Mobile cancer screening funding in jeopardy

Hundreds of Delaware women who receive services on the state-funded Mobile Health Screening Van may have to seek other providers if the state decides to cut its funding.

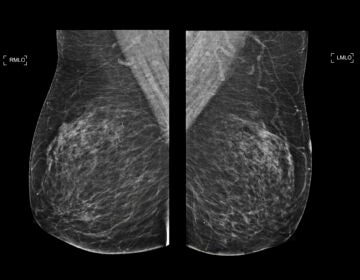

(Courtesy of CM Baker)

For 20 years, the Women’s Mobile Health Screening Van has traveled throughout Delaware to provide mammograms to under-served and uninsured women.

But the hundreds of women who receive services on the van may have to seek other providers if the state decides to cut its funding.

Gov. John Carney’s recommended budget for fiscal year 2019 proposes eliminating the van, which would save the state close to $277,000.

The van is funded by the state’s Division of Public Health, which contracts with the Delaware Breast Cancer Coalition for its operation, in partnership with Beebe Medical Center.

Members of the coalition say they were caught off guard by the news, because the state funded a new van two years ago and contracted with them to add more types of screenings to its services.

“We intend to advocate on behalf of the van and the work it’s doing,” said Vicky Cooke, the organization’s consultant and former executive director.

The Women’s Mobile Health Screening Van began operating in 1992 to address accessibility and affordability for the uninsured population.

No woman is ever turned away from a mammogram on the van, which travels to various locations in the state, mostly to areas with the greatest need.

The goal is to get more women screened, as early detection improves a patient’s chance of survival.

Between 2006 and 2010, female breast cancer diagnoses in Delaware were 127.1 per 100,000 — above the national rate. While diagnoses among white women decreased in that period, diagnoses among African-American women increased 4.6 percent.

Delaware’s breast cancer mortality rate was 22.5 per 100,000 during those years. However, it was still a 29 percent total decline from previous years — and a 40.7 percent decline among African-American women.

In 2016, the coalition received a new van, and hired a nurse practitioner to add cervical, glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol screenings to its services.

The coalition said last year it screened 1,005 individuals for mammograms, and an additional 300 individuals for its other screenings. The organization said those numbers don’t include outreach numbers off the van.

The state provided different numbers for women served by the van. The Division of Public Health numbers show the van served 1,013 women, providing mammograms to 971 women.

Regardless of the exact number of women served, providing these services is somewhat costly. The organization said its actual budget for the contract is $398,227, with $291,247 used for salaries and the remainder for its contractor fee, operating costs, and marketing. The budget has increased since hiring a nurse practitioner for the additional screenings.

Seven staff members — including a program coordinator, van driver, data analyst, mammography technician, nurse practitioner, and bilingual outreach member — would lose their job if the van stopped operating.

Christina Richter, vice president of development, argues the van drives down overall costs for the state, as more women have access to preventive care.

“I think a mobile van plays really nicely into the movement of population health. We’re really trying to work with the acute settings, the hospitals, to look at readmission rates. And the beauty of a mobile van is we can take it into communities struggling with transportation needs, cultural barriers. We have bilingual staff,” she said.

“So, I think there’s value in the van in the fact it’s driving down some health care costs, overall emergency room visits. We can have those conversations with women on the van while they’re with us. That’s the beauty of having the nurse practitioners. It’s really a holistic look at women’s health.”

However, Division of Public Health director Karyl Rattay said the need for the van is not as great as it was 20 years ago, as accessibility is no longer a significant barrier.

“Now there are more standing/fixed sites where women can get screening — including at nights and on weekends,” she said. “Additionally, there are Nurse Navigators in place throughout Delaware to assist patients with scheduling appointments and coordinating transportation if needed. Transportation services have also expanded statewide through DART bus services and ride-sharing programs.”

In addition, Rattay said affordability is less of an issue today, due to the state’s Screening for Life program, the enacting of the Affordable Care Act, and the expansion of Medicaid.

“Breast screening is now considered a preventive health screening and most insurance plans are now required to pay for screenings without copays. With improved access to coverage through the Affordable Care Act, only about 5 percent of the population served by the van today is uninsured,” Rattay said.

“With coverage in Delaware now so widespread, it is important for the state to examine areas where we may have gaps in care and determine if dollars should be redirected to bolster these areas. DPH is discussing approaches with the Delaware Breast Cancer Coalition to ensure women who need services have access to them in the most efficient way possible.”

Cooke points out that many of the insured women who receive screenings on the van are insured, because coalition staff navigated them to the ACA’s marketplace.

“If somebody just called a standing mammography site and didn’t have insurance and didn’t have a medical home, I doubt the scheduler would be able to take the time to navigate that person through the system. Therefore, the person probably wouldn’t get screened,” she said.

Richter said even if someone is insured through the ACA, they often can’t afford the premiums or deductibles.

“Even though people are in the marketplace, they still find they’re making choices every day whether to have food or go to their private care provider. People are making these decisions. They often don’t go to see their doctors,” she said.

Cathy Holloway, vice president of mission delivery, said women continue to face barriers to health care.

“Even women with insurance, if they’re hourly wage workers, they may not be able to take time off from work without getting docked pay and not being able to pay their bills. So many women hesitate to take half a day or a full day off work to get screened,” she said.

Coalition members say the wraparound services the van provides, such as healthcare navigation, referring women diagnosed with cancer to support systems, outreach and education in communities and bilingual communication, make a significant difference to patient’s healthcare.

“Often when you go to a medical community you don’t often get that [respect], so you go back into the shadows and you don’t get medical care,” Richter said. “So, this isn’t about mammography, it’s about getting the best medical care you can.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.