Marrying art with scientific inquiry opened new windows on the world

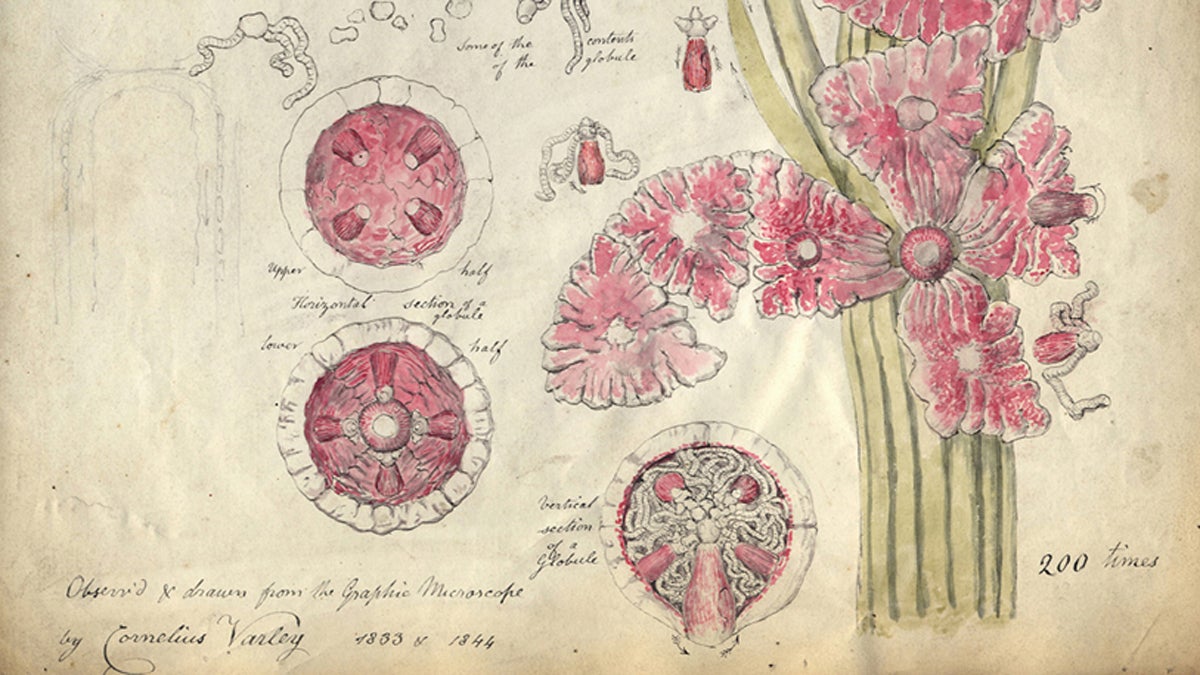

"Chara vulgaris," watercolor by Cornelius Varley, 1833 and 1844 (Courtesy of APS Collection)

Primarily known as a British artist, Cornelius Varley was an equally accomplished inventor, creating drawing instruments to bring fine details of the natural world into focus. The results of the interaction between Varley’s artistic sensibility and scientific curiosity are on view through December in “Through the Looking Lens,” an exhibit at Philadelphia’s American Philosophical Society Museum.

“Look both ways. For the road to a knowledge of the stars leads through the atom; and important knowledge of the atom has been reached through the stars.”— Arthur Eddington, British astrophysicist

Cornelius Varley (1781-1873) was looking both ways long before these words were uttered. Primarily known as a British artist, Varley was an equally accomplished inventor, creating drawing instruments to bring fine details of the natural world into focus. The results of the interaction between Varley’s artistic sensibility and scientific curiosity are on view through December in “Through the Looking Lens,” an exhibit at Philadelphia’s American Philosophical Society Museum.

At age 12, after his father’s death, Varley was apprenticed to his uncle Samuel, a maker of scientific instruments. Samuel encouraged the child’s interest in the drills, lathes, and soldering irons of his trade, and in what could be done with them.

Varley later wrote, “With him I began to see the wonders of science, air pumps, electrifying machines, telescopes and microscopes and became eager to make lenses.” He quickly progressed to jewelling watches, and soon applied his skills beyond timepieces.

If it doesn’t exist, invent it

Varley once thought he would paint for a living. Having tested state-of-the-art drawing tools, the camera obscura and camera lucida, he concluded that he needed a more portable, easier-to-use instrument. In 1809 he designed one.

The Patent Graphic Telescope (PGT) was fitted with microscopic and telescopic lenses, enabling Varley to see worlds as fanciful as Alice’s Wonderland, from Welsh cliffs to algae dipped from a pond. He devised a folding stand, to provide a steady surface for sketching almost anywhere. Employing a mirror, the instrument splits the view between subject and drawing surface, enabling the user to outline, and to enlarge or reduce, the image. Drawings produced with the PGT offered photographic accuracy 30 years before the invention of the first camera, in 1839.

After patenting the PGT in 1811, hoping it could be manufactured, Varley found tradesmen reluctant. “It would have required them to learn more of their own business, which settled tradesmen seldom like,” he wrote. “So I had to accumulate tools and make them myself.”

One of the few remaining PGTs handcrafted by Varley, the centerpiece of the APS exhibit, is owned by the Franklin Institute. Surrounding it are his pencil sketches, vivid watercolors, published drawings, and handwritten narrative. Visitors can also try their hands at modern recreations of the camera obscura, camera lucida, and PGT.

Showcasing 21st century inventors

If Varley visited the APS exhibit of his work, 200 years on, he’d meet people much like himself. In May, members of Hive 76, which describes itself as a community of “makers and crafters,” showcased examples of their present-day inquiries, such as a 3-D printer.

“Cornelius Varley was an inventor, tinkerer, artist, and scientist,” says Jordan Miller, Hive 76 board member and assistant professor of bioengineering at Rice University. “Hive 76 is a modern-day group following very much in the same ethos as Varley. While each project has different goals — some whimsical, some artistic, some scientific — each project stimulates the viewer to think in new ways. This thread was key to Varley’s works.”

Earlier this month, an updated, more portable version of the camera lucida, the neolucida, was demonstrated by its inventor, Pablo Garcia, an assistant professor of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Were he alive today and living in Philadelphia, the 19th century British inventor might well be a Hive 76 member, sharing Center City workspace and collaborating on projects that include an acoustic camera, to illuminate the world through sound; a do-it-yourself hydrophone, an underwater listening device made from household items; or a display screen made of bacterial cellulose, an item that appears quite similar to Varley’s depictions of algae.

Preserving the inventive spark

Consistent with his ties to art and science, Varley was involved in the founding of the Society of Painters in Watercolors (1804) and the Microscopal Society of London (1839). As a member of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, he worked to advance useful inventions, discoveries and improvements, a purpose not so different from that of the APS, founded in 1743 by Benjamin Franklin to document and foster the study of the natural world.

As represented by more than 100 documents, drawings, and objects on display, the innovative impulse that inspired Cornelius Varley is the same impetus that extends back through Franklin and forward through modern day inventors. In every age, there are people who want to do what has only been imagined, who feed on one another’s creativity and crash through boundaries to find the key insight, the sought-after improvement, the necessary solution. Like Varley, whose curiosity splashed beyond watches and portraits into botany, meteorology, physics and anatomy, they pursue what hasn’t been seen … yet.

—

Correction: In a previous version of this story, Jordan Miller was incorrectly identified as Jacob Miller.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.