During opioid crisis, Camden leaders put life-saving needle exchange in peril

-

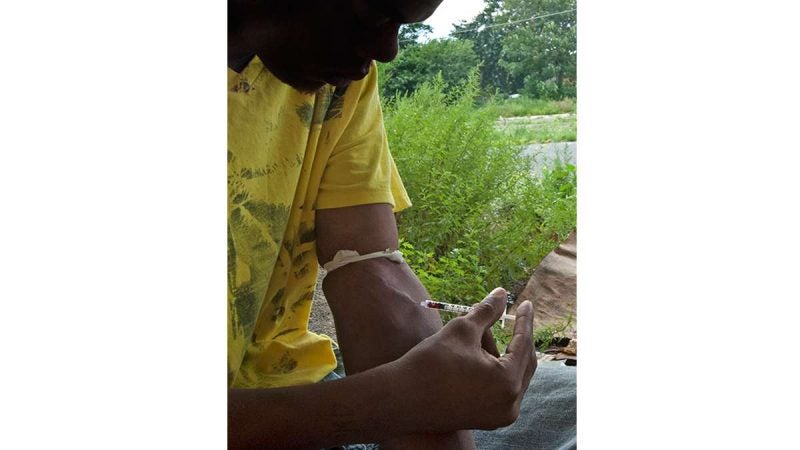

Shooting heroin in a vacant lot in Camden. (April Saul/for WHYY)

-

At the needle-exchange van in Camden in 2014, HIV-prevention team leader Sam Myers (left) talks with Nicholas Brown, who is exchanging syringes. (April Saul for WHYY)

-

At the needle-exchange van in Camden in 2014, HIV-prevention team leader Sam Myers (left) talks with Nicholas Brown, who is exchanging syringes. (April Saul/for WHYY)

-

The approved site for the AHEC needle-exchange van is this parking lot at 271 Spruce Street; the Camden Office of the City Attorney located and approved the site, but Mayor Dana Redd has yet to sign off on it. (April Saul/for WHYY)

With a staggering 64,000 Americans killed by drug overdoses last year according to the Centers for Disease Control, needle-exchange programs could be viewed as life-saving resources that keep HIV and hepatitis C transmission at bay and offer addicts pathways to recovery.

But not in Camden, where a van that served 250 to 350 addicts a week has now been shut down for over a year by lawmakers who apparently care more about the city’s image than public safety.

The death knell for Camden’s program seems to have sounded in the summer of 2016, during a showdown in a vacant lot in South Camden.

On one side was the van that for a decade had offered fresh needles, HIV testing and other services under the auspices of AHEC, the Camden Area Health Education Center.

On the other was Holtec International, an energy company that had won $260 million in tax credits to move to Camden. The lot on Broadway where the van parked two days a week was near Holtec, and construction work was making it impossible for the van to get through..

Sam Myers, an HIV-prevention team leader who had staffed the van for four years, asked to speak to someone in charge; a half-hour later, said Myers, a man who said he represented the company appeared.

“He said,” recalls Myers, “‘Sir, let me explain something to you. Let me tell you how much money is coming down here.”

The man gestured toward Broadway.

“‘You see this street? It’s being moved because it’s in my way. We’re going to move the oldest street in the city to do what we want to do. You’re not going to be here any more.'”

Like many actions in Camden that punish the vulnerable, the van’s eviction by a corporation was all about money. “Holtec International is a member of the Camden community and we care deeply about the health and safety of Camden citizens,” said Holtec program director Ed Mayer, “but we have a secure facility and the van can’t be on our property.”

Holtec’s response was more straightforward than that of city leaders, who now appear to have used the company’s move to Camden as an excuse for giving Myers — along with AHEC Executive Director Martha Chavis, and N.J. state director for Drug Policy Alliance Roseanne Scotti — a two-year runaround as they tried to relocate the program elsewhere in the city.

The trio, worried about displacement for the Holtec project, had started to look for another site in 2015. For a year, Myers said he was a constant visitor to City Hall; a memorandum of agreement was finalized through the city attorney’s office in the fall of 2016. In April of this year, Chavis was notified that a city-owned parking lot at 271 Spruce Street on a virtually empty block was chosen and approved by the city attorney’s office for the van’s use two afternoons a week.

Yet Mayor Dana Redd still has not signed the agreement. At a City Council meeting in June, said Chavis, Councilman Angel Fuentes promised to “follow through” with the Mayor’s office. But neither Fuentes nor Redd have returned the calls of Chavis and Scotti or responded to my inquiries.

It is especially confusing, said Chavis, because the program had been a success, with a return rate of two to three needles for every four given out. “The city,” said Chavis, “has been so responsive and open in the past…we’ve gotten proclamations from them!” In July of this year, Chavis said she had to return $93,000 in state funding and lay off an employee because the exchange was at a standstill.

In 2004, Camden and Atlantic City were the two New Jersey cities so eager to adopt needle exchanges that city leaders volunteered to implement state-run programs. At the time, about half of New Jersey’s 62,000 HIV or AIDS cases were attributable to intravenous drug use; Camden even passed a city ordinance to establish the program. Similar programs continue to operate in Newark, Jersey City, Atlantic City and Paterson.

Nationally, needle-exchange programs — though controversial — are gaining momentum. In Pennsylvania, giving out sterile needles is illegal, so Philadelphia lawmakers use an executive order to authorize a syringe-exchange program through Prevention Point Philadelphia that is credited with drastically reducing the rate of HIV transmission. In Indiana during an alarming 2016 HIV outbreak, then-Governor Mike Pence overcame personal convictions to issue an executive order permitting the dispensing of clean needles. Many conservative states are now considering the programs, and Las Vegas just introduced needle-exchange vending machines.

It has been 13 years since the late Camden activist Frank Fulbrook led the fight locally, saying: “It’s a pathetic situation we have here in this state where saving lives is viewed as a crime. Saving lives trumps all the other arguments.”

Ali Sloan-El, then a Camden City Councilman, calls Fulbrook a “trailblazer” who opened his eyes to the need for the needle exchange. “Back then, the HIV epidemic “was full-blown,” says Sloan-El. “Now it’s contained, but you don’t want it to spread again…the Mayor and the others? They don’t want to see that world.”

In 2014, Emily Reid was a pale young drug addict living in abandoned buildings; she’s been clean for a year and said the Camden van helped her a lot.

“I knew when I was out there, if I didn’t have a clean needle, I would just pick one up off the ground or ask someone to use theirs,” said Reid, “because I needed the drugs and I couldn’t wait. So having the needle exchange always insured I didn’t put myself more at risk than I already was.”

Sam Myers believes Camden will not restore the exchange. “The city obviously doesn’t want this to happen,” he said. It’s short-sighted, said Myers, because “A syringe costs 10 cents to make, but a person who has HIV costs a half million to keep him alive.”

Myers attributes opposition to politicians who view it “as a blight that will keep people from coming to the city” and residents who wrongly consider addiction a choice instead of an illness. In a minority community, said Myers, some resent hosting a van that serves mostly white suburban drug users, and equate syringes with the prostitutes so ubiquitous on Broadway. Myers said the addicts behaved well at the van “because they knew the necessity of what we were doing. The gratitude was overwhelming.”

Perhaps — like the Ohio councilman who recently proposed that emergency crews not respond to an overdose victim who has required two previous interventions–we have lost not only our patience, but our humanity in the midst of the current epidemic.

Still, at a moment that Governor Chris Christie — appointed by President Trump to lead a national opioid prevention task force — has compared drug deaths to the 9/11 attacks, dumping the needle exchange would be a shameful act in a city that can’t afford to pretend away its problems.

Martha Chavis can’t understand opposition to a program that saves lives.

“One of the things I love about Camden is our humanity,” she says. “It sets us apart, regardless of the ills around us. I just don’t get it.

__________________________________________________________

April Saul is a Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist who lives in Camden, New Jersey. She writes about the challenges and joys of the residents in Camden on her Facebook page CAMDEN, NJ: A Spirit Invincible. Several times a month she writes essays on Camden for NewsWorks.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.