On Wolf Street, three immigrant mothers came together to form a ‘beautiful’ family

Women account for a growing share of Latin American immigrants settling in the U.S. In Philly, three mothers share resources to thrive in their new home.

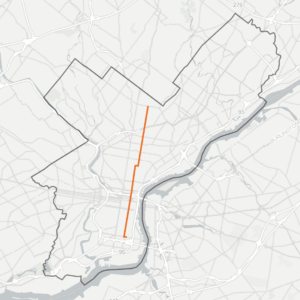

This story is part of The 47: Historias along a bus route, a collaboration between WHYY’s PlanPhilly, Emma Restrepo and Jane M. Von Bergen.

This article is written in English. To read this article in a combination of English and Spanish, click or tap here o para leer este artículo en español, haga clic o toque aquí.

When Marta Caj was running late, she’d grab the Route 47 bus to her job at Las Amigos Bakery in South Philadelphia.

The bus is steady, reliable — an urban workhorse that moved 16,299 people a day, pre-pandemic, on its 10-mile route linking Latino neighborhoods in North and South Philadelphia.

It’s nothing like the buses that Marta encountered traveling with her daughter, then five, on their three-month journey north from Guatemala in the summer of 2019. At one point, Mexican officers boarded the bus and asked for documents. The two people Marta was traveling with had to leave.

As she and her daughter sat in the third seat, the officers stood right in front of them, but didn’t ask her anything.

“I don’t see it as a work of chance, but as a work of God,” said Marta.

These days, Marta lives closer to her job, within a short walk. In her new home on Wolf Street, she shares resources and child care with two other women, one from Guatemala and one from Honduras. Their last names are being withheld to protect their privacy. Marta and Sandra, who both work, live together and pay the third, Jaime, who lives nearby, to care for their children and hers. They cook for each other, talk about their days and celebrate special moments. They are family.

“This is a very beautiful coexistence and friendship,” she said.

On her way to the bakery, Marta passes Route 47 bus stops while crossing Seventh and Eighth Streets. More than a third of her neighbors take public transit to work: The bus is a neighborhood fixture, almost a friend.

But in Mexico, as she was heading north in the summer of 2019, the bus trip was hardly friendly. A gang stopped the vehicle, beat the driver, and pointed guns at the passengers, forcing them to kneel outside. They demanded their money. The criminals took them to a place they did not know and released Marta and her daughter, along with the others. Her daughter, Krishna, now six, is still affected by what she saw on the trip.

“She no longer behaves like a little girl,” Marta said. “Her mentality is different. It changed her psychologically. She saw things she shouldn’t have seen.”

Guatemalans, Hondurans and El Salvadorians constitute a growing proportion of migrants crossing southwestern borders, outpacing Mexicans. In 2019, when Marta was headed north, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection office recorded 264,168 migrants from Guatemala compared to 166,458 from Mexico.

Corruption, lack of jobs, loss of crops due to climate change and violence —including domestic violence — are among the factors motivating women to leave their home countries. And when they do, they face risks men don’t face on what has become an increasingly perilous journey.

Like Marta, more women are taking the risk. About 25% of migrants taken into U.S. custody at the Mexican border are women, up from 13% in 2012. In 2017, one in three children stopped at the U.S./Mexican border were girls under 18 from Guatemala, Honduras, or El Salvador – girls like Krishna.

Marta faced many hardships on her journey, but along the way, there were also moments of kindness and luck. A Honduran man cared for her when she was sick, bringing food. After a grueling experience crossing Rio Grande and carrying Krishna on her back as she ran toward safety, Marta was detained in Texas where she found a lawyer who helped her win a case for immigration based on fleeing domestic abuse.

In Philadelphia, the brother of a hometown friend paid for airplane tickets so Marta and Krishna could come live with his family while she searched for work.

“Everything that happened to me, God had already predicted,” Marta said. “My path was going to be hard for me, to understand the value of things.”

While job-hunting, Marta spotted a ‘help wanted’ sign in the Los Amigos bakery window on Ninth Street. She told the owner that she didn’t know English or baking, but promised to learn. He called three days later. She started to work that day.

“This is how I got to this blessed bakery where I have met many people. It is my first job, which I will always carry in my heart,” she said. “He opened the doors for me without knowing me, without asking me anything.”

She soon met the other two women who would become her Philadelphia family and a beautiful friendship began.

The three women have four children altogether. There’s Marta’s daughter along with Sandra’s son David, 6, and Jaimi’s two boys, David, 7, and Jose, just a few months old.

“It’s very beautiful because we help each other,” Marta said. “When I did not have, the other had, and when the other had not, I had. Between the three of us, we help each other.”

The bakery owner, her other friends, and her housemates – she’s grateful to them all.

“These people come into your life without knowing you and treat you well,” she said. “They are not your own blood, but they are there, they are always there.”

Building a life in a ‘lonely country’

In Guatemala, Marta worked from 6 in the morning until 11 at night, sometimes longer, selling fruit to feed her daughter and two sons “because with your own business, a day you don’t work is a day you don’t eat.” Marta wanted more for her children.

In Philadelphia, she appreciates an economy that allows her to work eight or nine hours a day instead of 15 — and a local culture that she describes as “polite” and law-abiding.

“It is a different culture. Here, there are laws,” Marta said. “Here, they are respected. Here, principles and values apply.”

The children too have a better life. Even though Marta thinks American parents overprotect their children, young people have a chance to get an education here and don’t have to work, as her sons did, when they helped her sell fruit.

Marta has no regrets about building her life in Philadelphia, yet it has come at a heartbreaking cost. She had to leave her two sons behind. Now 15 and 12, they live with her grandmother. Marta sends money and talks to them often. They’ve been earning good grades, pointing to a brighter future. “I realize that the sacrifice was not in vain,” she said.

“Maybe I couldn’t give [them] things that I can give [them] now. Maybe now they have material things,” she said, but “I can’t be with them.”

And it’s painful.

“There are times when I eat or am in a place eating and I stop eating,” she said. “Being away from your children is the worst thing that can be. You never have peace. You wake up thinking if they ate, if they are well…”

“You arrive and it is a lonely country,” she said.

In her loneliest days here, Caj longs to hold her sons in her arms. “There is nothing like coming home and hugging your children.”

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

WHYY is one of over 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow us at @BrokeInPhilly.

Subscribe to PlanPhilly

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.