NJ museum displays massive mural a jailed man created from sheets, hair gel, and newspapers

ListenA Pennsylvania man engineered his mental escape from prison through creation of a towering artwork, mailing it piece by piece beyond bars.

A few years later, he and his composition are freely visible.

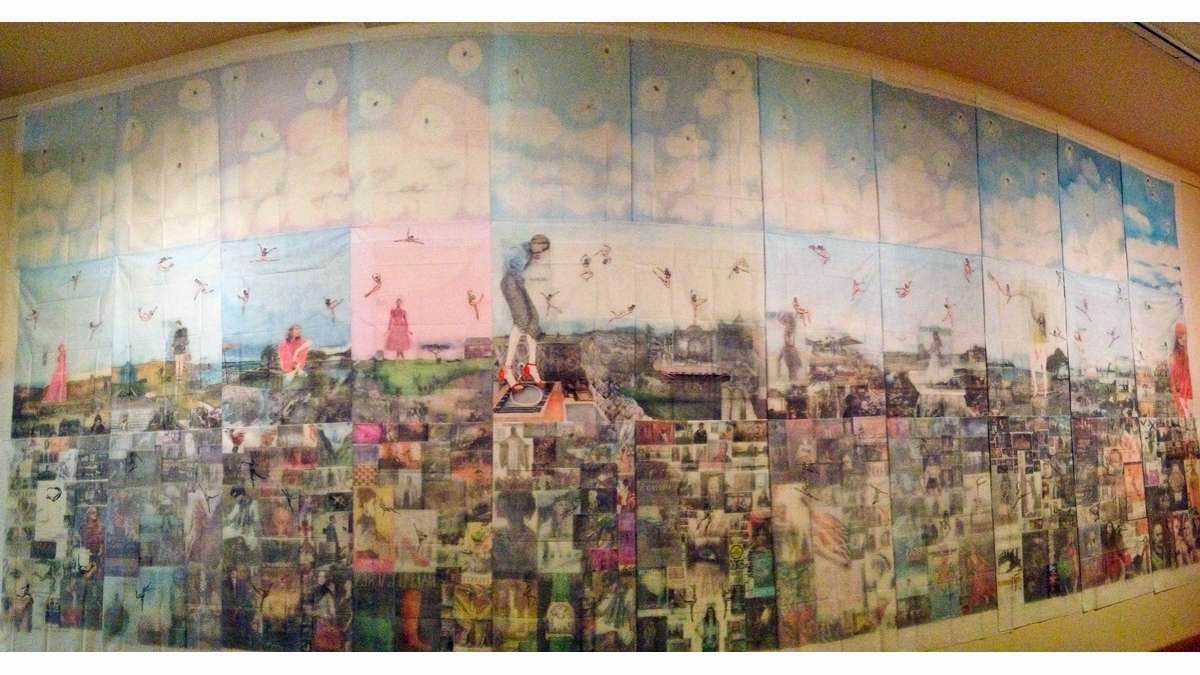

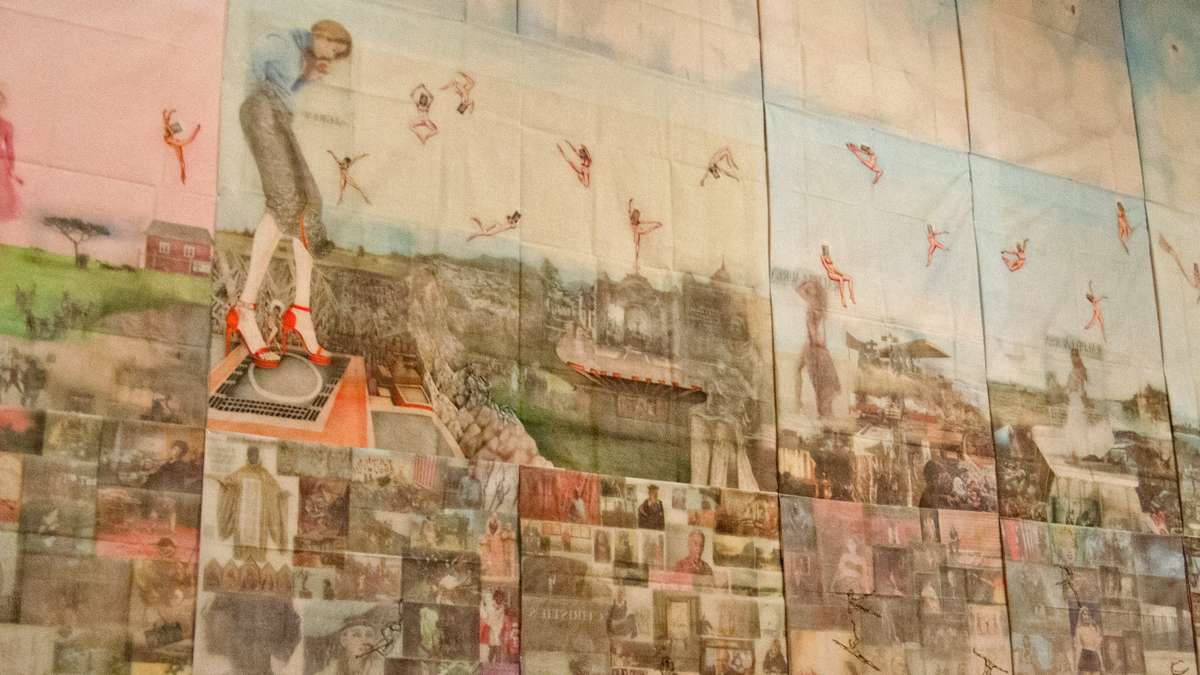

Jesse Krimes’ “Apokaluptein 16389067” is so massive that it dominates an entire wall at Rutgers Zimmerli Museum in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Measuring 15 feet tall and 40 feet long, it’s made up of 39 configured panels.

Krimes assembled the work from familiar images: the destruction from the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, for example, the uprising in Tahrir Square, the ubiquitous Taylor Swift. But, when you back up, you see the mural is organized in three horizontal tiers that the artist says represent heaven, earth and hell.

“The reason that I chose ‘Apokaluptein’ for the title is because the Greek origin of apocalypse means to uncover and reveal,” said Krimes. “But the contemporary translation of apokaluptein, which is apocalypse, is this kind of massive scale destruction.”

And 16389067 was his prison identification number.

“So there’s this kind of correlation between a loss of identity and destruction on a personal level,” he said. “But also using this work as a way to uncover and reveal things that are going on within the prison system.”

‘Apokaluptein’ is more than a conceptual piece of art made by a former inmate. Krimes said creating the piece was “definitely a means of survival.”

A traumatic beginning

Born when his mother was just 16, Krimes grew up in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

“I was raised by who I thought was my biological father,” he said. “But I found out around 10 years old that he wasn’t. So I still considered him to be my father. But when I was 13 years old, he ended up committing suicide. Looking back, I see how traumatic that was for me and how that kind of shaped my identity.”

Krimes, who was a talented artist from a young age, soon started dealing drugs at parties and developing a police record. It carried on through his college years.

“I would do my work, and then I would go out and live this kind of second life,” he said.

Krimes studied studio art at Millersville University and his future was looking bright. But by the time he graduated, it was too late.

“I got caught with roughly 140 grams of powder cocaine,” said Krimes, “and when they arrested me, they asked me to cooperate, and I kept refusing. I’m going to take responsibility for myself and that’s it.”

Art was his refuge in prison.

“I started creating work as a way to transcend all these negative things that are going on around me,” Krimes said of his early days in prison. “And what that actually did — it drew people closer to me.”

Creating techniques for survival, art

He eventually started teaching art classes to his fellow inmates. And he slowly developed a method of transferring images from the New York Times to prison sheets using a spoon and hair gel – materials he could easily acquire. He then began work on what would become “Apokaluptein.”

After each panel was finished, he would immediately mail it to his girlfriend back home so the material wouldn’t be confiscated.

“Making that work was a way to also transfer myself out of the prison system,” he said. “I mean, you really get lost in the work. It’s something where I feel like the piece is a part of me.”

With good behavior, Krimes served five years of a nearly six-year sentence. He had a job waiting for him with the Mural Arts Program in Philadelphia. And, then just a few months after his release, the Zimmerli Museum at Rutgers University caught wind of his work.

Curator Donna Gustafson said she was immediately moved by the work’s depiction of time.

“It’s really kind of a visual time,” she said. “How is time lived, and how is time remembered? And what is it like to experience time in a place all by yourself where you don’t really have access to the usual mechanisms of time and sociability and day and night?”

Krimes was incarcerated just 100 miles south of the Zimmerli, in New Jersey’s Cumberland County.

“He spent a whole day installing the show,” Gustafson said. “And when he finished, we all said, ‘What do you think?’ He said, ‘I feel like I won.'”

“It’s one of the most empowering experiences I’ve ever had,” said Krimes. “There’s something really nice about having my first solo exhibition in the same state that had me in prison.

“All this happened within the first year of coming home, so I’m just trying to get re-established with family and friends.”

Krimes’ future is looking bright with some of his work heading to display in Paris early next year. But he said he’s really just focused on the thing that saved him: Making art every day.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.