that would lead to an extra $200 monthly cost for residents who decided where they would live with the benefit in mind; and dirty call rooms, which are rooms where residents stay if they have to work overnight.

Dr. Madison Sharp, a third-year resident in obstetrics and gynecology, recalls not even having a call room to sleep in during a 24-hour rotation.

“So I tried to sleep in a dialysis chair that didn’t lie flat in a conference room off to the side,” she said. “Two years later, residents on that same rotation still don’t have a place to sleep for a few hours on a 24-hour call shift … keep in mind that Penn just opened a billion-dollar hospital but neglected to create physical space for us.”

Penn Medicine did not make anyone available for an interview, nor did they respond to specific questions. In a prepared statement they said they value their residents and “are proud of the ways in which we have sought to continually improve resident life and wellness.” The statement maintains they provide benefits and increased salaries to offer competitive working conditions. Starting July 1, resident salaries will start at a little more than $69,000 a year, according to Penn Medicine. They also say “trainees” should bring their concerns to administrators through an existing advisory council.

“I was the president of this council last year, and I can tell you firsthand that the House staff governing council is extremely limited in what we could accomplish,” Dr. Sharp said. “It was incredibly frustrating to advocate for residents and fellows and not be heard or have our concerns brushed aside or dismissed. And after struggling to advocate on behalf of my colleagues as president and not being listened to, it became clear that a union was the only way to truly advocate for ourselves.”

Dr. Jackson Steinkamp, an internal medicine resident, said this also extends to issues that affect patient care. For instance, he said Penn Medicine installed a CT scanner at the new building at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, which is staffed overnight. But that means the CT scanner at an older building is no longer staffed after hours, so intensive care patients who need one of these scans must be wheeled over to the new building. He said residents, nurses, and attending physicians claim Penn Medicine has left the issue without any fix, despite their requests.

“It feels like those kinds of issues are not being heard by the people who actually would be able to be in a position to hire a new tech … to staff the CT scanner, for instance.”

The residents filed a petition with the National Labor Relations Board to unionize with the Committee of Interns and Residents, which represents resident physicians around the country. Communications director Sunyata Altenor has worked with this organization for 10 years, and she says there was not always as much interest in unionizing.

“Every week we’d have a handful trickle in and that would be normal in most of the history here,” she said. “Once COVID hit, we were seeing 20, 30, 40, 50 inquiries come in on a weekly basis.”

Altenor said residents who want to unionize understand the program is supposed to be hard work, with long hours. But they want to be treated fairly for their efforts, at a workplace they cannot just choose to leave, as it’s a required part of their training.

“It’s easy to exploit physicians during this time in their career,” she said. “They’re only going to be there for a few years. It’s sort of expected that you go through this hard hazing culture and then you come out at the other end an attending physician.”

Residents at the University of Vermont Medical Center voted to form a union last year. Dr. Kaley Kinnamon, a third-year neurology resident, said negotiations are taking longer than anticipated, and they have similar priorities to residents in other programs: parental leave, better workplaces, and compensation for taking extra shifts. She said the drive to unionize comes down to residents being at the bottom of the hierarchy in health care.

“They’re the people that are always there in the hospital … if you’re coming into the hospital after regular work hours, chances are that the person that you’re going to be seeing is a resident or a fellow,” she said. “When you’re left with all of that burden and also when … financial losses and things like that tend to affect you first, like that causes a lot of frustration and anxiety.”

Following the successful union vote for residents, support staff including maintenance workers and technicians are unionizing as well.

The union for residents at Jersey City Medical Center has already argued for a better work environment in the years since they’ve organized, said Dr. Andrea Attenasio, a fourth-year resident in orthopedic surgery. For instance, she said they managed to ask the hospital to provide food for residents who work after hours; to provide bedsheets for the rooms where residents stay if they work overnight; and to stop tying salary increases for residents to overall hospital performance, a major concern with rising inflation and cost of living.

Jersey City Medical Center said they could not accommodate an interview request.

Dr. Attenasio said the bargaining power and strength in numbers that comes from being a union member makes a difference for residents, who are matched with a site based on an algorithm, and cannot easily change their workplace should they have issues.

“It’s an automatic support system and it allows you to go to your hospital administration as a united front.”

Disclosure: Penn Medicine is among WHYY’s financial supporters.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.