SBN report tackles PWD’s long-term gain vs. short-term pain

March 10, 2010

By Thomas J. Walsh

For PlanPhilly

Hoping to leverage the Philadelphia Water Department’s ambitious new $1.6 billion, 20-year stormwater management plan, the Sustainable Business Network of Greater Philadelphia (SBN) will issue a report Wednesday on the financial challenges facing private property owners and developers in the coming years.

The paper is “groundbreaking,” according to Howard Neukrug, director of the PWD’s Office of Watersheds and a nationally known stormwater management specialist.

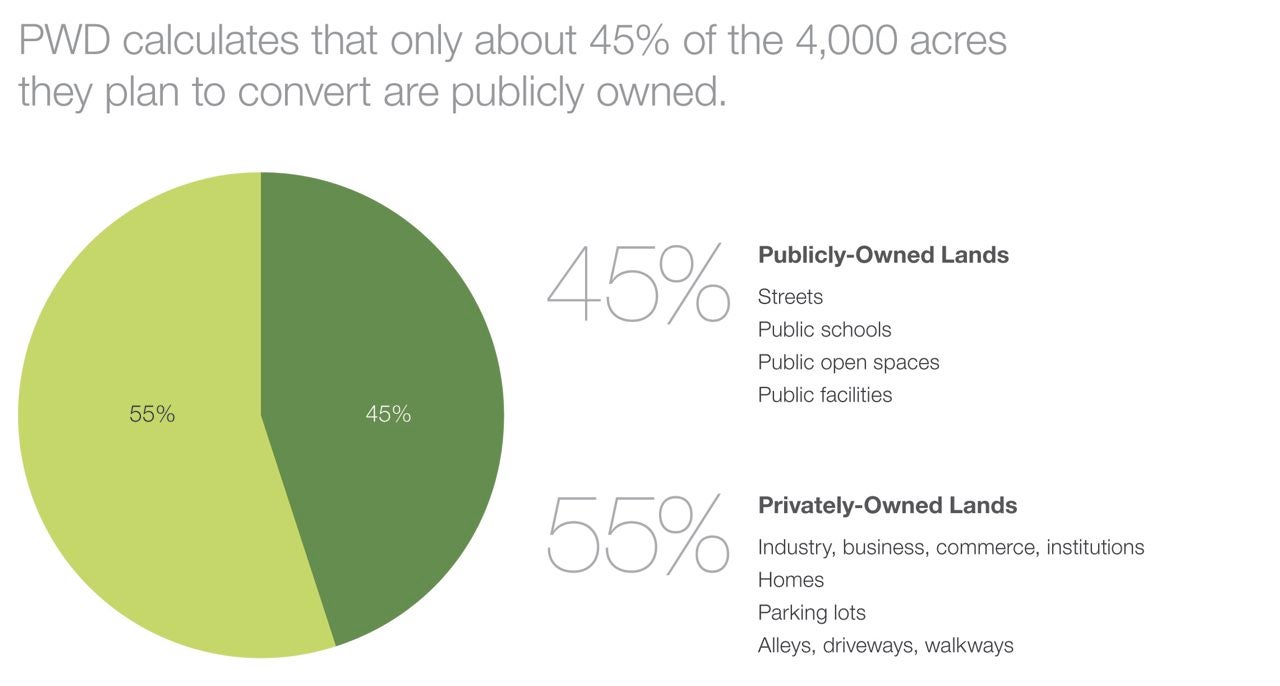

Meant to serve as a “primer” for non-residential private landowners – who control about 55 percent of the city’s 4,000 acres identified by the city as covered by impervious surfaces – the report is called “Gray to Green: Jumpstarting Private Investment in Green Stormwater Infrastructure.”

The report directly addresses the PWD’s “Green City, Clean Waters” plan, released six months ago, which will use a “land-water-infrastructure approach” for a new program that will manage the region’s stormwater runoff in a way that reduces reliance on the construction of additional underground infrastructure. Starting this year, it will include a new water and stormwater fee and billing structure for property owners, measuring lot sizes and factoring in impervious surfaces – effectively increasing bills for places with large roofs or sprawling parking lots (or both).

The private sector’s participation in the PWD plan faces “significant barriers,” the SBN reports.

“For the ‘Green City, Clean Waters’ plan to succeed, the city will need a critical mass of installations – making private participation and investment imperative,” wrote Sarah Francis, the policy fellow at SBN who authored the report. Francis recently accepted a position as a consultant to the Department of Energy in Washington, D.C.

“It is in the best interest of the city to ease this transition, and clearly communicate financing and best practices to companies considering new projects to reduce their impervious surface area.”

By installing new porous surfaces, cisterns and other rain collection units, green roofs, retention basins, and other methods of decreasing runoff, companies can offset or decrease their bills.

“I think it’s a tremendous report,” said Neukrug. “I was just thrilled when I read it, how well it does in describing the issues that are confronting us today, and beginning to look at what some of the solutions may be.”

“The bind that property owners face is cost,” said Kate Houstoun, director of green economy initiatives for SBN, in an interview with PlanPhilly on Monday.

“The city government can only take it so far to incentivize green stormwater infrastructure,” agreed Francis, who said that the PWD would need to partner more directly with private developers and business owners. Because the Water Department cannot serve as a financing conduit, “probably the [quasi-public] Philadelphia Industrial Development Corp. (PIDC) is the most obvious partner” if those barriers to private participation are to be overcome, Houstoun said.

In other words, before Philadelphia can get to Mayor Michael Nutter’s goal of being the “greenest city in America,” it is going to have to do a good deal of mucking around in the gray areas – in finance as well as infrastructure – first.

That includes how the new water plan is laid out in the new city zoning code, now being re-written by the Zoning Code Commission (ZCC) and its hired consultants, and the ultimate new comprehensive city plan that will come along in its wake.

“Everybody has to have buy-in,” Francis said, “across the board in city government.”

Recycling carrots. sticks

Eva Gladstein, executive director of the ZCC, said that she is meeting with the PWD next week, for the second time, to talk about the Clean Waters plan and ways in which the zoning code can be supportive of it.

Regarding any means of efficiently greening the city, she said the new fee structure would probably be more expeditious than the long-term effects of the new zoning code.

“We can look at open space requirements and the degree to which pervious surfaces compare with impervious surfaces – the current code really doesn’t distinguish between the two,” Gladstein said. “But my guess is that there will have to be multiple strategies.

“The zoning code can’t make anything happen. The zoning code can create a framework and encourage certain kinds of development, but very often the economic strategy is either through relief or through fees. Here, both the carrot and the stick are more direct ways to accomplish the goals.”

The new code will also be supportive of the PWD plan because it will require more landscaping than the current one (for city-owned as well as privately owned property and buildings), Gladstein added.

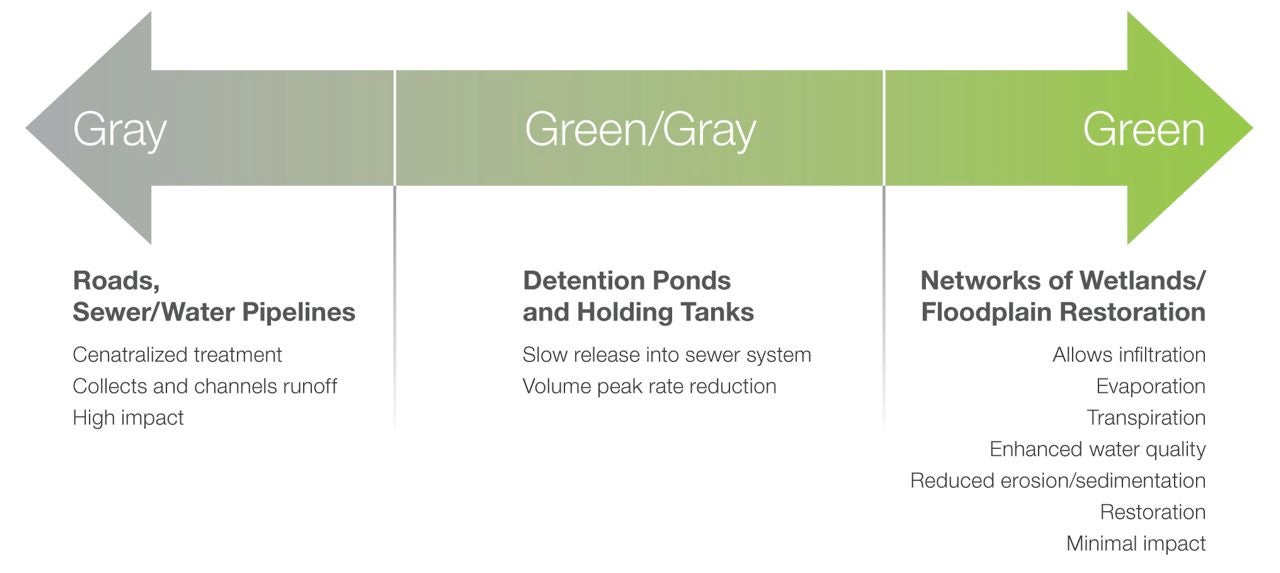

The “gray” in the title of the report refers to old, single-purpose, man-made systems such as highways, or sewer and water treatment systems that are often “high-impact” and costly. “Green” stormwater infrastructure mimics natural systems via tree planting, the installation of green roofs and infiltration basins, but also small things such as planter boxes or rain barrels (such barrels are currently illegal within the city, but not something that is enforced).

“The new regulations are going to be a forceful factor,” said Christine Knapp, director of outreach at Citizens for Pennsylvania’s Future (PennFuture). “That’s where having some systems set up, and financial resources made available, would be really helpful to the private sector.”

Possible fallout

Craig Schelter, former head of the City Planning Commission and an economic development executive who now represents a consortium of private city landowners, said the issue is “clearly something we’re keeping an eye on.” But he added that Neukrug’s approach is incremental and “cutting-edge” – the preferred alternative to saddling private landowners with the massive costs of replacing infrastructure that is becoming obsolete.

“The concern is that no one knows quite how the remediation parts of this work, or where the mitigation measures work,” Schelter said. “I know at the Navy Yard whenever they have a project now, where there’s a parking requirement, they try to incorporate bio-swales and things like that into the design to minimize the effects of a surface parking lot. But … just anecdotally, I know there’s been something of a shock as to how much bills could go up.”

Francis wrote that PWD is still ironing out the details – and problems – within several programs.

One is that stormwater management regulations require development projects disturbing more than 15,000 square feet of earth to manage the first inch of rainfall for impervious areas directly connected to the sewer system. “PWD is currently considering lowering the threshold to 5,000 square feet, dramatically improving the environmental impact, but affecting many more property owners,” she wrote.

Another is how to dole out stormwater management system credits, along with “devising additional incentives, such as expedited permitting, for using green techniques for managing stormwater.

“As of now, it would be permissible to use gray structures, like underground holding tanks, which only allow for slow release of stormwater into the sewer system, in order to qualify for the [stormwater management] credit,” Francis wrote. “While this new billing structure does the City service by more accurately capturing the burden that stormwater places on our water system, as well as creating incentives for individuals to take responsibility for stormwater on their site, it also has the potential to hurt key non-residential landowners.”

As Schelter and others previously noted, the new billing system could hike water bills “exponentially.” And while everyone wants to go green, “regulations alone have the potential to drive off development,” Francis notes. Therefore, the City and PWD need carrots that are as sweet as its sticks are hard.

“Additional financing structures, akin to what is being used in the energy efficiency industry, will be required to incentivize the conversion to green stormwater infrastructure by negating the upfront capital costs these conversions will place on landowners,” the report states.

‘All new thoughts’

The “Gray to Green” report on private investment for stormwater management is SBN’s fourth for its “Emerging Industries Project.” In partnership with the Green Economy Task Force, co-led by SBN Executive Director Leanne Krueger-Braneky, the first three were analyses on redeveloping local sustainable manufacturing infrastructure; developing construction and demolition waste recovery; and energy efficiency and retrofit strategies.

Case studies included in the “Gray to Green” report include integrative planning and water management in Portland; “on-bill financing” through residential loans at the Manitoba Hydro company in Canada; and the Smart Energy Initiative of Southeastern Pennsylvania, an example of effective industry partnerships that PWD might explore further.

Though PWD is clearly a city leader and a national model for “triple bottom line” benefits going forward, “every factor involved in successful implementation [of the Green City, Clean Waters plan] will not and cannot fall on PWD’s shoulders alone,” wrote Francis.

Well-structured tax policies and regulations are important, but “other systems that spur and attract private investment, such as innovative financing mechanisms, business networking, and workforce development programs, are needed,” she says.

“Only with such a systems-based approach can Philadelphia reinvent itself as the greenest city in America.”

Neukrug said SBN’s recommendations for financing mechanisms are excellent, and will be seriously considered.

“This whole concept of ‘green stormwater infrastructure service companies’ (GISCs) is very intriguing,” he said. “I don’t know if something would actually happen with this, or if the economics of it could occur. But just beginning to think in different ways of how public and private landowners can start to re-think how to conserve rainwater on their properties and reduce their bills is a tremendous double win.”

GISCs would do for stormwater infrastructure what energy service companies (ESCOs) have done for energy conservation retrofits, the thinking goes. ESCOs make possible the installation of performance-based energy efficiency projects via financing, installation and maintenance services for equipment, while absorbing all the financial risk. Costs associated with any given project facilitated by an ESCO are folded into the company’s compensation contract and then repaid over time by the customer – with the post-installation savings.

“If this model were applied to the green stormwater infrastructure industry, it could reduce barriers of scale and capital for developers,” the report states.

“It’s certainly something that is working on the energy side,” Neukrug said.

“To start thinking about the solutions to rainwater, and how they relate to drinking water, and how does that relate to conservation of energy – and recognizing that they all have some commonality – these are all new thoughts,” Neukrug said of the SBN report.

“I haven’t seen that kind of suggestion anywhere else. I don’t want to overstate the potential for it to be our solution, but it is wonderful that people are so quickly beginning to think about the different means of exploring the environmental problems we have here in Philadelphia, and creative ways of solving them.”

Contact the reporter at thomaswalsh1@gmail.com.

ON THE WEB:

Full report here: see PDF attachment

Green City, Clean Waters report: http://www.phillywatersheds.org/ltcpu/LTCPU_Summary_HiRes.pdf

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.