Outside looking in: Women fight eviction date from local homeless shelter while men’s side stays open

Tanya Curry first slept in a homeless shelter when she was in her early 20s and had her 5-year-old son alongside her. Today at 46, she is alone and once again homeless.

The homeless women staying at Fernwood East found a safe-haven at the shelter, but they are scheduled to be kicked out on March 28. (Pixabay)

This story originally appeared on Philadelphia Weekly.

—

Tanya Curry first slept in a homeless shelter when she was in her early 20s and had her 5-year-old son alongside her. Today at 46, she is alone and once again homeless, an experience she was determined to never repeat.

“There was a lot of anger and resentment in the beginning, because I couldn’t understand how we did all the right things and I still ended up here,” said Curry, whose home foreclosed after her husband, the main income provider, died in 2016. “I did everything I was supposed to do.”

Suffering from multiple autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and a thyroid condition, Curry has trouble staying in certain shelters due to the exposure rate to diseases. Gaudenzia House of Passage (111 N. 48th St) is one such place that posed a particular problem for Curry, since she had to sleep in a chair throughout the night — an antiquated sleeping arrangement that many shelters like House of Passage still implement. Unable to remain in a chair throughout the night, Curry resorted to sleeping in a car and eventually squatting in an abandoned house in Mt. Airy.

Curry has mentally coped with her situation by reminding herself of two things. Firstly, she does not have a child with her this time around. Secondly, she has found an oasis in the women’s shelter of Fernwood East (7979 State Rd).

But Fernwood East, complete with programming and case management services that help Curry and an estimated 40 or so women “get through this” difficult stage, is about to be closed down. A first-time temporary emergency shelter during the winter months, all the women at Fernwood East have been given until March 28 to find a new living situation. RHD Fernwood, the year-round shelter for men at the same location will remain open.

With that knowledge, Curry and eight other women from Fernwood East took to City Hall. Waiting outside the office of Councilwoman Jannie Blackwell, the women came to plead their case about keeping the shelter open or at least gain an extension. In the end, they were able to speak with representatives for the councilwoman, but not directly with Blackwell.

“Our city needs more transitional housing for people who are in the position they are in at Fernwood,” Blackwell said to Philadelphia Weekly about the matter. “This is one of the issues we should discuss at our budget hearings. We need more funding for shelter, transitional and low-income housing for residents of our city.”

Due to lack of resources, the deadline for Fernwood East’s closure stands firm. It is a countdown to eviction as well as insurmountable uncertainty for the women who have grown friendships and mentorships in the more reclusive area by the Curran-Fromhold Correctional Facility.

Annie Marlo, 37, has been homeless for three months and stated that Fernwood East has been a blessing in disguise. Waiting with the other homeless women outside Blackwell’s office, she explained that they came on behalf of all of the women back at the shelter, many of whom were unable to come due to old age, disability and/or sickness.

“I have to honestly say it’s not like the other shelters. This one, it’s very much like a home,” said Marlo. “It’s up to you to do something with your life. We have a really strong staff there. They are self-motivating, trying to help us do the best that they can.”

For Curry, Marlo and the women of Fernwood East, the shelter’s closing is not just a personal matter. Instead, they believe it is yet another example of the system turning a blind eye toward women who need immediate relief and are unable to sleep in chairs of overcrowded shelters or wait for slow-moving government assisted housing.

“We need more women shelters, there are a lot of women out here on the street,” said Curry. “And if this hadn’t had happen to me, I would have never noticed, you couldn’t have told me that that these shelters cater to the men.”

Curry’s judgment of the number of homeless women is not just perception, it’s reality.

While historically more men experience homelessness, Liz Hersh, director of the City’s Office of Homeless Services (OHS) explained that the number is decreasing. What is increasing is the number of homeless women. As of Jan. 25, 2018, based on the City’s annual Point-in-Time count, 2,049 women and 2,631 men were in Philadelphia shelters. The overall total number of unsheltered and sheltered homeless people in Philadelphia was 2,311 women and 3,439 men.

It is a “shift in demographics,” not only in regards to gender but also age. Hersh noted that previously women who entered the shelter system were typically with children or pregnant, but she has seen a growing rate of elderly women coming in alone.

Philadelphia currently has a total of 12 family shelters, six for people who identify as women and seven for people who identify as men. The figure for shelters does not include respites, such as Prevention Point sites and the Navigation Center in West Philly, both of which are co-ed.

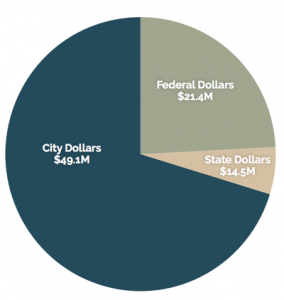

OHS receives a growing yearly budget of about $85 million, mainly from the City of Philadelphia, and allocates approximately $42 million of it to emergency shelters. Last year, OHS served 8,500 people through its emergency housing program.

In accordance with Philadelphia’s five year plan for the homeless assistance system, OHS said it is placing more attention on and funds in homeless prevention and permanent supportive housing (PSH). From its annual budget, money has been directed towards creating 400 new long-term housing options. As part of the Blueprint to End Homelessness Program, a partnership with Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA) and the Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services (DBHIDS), OHS provides 500 housing opportunities each year through public housing units or Housing Choice vouchers.

“[The closing of Fernwood East], it’s a heartbreaking situation. It is 100 percent a money issue with all of this stuff,” said Hersh, who also commended the women for being self-advocates. “I think sometimes we forget that people experiencing homelessness are people, and they form bonds and relationships and friendships and sometimes these shelters are really wonderful places for people to stay for a time. So we’re going to do everything we can to try and figure out a next step for them.”

Hersh elaborated that the next steps for the women of Fernwood East would be to try and get them a security deposit through Rapid Re-Housing, which provides short-term rental assistance and supportive services. If the women qualify for PSH, Hersh said that they can “get in line.” Eligibility is based on the national metric of vulnerability, which is as opposed to past procedures that weighed in on how long someone has been in the shelter system or on the waiting list.

Josh Kruger, communications director of OHS, explained the housing system’s waitlist is just one of the “enduring myths that’s baked into people’s minds.”

Having personally struggled with drug addiction and spending time on the streets, Kruger, a former PW columnist, explained that many old practices which have been phased out and misconceptions of the system are still deep-seeded in the homeless population’s collective consciousness. One old rule that Kruger mentioned is that everyone in the shelters need to leave by 7:00 a.m., but it is protocol that is “just not true any longer, at least in the Philadelphia system.”

Most of the homeless women interviewed at City Hall attested that they have had to leave the shelters in the early hours and come back at night. They said the ability to move more comfortably in and out of Fernwood East is one of the shelter’s benefits.

Another long-time practice that is being transitioned out is the use of chairs for sleeping. It is a tactic that Hersh said her department “hates the most,” but is still prevalent particularly during Code Blues, times when the temperatures feels near or below 20 degrees Fahrenheit. Hersh explained that the department has directed funds towards installing 200 new beds in the shelters by year’s end. The owner of the House of Passage building also recently opened another room to fit 36 more beds, which should phase out the need for chairs on a regular day-to-day basis.

Jennifer Upright, 48, is still not looking forward to the possibility of returning to the House of Passage, or as she calls it, “House of Pain.”

Diagnosed with post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and schizophrenia, Upright has been in a revolving door of living situations, staying at psychiatric hospitals, being released to dead-end and unsafe living situations and winding back up at shelters.

“I got out of a mental rehab and I had no place to go. My son sent me to his girlfriend’s father’s house. It didn’t work out. He had bed bugs and stuff, and I had to get out of there,” Upright recalled. “So I went back to Friends Hospital, got rid of all the bugs and still had no place to go.”

Upright explained that the shelter system is scary enough for a woman living on their own, but dealing with the voices inside her head, a symptom of schizophrenia, makes the experience even more terrifying.

“Keeping Fernwood open is an immediate threat to our well-beings,” explained Upright. Upright added that the staff at Fernwood makes sure she gets her medication and the location’s relatively calmer environment helps alleviate some of her debilitating fears.

Talisha Walker, 27, also has schizophrenia as well as clinical depression and anxiety. Walker was thrown out of her house in the Northeast once her mother discovered that she was pregnant. In her third trimester, Walker remembers her first night without a home.

According to Walker, she went to the OHS and waited from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., without seeing a case manager. She was ultimately placed in House of Passage and had to sleep in a chair.

“It’s different, because you are around all different types of people and a lot of germs. It’s a new experience for me,” said Walker.

After spending some time at House of Passage, Walker was given a bed at Fernwood East. She said Fernwood East provided a more dignified living situation for homeless women and that through a program at the shelter, she has been able to save money to secure some type of housing of her own.

“For my future, I hope to have a place for my son, [live on my own and] be able to stand on my own two feet and not depend on anybody,” said Walker. “I don’t want to have my baby in the shelter.”

Walker said she takes herself to the doctor for her mental wellbeing and prenatal care. What she needs the City for is housing, but right now, she remains on a long waiting list.

“They say that women and children and pregnant women are the first priority but it doesn’t seem like it, it seems like they are just ready to put us out on the street,” Walker challenged.

Hersh explained that the demand for permanent housing far surpasses the City’s current resources. The last time Hersh looked at the 2019 numbers, between 500 and 600 people in OHS’ shelter system were over the age of 62 and had a physical disability or mobility issue.

“This is a really messed up national crisis of people who have all kinds of physical and mental problems. We don’t, as a society, really take care of them. It’s horrifying and it’s wrong,” said Hersh. “We move heaven and earth to help people within our system, knowing that there’s immense suffering out there and that we may not be able to fully alleviate, even by doing everything we possibly can.”

Sharon Bryant, 57, had previously lived in transitional housing, an interim living situation for those looking to gain more permanent housing. According to Bryant, the housing she stayed in was run-down and infested with bed bugs. Although she said transitional housing can cost anywhere up to $400 a month to live in, her house was dilapidated and repairs were rarely made.

“It was so bad, it should be condemned,” Bryant said.

Originally from Jacksonville, Florida, Bryant’s aunt brought her to Philadelphia after she fell ill. After staying with her aunt for about six months, Bryant then entered the shelter system. According to Bryant, it would take two months before she could secure a bed.

Denise Young, 59, has been homeless for a year now. Like the other women who came to City Hall, she too has credited Fernwood East for its “empowering” programming, from savings programs to self-esteem workshops. Also like the other women, Young came to City Hall in search of help not just for herself, but also for her shelter community.

“I’m concerned because a lot of women are pregnant, some of the women are mentally ill, and they have nowhere to go. I have nowhere to go,” said Young. “So the problem is that we are going to be in a transition if they don’t get an extension, and some of the women we don’t want them to get lost.”

Showing unity in a bleak situation, Young gave parting words on what needs to be done: “They need to find more money and we need more prayers. More people need to help out.”

This article is part of Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project among 22 news organizations, focused on Philadelphia’s push towards economic justice. Read more of our reporting at brokeinphilly.org.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.